National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

REFERENCE MANUAL 41: WILDERNESS STEWARDSHIP

NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide

Table of Contents

Re

commendation and Approval ……………………………………………………………….…… 2

Ac

knowledgments ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 3

In

troduction ……………...…………………………………………………………………….………. 5

Founda

tional Information ………………………………………………………………………….… 6

Wilderness Character Monitoring in the National Wilderness Preservation System …… 7

Wilderness Character Monitoring in the National Park Service (NPS) …………….......... 9

The Wilderness Character Monitoring Process ……………….…………………..…….... 14

Wi

lderness Character Monitoring by Quality

Untrammeled Quality …………………………………………………………………….…... 27

Natural Quality ……………………………………………………………………………..…. 29

Undeveloped Quality ………………………………………………………………….….….. 33

Solitude or Primitive and Unconfined Quality ………………………………………..……. 36

Other Features of Value Quality ………………………………………………………..…... 42

Re

ferences ……………………………………………………………………………….…….…..…. 47

Ap

pendices

Appendix A: Law and NPS Policy Framework for Wilderness Character Monitoring … 48

Appendix B: NPS Modifications to Keeping It Wild 2 …………………………………….. 50

Appendix C: List of Supplemental Wilderness Character Monitoring Tools Linked in

This Guide …………………………………………………………………...… 54

Li

st of Tables and Figures

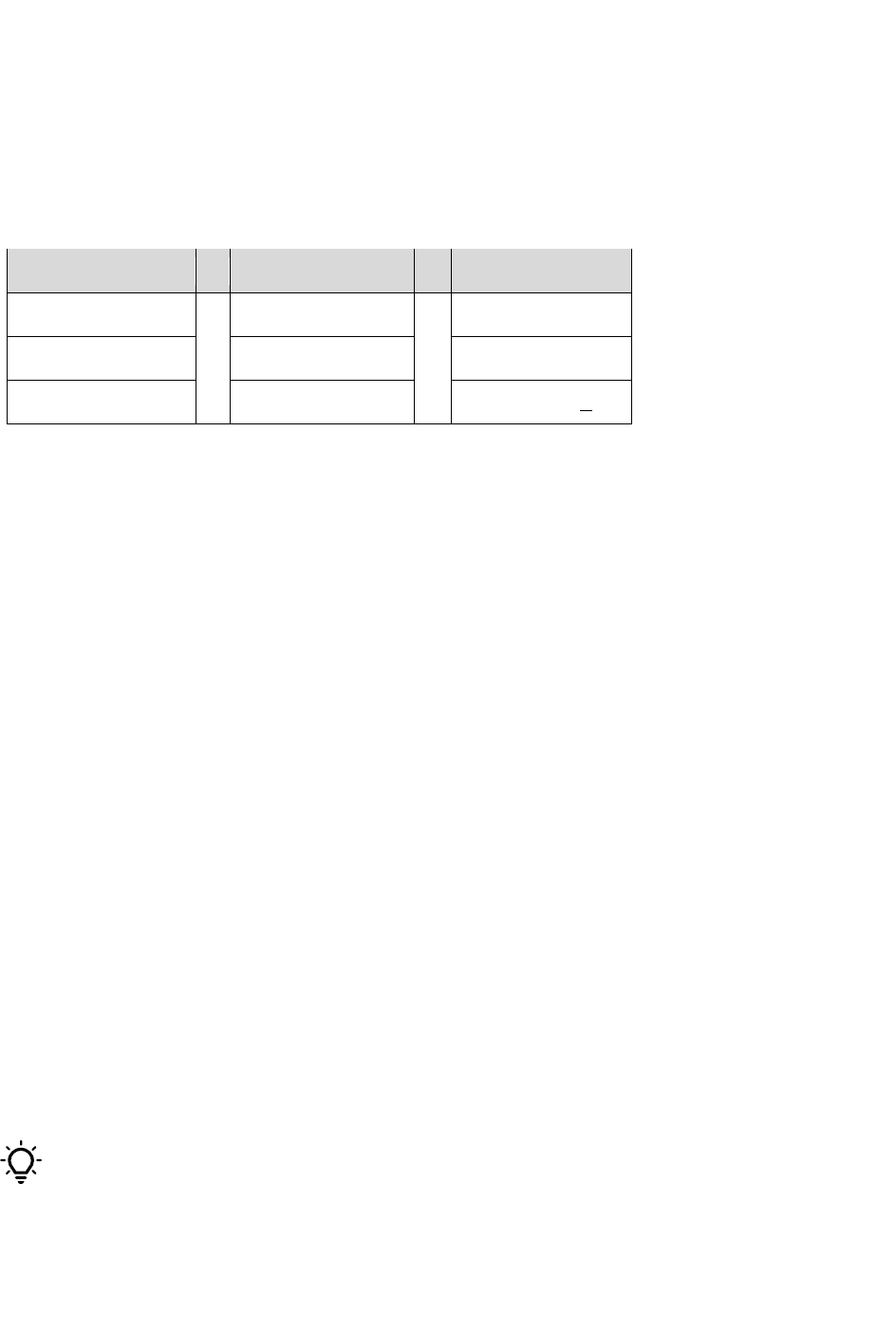

Table 1. Key interagency wilderness character monitoring concepts ……….…………... 8

Table 2. Wilderness character monitoring qualities, monitoring questions,

and indicators ……………………………………………………………………… 12

Table 3. Data adequacy rating table ………………………………………………...…….. 19

Table 4. NPS groups and their respective WCM roles …………………………………... 24

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Recommendation and Approval | Page 2

Recommendation and Approval for Inclusion in Reference Manual 41

Recommended

by

the WASO Wilderness Stewardship Division:

ROGER SEMLER

Digitally signed by

RO

GER SEMLER

Date: 2023.04.

26

06:15:47 -06'00'

Signature:

_____________________

_

Title: Program Manager, Wilderness Stewardship Division

Approval for inclusion for Reference Manual

41

by

WASO Visitor

and

Resource Protection

Directorate:

Di

gitally signed by JENNIFER

JENNIFER FLYNN FLYNN

Signature: Date: 2023.04.2

613

:46:21 -04'0

0'

Title: Associate Director, Visitor and Resource Protection Directorate

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Acknowledgements | Page 3

Acknowledgements

Ma

ny thanks to the following staff for their leadership in authoring this Guide:

Erin Drake, Communications and Outreach Specialist – WASO Wilderness Stewardship

Division

Nyssa Landres, Wilderness Coordinator – Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve

Kristin Pace, Wilderness Coordinator – Yukon-Charley Rivers and Gates of the Arctic National

Park and Preserve

Danguole Bockus, Ecologist – Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

Roger Semler, Program Manager – WASO Wilderness Stewardship Division

And thank you to the following subject matter experts who provided helpful insights:

Wendy Berhman, Planner – WASO Park Planning and Special Studies Program

Davyd Betchkal, Biologist – WASO Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division

Brad Blickhan, Wilderness Coordinator – Glacier National Park

Jim Cheatham, Park Air and Visual Resource Specialist – WASO Air Resources Division

Eddie Childers, Wildlife Biologist – Badlands National Park

Blair Davenport, Regional Staff Curator – Interior Regions 8/9/10/12

Tim Devine, Training and Development Specialist – WASO Wilderness Stewardship Division

Joe DeVivo, Deputy Division Lead – WASO Inventory and Monitoring Division

Susan Dolan, Park Cultural Landscapes Program Manager – WASO Cultural Resources

Partnerships and Science Directorate

Greg Eckert, Restoration Ecologist – WASO Biological

Resources Divis

ion

Heather Eggleston, Program Manager – WASO National Natural Landmarks Program

Kirstie Haertel, Archaeology and Museum Program Manager – Interior Regions 8/9/10/12

Terri Hogan, Invasive Plant Program Lead – WASO Biological Resources Division

Jason Kenworthy, Geologist – WASO Geological Resources Division

Mark Kinzer, Regional Wilderness Coordinator – Interior Region 2

Laura Kirn, Cultural Resources Team Lead – Channel Islands National Park

Al Kirschbaum, GIS and Remote Sensing Specialist – Great Lakes Inventory and Monitoring

Network

Adrienne Lindholm, Regional Wilderness Program Manager – Interior Region 11

Lori Makarick, Landscape Restoration and Adaptation Branch Manager – WASO Biological

Resources Division

Liz Matthews, Inventory and Monitoring Program Manager – National Capital Area

Jillian McKenna, Wilderness Data Steward – Glacier National Park

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Acknowledgements | Page 4

Mike Medrano, Resource Stewardship and Science Division Manager – Guadalupe Mountains

National Park

Jack Oelfke, Retired – North Cascades National Park

Ashley Pipkin, Biologist – WASO Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division

Rebecca Port, Geologist – WASO Geological Resources Division

Gregor Schuurman, Ecologist – WASO Climate Change Response Program

Ruth Scott, Wilderness Coordinator – Olympic National Park

Ksienya Taylor, Natural Resource Specialist – WASO Air Resources Division

Jay Theuer, Cultural Resource Program Manager – Joshua Tree National Park

Dave Trevino, Wildlife Biologist – WASO Biological Resources Division

Dean Tucker, Natural Resource Specialist – WASO Water Resources Division

Dan van der Elst, Wilderness District Ranger – Mount Rainier National Park

Rose Verbos, Planner – Denver Service Center Planning Division

PJ Walker, Wilderness Coordinator – Everglades National Park

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Introduction | Page 5

Introduction

Pur

pose of the National Park Service Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide

The purpose of this Guide is to provide national guidance on how to monitor and assess trends

in wilderness character for National Park Service (NPS) wilderness areas. This Guide supports

the NPS policy requirement that every wilderness park “will conduct a wilderness character

assessment, which includes identifying what should be measured, establishing baseline data,

and conducting ongoing monitoring of trends… Once a baseline is established, tracking change

and reporting on the trend in wilderness character should generally occur every five years”

(Director’s Order 41, Section 6.2 Wilderness Character).

This Guide applies to all areas in the NPS that have a statutory mandate and/or policy

requirement to preserve the wilderness character. See the “Wilderness in the NPS” section to

learn about NPS categories of wilderness.

Primary users of this Guide include wilderness managers, interdisciplinary park program

managers, and other field-level park staff who implement wilderness character monitoring

(WCM). National and regional NPS programs and partners that support parks in monitoring

efforts are also addressed here.

How This Guide is Organized

This Guide has three main parts

1

:

1. Foundational information: This section describes overarching WCM information for the

interagency National Wilderness Preservation System, the primary purpose for WCM in

the NPS, the NPS national framework for developing baseline assessments, the scope

of NPS lands to which WCM applies, and NPS roles and responsibilities for

implementing WCM.

2. WCM by quality: This section describes important information about each tangible

quality of wilderness character and its related WCM framework components. Example

measures and measure idea templates are listed for each quality.

3. Appendices: The appendices provide relevant background and context for WCM to

supplement information in this Guide.

To emphasize content that readers may want to revisit, three icons are used throughout this

Guide:

List of steps or concepts for reference.

Availability of a document template for use.

Ideas or questions to consider before advancing.

1

Many of the links referenced in this Guide connect to documents that only DOI employees can view.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 6

Foundational Information

What is Wilderness Character Monitoring and Why Do It?

The statutory mandate of the Wilderness Act is to preserve wilderness character. This

affirmative legal obligation applies to all designated wilderness areas across the entire National

Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS), including all NPS wilderness areas. This is affirmed

by NPS Management Policies 2006, Chapter 6 which states that management of these areas

will “preserve their wilderness character, and… the purpose of wilderness in the national parks

includes preservation of wilderness character…”

To ensure that wilderness character is preserved, it must first be defined. The Wilderness Act

does not define wilderness character. As such, a federal interagency wilderness team

collaborated to define wilderness character based on references and language from the

Wilderness Act (Landres et al. 2015):

Wilderness character is a holistic concept based on the interaction of (1) biophysical

environments primarily free from modern human manipulation and impact, (2) personal

experiences in natural environments relatively free from the encumbrances and signs of modern

society, and (3) symbolic meanings of humility, restraint, and interdependence that inspire

human connection with nature. Taken together, these tangible and intangible values define

wilderness character and distinguish wilderness from all other lands.

Given the breadth of this holistic concept, WCM focuses on a specific subset of tangible

qualities of wilderness character that are derived from the Definition of Wilderness, Section 2(c)

of the Wilderness Act:

1. Natural Quality

2. Untrammeled Quality

3. Undeveloped Quality

4. Solitude or Primitive and Unconfined Recreation Quality

5. Other Features of Value Quality

Through the lens of the five tangible qualities, WCM equips managers with a framework to

consider and steward changes that meaningfully affect the condition and trend of wilderness

character. Parks can use WCM information to assess the effects of past management decisions

on wilderness character and to inform decisions about future actions. WCM is distinct from other

forms of monitoring because monitoring results must be translated into a conclusion of impact

on wilderness character. This translation requires sound professional judgment and thoughtful

insight by managers. Subjectivity is a known element of WCM, as impacts to wilderness

character are nuanced, complex, highly variable, and necessitate professional judgment in

translating observed changes into management implications for wilderness character.

Simultaneously, the WCM framework is designed to counterbalance aspects of this subjectivity

by making processes and analyses more transparent and consistent.

Monitoring by itself does not provide guidance for what to do if trends in wilderness character

are declining; instead, monitoring can signal the need for follow-up actions or decisions and can

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 7

clarify the tradeoffs associated with actions or decisions. The results from WCM can also

highlight qualities or aspects of wilderness stewardship that are changing in condition and may

need to be addressed by park management. Monitoring informs and helps improve wilderness

stewardship by encouraging management accountability for the central mandate of the

Wilderness Act - to preserve the wilderness character of every wilderness area for present and

future generations.

WILDERNESS CHARACTER MONITORING IN THE NATIONAL WILDERNESS

PRESERVATION SYSTEM

Interagency and Agency-Specific Wilderness Character Monitoring Guidance

The NWPS includes wilderness areas managed by the NPS, Bureau of Land Management

(BLM), US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and US Forest Service (USFS). This Guide is

related to, and builds on, existing WCM guidance for the NWPS and the NPS.

Keeping It Wild 2: An Updated Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character

Across the National Wilderness Preservation System (KIW2) (2015)

KIW2 is the interagency monitoring strategy and framework of qualities, monitoring questions,

and indicators used in WCM. KIW2 updated the interagency framework of WCM and replaced

the original interagency Keeping It Wild (2008). KIW2 was endorsed in 2016 by the Interagency

Wilderness Policy Council and subsequently approved for inclusion in NPS Reference Manual

41: Wilderness Stewardship. The WCM framework defined in KIW2 provides the organizational

structure of this Guide. However, the NPS has made some agency-specific modifications to this

framework for NPS wilderness areas.

See each quality’s chapter and Appendix B in this Guide for additional details on

modifications to guidance described in KIW2. These modifications reflect lessons learned

since KIW2's release in 2016 regarding what is most useful to parks for WCM purposes. In

cases where guidance differs between KIW2 and this Guide, NPS users should refer to this

Guide.

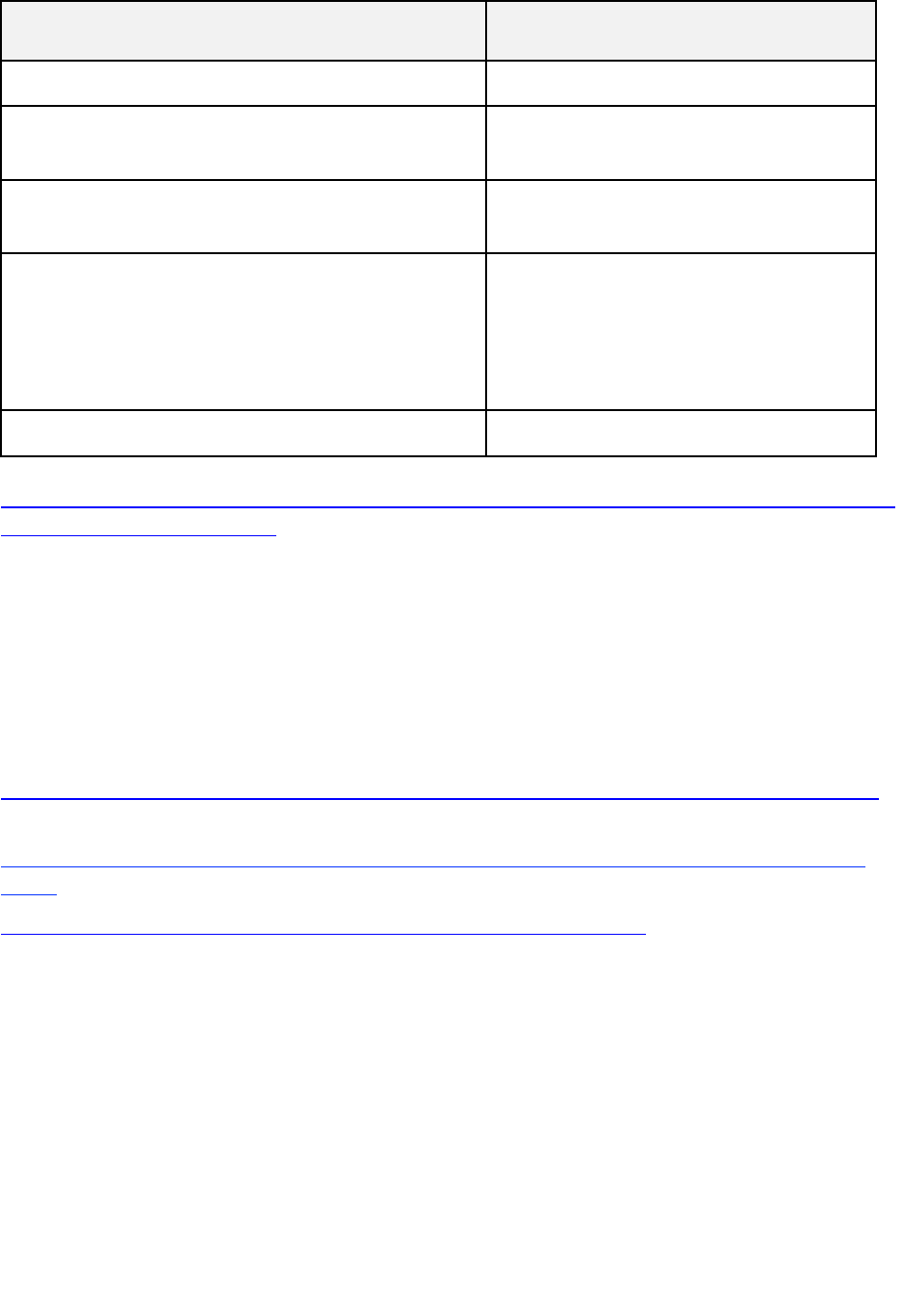

KIW2 includes extensive descriptions of important WCM concepts. For brevity, these concepts

are not reiterated in this Guide. Instead, they are incorporated by reference (Table 1). This

approach in no way diminishes the importance or relevance of these concepts; they are

foundational to understanding the conceptual framework of WCM.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 8

Table 1. Key interagency WCM concepts described in Keeping It Wild 2

Interagency WCM Concept Keeping It Wild 2 Location

Assessing trend Pages 17-19, 24-29

Shared management responsibility with another

agency (BLM, USFWS, USFS)

Page 23

Detailed description of the five tangible qualities

of wilderness character

Pages 33-60

Detailed description of hierarchical framework

This Guide does offer flexibility for some

components of the KIW2 ‘required’ WCM

framework.

Pages 4,17-18

What is a trammeling action? Pages 101-106

Keeping It Wild in the NPS: A User Guide to Integrate Wilderness Character into Park Planning,

Management, and Monitoring (2014)

Keeping It Wild in the NPS is agency-specific guidance on how to integrate wilderness character

into park management. This includes introducing integral WCM-related items like the wilderness

character building blocks (including a wilderness character narrative and baseline assessment).

Because Keeping it Wild in the NPS was developed a year prior to KIW2, it does not reflect the

updated and revised WCM framework from KIW2 (and relevant updates in this Guide), but its

guidance for integrating wilderness character into overall park planning, management, and

monitoring is still relevant.

Survey Protocol Framework for Wilderness Character Monitoring on National Wildlife Refuges

(2018)

Measuring Attributes of Wilderness Character: Bureau of Land Management Implementation

Guide (2020)

US Forest Service Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (2020)

These three documents are the functional equivalents of this Guide for the USFWS, BLM, and

USFS. Portions of this Guide are modified from these documents to promote interagency

consistency where feasible.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 9

WILDERNESS CHARACTER MONITORING IN THE NATIONAL PARK

SERVICE

Wilderness in the NPS

Over 44 million acres of NPS lands are designated as wilderness by Congress. An additional

26+ million acres of lands are eligible, proposed, recommended, and potential wilderness. In

total, over 80 percent of the entire National Park System is managed as wilderness.

The mandate to preserve wilderness character applies to all categories of wilderness per NPS

policy. NPS Management Policies 2006, Chapter 6 states “[f]or the purposes of applying these

policies, the term ‘wilderness’ will include the categories of eligible, study, proposed,

recommended and designated wilderness.” Accordingly, WCM will be conducted for all NPS

categories of wilderness.

NPS Primary Purpose of Wilderness Character Monitoring

NPS WCM aims to principally support park-specific wilderness character needs. The primary

purpose of WCM in the NPS is to help parks consider and steward changes that meaningfully

sustain or improve the condition and trend of the park’s wilderness character. This emphasis on

local relevance means that the strength of servicewide WCM functions (i.e., national condition

and trend assessments for wilderness character) may be diminished to achieve this place-

based purpose. This tradeoff is both recognized and accepted.

NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Definitions

The following terms are essential to the NPS WCM process. These

definitions are NPS-specific and may differ from another agency’s

interpretation of the term.

• Baseline measure value = the reported value (quantitative or

qualitative) for a measure from the ‘baseline measure year’.

This value is the reference/comparison point to assess the

‘trend’ in a specific measure over time, where the current

‘reported measure value’ is compared to the baseline measure

value.

• Baseline measure year = the earliest year data is available to

report a ‘baseline measure value’ for an individual measure.

• Change = an informal comparison of the state of wilderness

character for a ‘measure,’ ‘indicator,’ ‘monitoring question,’

‘wilderness character quality,’ or overall wilderness character.

Change is determined by comparing the ‘reported measure

value’ to the ‘baseline measure value’ for measures with fewer

than five data points informing the current ‘reported measure

value.’ Like ‘trend’, interpreting change should be informed by

the measure’s corresponding ‘threshold for meaningful change’ to help interpret the

comparison. Recognizing a ‘change’ in condition prompts managers to consider the

cause and effects of the change while awaiting enough data points to make official

‘trend’ conclusions.

WCM Terminology

Baseline measure value

Baseline measure year

Change

Indicator

Measure

Measure components

Modern

Monitoring

Monitoring question

Park

Reported measure value

Threshold for meaningful change

Trend

Wilderness character baseline

assessment

Wilderness Character Building

Blocks Report

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 10

• Indicator = distinct and important components under each ‘monitoring question’ within

the ‘WCM framework’. There is at least one standardized indicator for every ‘monitoring

question’. Each indicator selected will have at least one corresponding ‘measure.’

• Measure = specific elements under each ‘indicator’ within the ‘WCM framework’. Each

measure yields data that is collected to identify condition and assess ‘trend’ in the

‘indicator’. Measures are selected by the park.

• Measure components = Individual components of a ‘measure’ that provide the detailed

parameters to successfully implement and monitor the ‘measure.’ Each selected

‘measure’ must address and document all measure components in the ‘Wilderness

Character Building Blocks Report’. Measure components include measure title, context

and relevance, definitions, protocol, data sources, data adequacy, frequency, threshold

for meaningful change, and caveats and cautions.

• Modern = the time since the area was first managed to preserve wilderness character.

For most parks, this will be the year a wilderness eligibility assessment, or equivalent

documentation, was completed.

2

The use of modern helps managers determine the

scope of time to consider when assessing impacts to wilderness character and does not

negate the longstanding and ongoing relationships shared between people and lands

currently managed as wilderness.

• (Long-term) Monitoring = the recurring monitoring of measures according to protocol

described in a park’s ‘Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report’ (and subsequent

WCM framework modification protocol). Monitoring intervals will depend on measure-

specific protocol described in the report, occurring every five years at minimum.

• Monitoring question = questions that frame essential components of each tangible

‘wilderness character quality’ within the ‘WCM framework.’ Each standardized monitoring

question has multiple ‘indicators.’

• Park = local NPS unit responsible for managing a specific wilderness area.

• Reported measure value = the reported value for a measure that serves as a

comparison to the ‘baseline measure value’ to assess ‘trend’ in the measure. This value

is reported every five years and may be a composite of several years of data, depending

on the measure’s protocol.

• Threshold for meaningful change = a quantitative and/or qualitative set of parameters

that interpret change in the current ‘reported measure value’ compared to the ‘baseline

measure value’. This comparison distinguishes minor/reasonable change (within

identified thresholds) from meaningful change (exceeding the identified threshold, which

can be positive or negative). The outcome of this change is used to determine ‘trend’.

• Trend = a formal comparative assessment of the state of wilderness character for a

‘measure,’ ‘indicator,’ ‘monitoring question,’ ‘wilderness character quality’, or overall

wilderness character of the area. Trend is officially determined by comparing the current

2

This definition of modern considers the social, cultural, and ecological conditions that precipitated the

creation of the Wilderness Act. Concerns about the pace of industrialization (i.e., ‘expanding settlement

and growing mechanization’) inspired wilderness supporters to consider ways of protecting public lands

from these ‘modern’ impacts. The definition of ‘modern’ may be modified if agreement is reached by the

park’s interdisciplinary wilderness team, including representation from cultural resources and facilities. A

thoughtful rationale for a modified definition must be documented in the Wilderness Character Building

Blocks Report.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 11

‘reported measure value’ to the ‘baseline measure value’ if the current ‘reported

measure value’ includes a minimum of five data points. Trend references the measure’s

corresponding ‘threshold for meaningful change’ to help interpret the comparison and

conclude if the trend is improving, stable, or declining. Absent the availability of five data

points, ‘change’ (rather than trend) between current and baseline measure values can

still be discussed and documented.

• Wilderness character baseline assessment = the comprehensive representation of all

required ‘WCM framework’ components applicable to a specific park that establishes a

reference point for future ‘trend’ comparisons. This assessment is complete when all

selected measures have an identified ‘baseline measure year’ and ‘baseline measure

value’.

• Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report = a document that includes both the

wilderness basics and ‘wilderness character baseline assessment.’ For the wilderness

character baseline assessment building block, the report documents the comprehensive

‘WCM framework’, including all selected ‘measures’ and related protocols, and ‘baseline

measure values’ and ‘baseline measure years’. This report should note the ‘WCM

baseline year’ and serves as a reference for all ‘monitoring’.

• WCM baseline year = the first year that data are reported for all measures in a park’s

‘WCM framework’. At a minimum, this means that at least one measure is identified for

every required indicator and each of these measures has a ‘baseline measure value’.

• WCM framework = the combination of all monitoring components for wilderness

character, including ‘wilderness character qualities’, ‘monitoring questions’, ‘indicators’,

and ‘measures.’

• Wilderness character quality = the primary tangible attribute(s) of wilderness character

that links directly to the statutory language of the Wilderness Act. Commonly referred to

as “the qualities”, the same set of five qualities applies to all federal wilderness areas:

Natural, Untrammeled, Undeveloped, Solitude or Primitive and Unconfined Recreation,

and Other Features of Value. Within the ‘WCM framework,’ each quality has at least one

corresponding ‘monitoring question.’

National Framework for WCM

The national framework for WCM in the NPS is based on the following concepts:

• The NPS uses a modified version of the KIW2 framework of wilderness character

qualities, monitoring questions, and indicators to promote interagency consistency while

providing for park-specific flexibility (Table 2).

• Each selected indicator must have at least one corresponding measure. For the NPS,

not all indicators are required. The decision to omit an optional indicator(s) must be

paired with a thoughtful and documented rationale in the Wilderness Character Building

Blocks Report.

1. Optional indicator: ‘Actions not authorized by the federal land manager that

intentionally manipulate the biophysical environment’ (Untrammeled Quality)

2. Optional indicator: ‘Presence of inholdings’ (Undeveloped Quality)

3. Optional indicator: ‘Remoteness from sights and sounds of human activity

outside of wilderness’ (Solitude or Primitive and Unconfined Recreation Quality)

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 12

4. At least two measures for the Natural Quality must be selected (addressing a

minimum of two of the four indicators for this quality).

5. At least one measure for the Other Features of Value Quality must be selected

(addressing a minimum of one of the two indicators for this quality).

• Each NPS wilderness area has the flexibility to choose measures for the selected

indicators following the requirements above. No specific measures are required. For any

measure selected, thorough documentation of all measure components is critical.

• In general, measures selected for WCM should be:

o Useful: Select locally relevant measures that show how conditions are changing

over time and that are directly useful to stewardship decisions.

o Simple: Select the fewest measures that will credibly track change in the

indicator.

o Sustainable: Select measures that can be consistently monitored over time -

WCM is a long-term commitment.

3

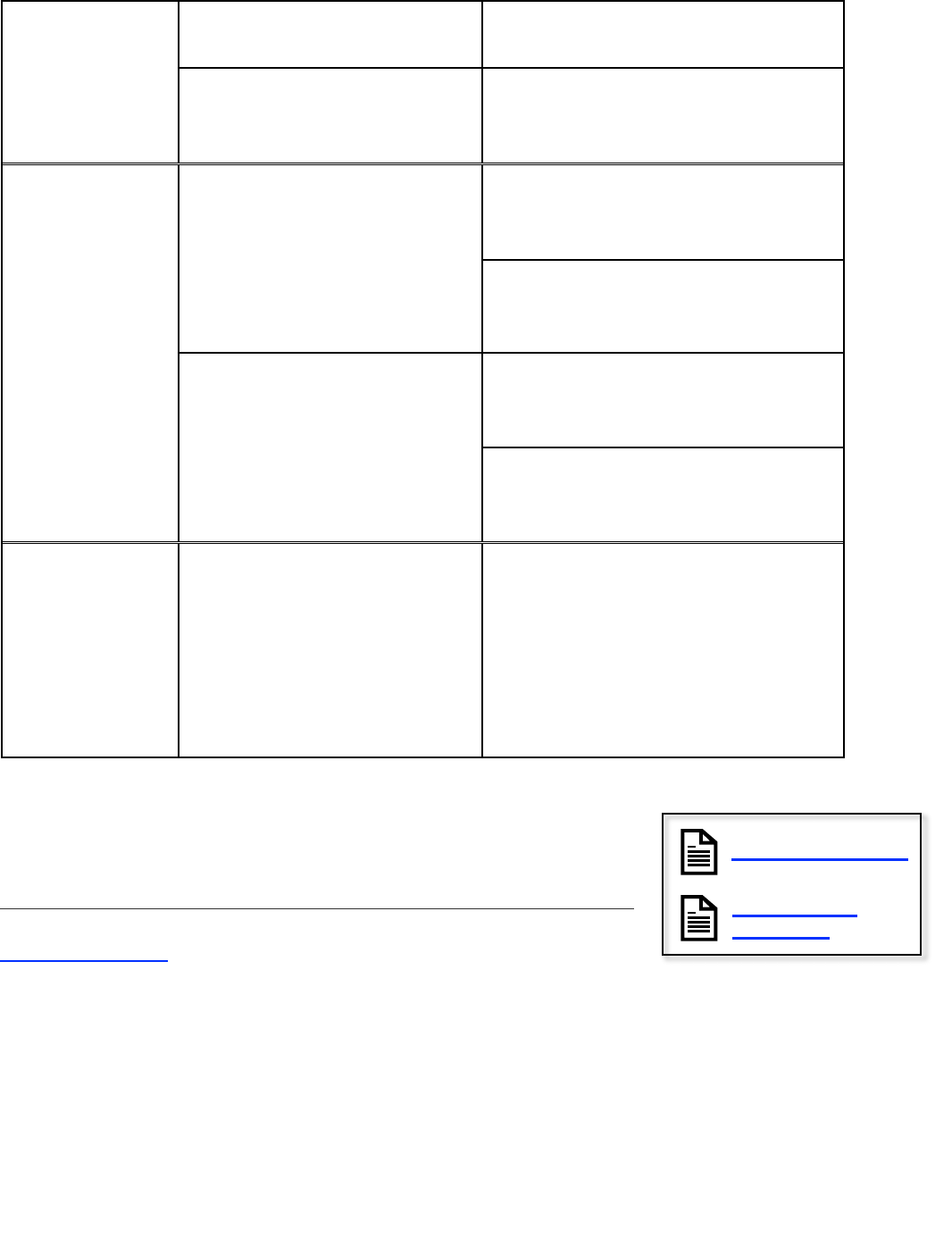

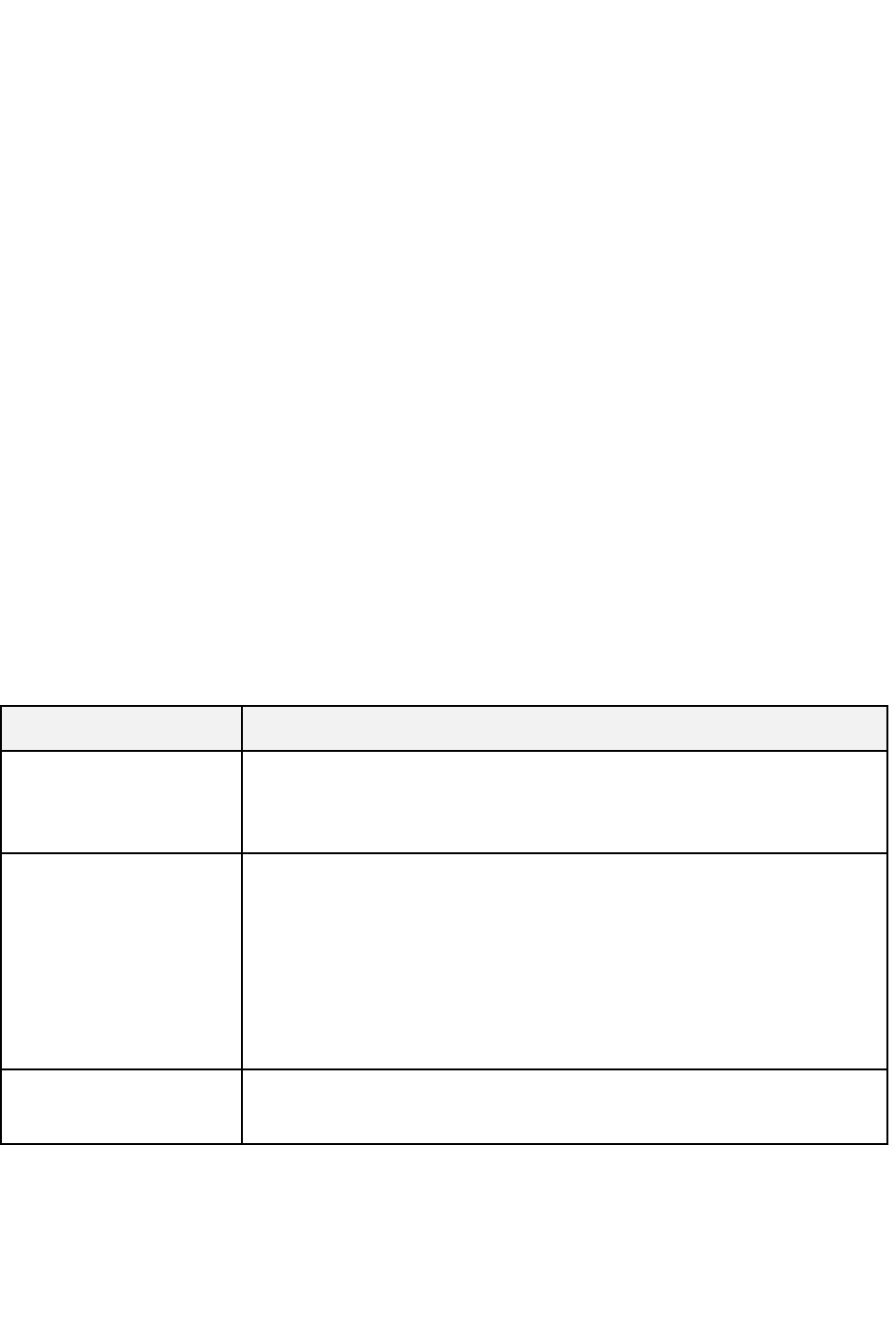

Table 2. Wilderness character qualities, monitoring questions, and indicators for the NPS

Quality Monitoring Question Indicator

Untrammeled

What are the trends in actions

that intentionally control or

manipulate “the earth and its

community of life” inside

wilderness?

Required:

Actions authorized by the federal land

manager that intentionally manipulate

the biophysical environment

Optional:

Actions not authorized by the federal

land manager that intentionally

manipulate the biophysical environment

Natural What are the trends in the

natural environment from

human-caused change?

Required - Select at least two of the

following:

Plants

Animals

Air and water

Ecological processes

Undeveloped What are the trends in non-

recreational physical

development?

Required:

Presence of non-recreational

structures, installations, and

developments

3

Sustainability is not a static concept. Future modifications to measures may be needed, but measures

should be selected after first considering the anticipated long-term implications of selecting the measure.

See the “Modifying the WCM Framework” section for more information.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 13

Optional:

Presence of inholdings

What are the trends in

mechanization?

Required:

Use of motor vehicles, motorized

equipment, or mechanical transport

Solitude or

Primitive and

Unconfined

Recreation

What are the trends in

outstanding opportunities for

solitude?

Required:

Remoteness from sights and sounds of

human activity inside wilderness

Optional:

Remoteness from sights and sounds of

human activity outside wilderness

What are the trends in

outstanding opportunities for

primitive and unconfined

recreation?

Required:

Facilities that decrease self-reliant

recreation

Required:

Management restrictions on visitor

behavior

Other Features

of Value

What are the trends in the

unique features that are tangible

and integral to wilderness

character?

Required - Select at least one of the

following:

Deterioration or Loss of Integral

Cultural Features

Deterioration or Loss of Other

Integral Site-Specific Features of

Value

NPS Example Measures and Measure Idea Templates

This Guide lists and describes at least one example measure for every

required and optional indicator in the NPS WCM framework. Additionally,

measure idea templates are offered for measures used by some parks.

Use of example measures and/or measure idea templates is not required.

Example measures give users of this Guide a sense of how a specific

park interpreted and implemented the intent of a specific indicator.

Considering example measures can prompt discussions that yield more meaningful measure

creation as parks proceed through the WCM process. Example measures are not required and

not intended for wide-spread use. If a park is inspired by an example measure, substantial place-

based modifications may be necessary, as measure components like thresholds for meaningful

change and frequency must reflect local context.

Measure Idea

Templates

Example Measures

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 14

Measure idea templates provide a modifiable structure for parks interested in using one or more

commonly used measures. The templates were co-created by NPS subject matter experts and

will be updated as needed.

The example measures and measure idea templates do not preclude a park from using other

measures (from existing monitoring efforts or newly created for WCM-specific purposes) to

locally address wilderness character. Remember, the primary purpose of WCM is to serve park-

identified wilderness stewardship needs. This purpose means all measures need to be locally

relevant and aid parks in understanding the state of wilderness character via specific

components of this large and complex concept.

THE WILDERNESS CHARACTER MONITORING PROCESS

Completing a wilderness character baseline assessment

There are five steps that should be taken by all parks to complete a wilderness character

baseline assessment.

Step 1: Ensure the wilderness boundary is accurate and available in GIS

Each wilderness area must have current and accurate geospatial boundary data to successfully

implement WCM. This GIS boundary information is a foundation for conducting more accurate

analysis and monitoring. Review the NPS Wilderness GIS Boundary Creation/Verification

Guidance to learn more.

Step 2: Holistically consider the WCM framework through the lens of park-identified

wilderness stewardship priorities

The wilderness character baseline assessment and monitoring are only as useful as the

intentionality that goes into identifying WCM details. Before diving into measure selection details,

parks are encouraged to take a step back and holistically consider the WCM framework through

the lens of park-identified wilderness stewardship priorities. Holistic consideration includes

involving perspectives from different park disciplines and initiating discussions with ample time to

discuss, reflect, and refine.

With the WCM framework of qualities, monitoring questions, and indicators in hand,

discussions can begin. Questions to guide these discussions include:

Wilderness Character Baseline Assessment in Five Steps

1. Ensure the wilderness boundary is accurate and available in GIS.

2. Holistically consider the WCM framework through the lens of park-identified wilderness

stewardship priorities.

3. Select measures, including identification of all measure components.

4. Confirm availability of measure data.

5. Compile and document the wilderness character baseline assessment

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 15

• Are there existing measures with available data that could provide important information

for the support of park wilderness stewardship, and thus should be considered in WCM

measure selection (e.g., desired conditions and thresholds associated with a Wilderness

Stewardship Plan)?

• What is considered the biggest threat(s) to wilderness character in terms of the X

indicator for the park?

• What are potential negative aspects of missing or ignoring changes in this threat(s)?

• Is there an aspect(s) of wilderness character that is especially well preserved/protected

right now? Why is this occurring? Is this something that needs to be monitored into the

future to ensure its continued preservation/protection?

• Is it worth using two or more different measures to holistically capture aspects of the X

indicator?

• Are there other aspects related to the X indicator that should also be considered?

• What data are or will be available to support each potential measure? Data includes

quantitative and qualitative sources.

• How should existing data and established protocol (versus creating something new that

is tailored to WCM) influence measure selection?

• What process will be used to develop and justify thresholds for meaningful change in

tandem with measure selection?

• How sensitive should the threshold for meaningful change be? Should it serve as a red

flag for coming change, or should it convey change that has clearly happened already?

• How might resulting trend conclusions (based on the measure and threshold for

meaningful change) potentially inform management or policy decisions?

Whether using these questions or others to think through the process of identifying WCM-

wilderness stewardship priorities, it is important that threats to wilderness character, as well as

current wilderness character preservation successes (that the park wants to continue or expand

on in the future), are identified prior to measure selection. This ensures time invested in WCM is

well-spent and yields helpful information for subsequent park planning, management, and

operations.

During this step, parks should also be aware of the individual measure components that inform

each measure. Notably, measures and thresholds for meaningful change should be

simultaneously identified. A threshold for meaningful change identifies what amount of change

in a measure qualifies as meaningful relative to wilderness character. Retroactively assigning a

threshold to an already selected measure may fail to identify change that meaningfully affects

wilderness character. Exploring measure options in tandem with thresholds for meaningful

change offers insight specific to park-identified wilderness stewardship priorities. For parks with

Wilderness Stewardship Plans, this includes considering how potential WCM thresholds for

meaningful change relate to plan components like thresholds and desired conditions. See the

“How WCM Relates to Wilderness Stewardship Planning, Compliance, and Operations” section

for more details.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 16

Step 3: Select measures, including identification of all applicable measure components

Once the WCM framework and park-specific wilderness stewardship priorities are holistically

considered, parks can select measures and identify details for all applicable measure

components. See the "Components Described for Each Measure” section for more information.

Remember, at least one measure must be identified for every required indicator, per the NPS

national WCM requirements.

Step 4: Confirm availability of measure data

If adequate data is available for all selected measures, proceed to Step 5.

In some cases, park-identified wilderness stewardship priorities may not

have relevant data immediately available for use in WCM. This is not a

dead end for engaging in the WCM process! Parks with WCM data gaps

should use the NPS Status Report for In-Progress WCM Baseline

Assessment Template to document their progress and help keep the

WCM process moving forward.

Step 5: Compile and document the wilderness character baseline assessment

The wilderness character baseline assessment is complete when there

is a baseline measure value for each selected measure (and there is at

least one measure for each required indicator). Once the wilderness

character baseline assessment is complete, a Wilderness Character

Building Blocks Report should be developed. This report documents a

park’s WCM framework, measures selected, measure components, and baseline measure

years and values. Some parks find it helpful to begin drafting the report in tandem with Step 2,

where all WCM framework details are documented in-real time rather than writing the report

afterwards. Parks are encouraged to use the Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report

Template

4

for the final report

5

.

When a draft Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report is complete, parks will submit the

draft to the NPS WASO Wilderness Stewardship Division for review

(wilderness_stewardship@nps.gov). Additional report reviewers are optional, including the NPS

Regional Wilderness Coordinator.

After the above reviews are complete, the park superintendent (or their designee) should

approve and sign the final Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report. This signature

validates the park’s wilderness character baseline assessment and indicates commitment to

4

The wilderness character building blocks include 1) the Wilderness Basics, 2) Wilderness Character

Baseline Assessment, and 3) Integrating Wilderness Character into Park Operations (not typically

documented in the Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report). Parks are encouraged to develop the

Wilderness Basics prior to initiating a baseline assessment. Learn more via the Wilderness Character

Building Blocks Resource Brief.

5

Optional publication of the Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report through the NPS Natural

Resource Report Series (NRR) is available.

NPS Status Report for

In-Progress WCM

Baseline Assessment

Template

Wilderness Character

Building Blocks

Report Template

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 17

ongoing WCM. Once signed, parks should provide a digital copy (or link) of the final report to

the NPS WASO Wilderness Stewardship Division.

In addition to the Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report, parks will need to enter their

wilderness character baseline assessment data into the WCM national database.

Process for using the WCM national database:

1. Complete the wilderness character baseline assessment and corresponding Wilderness

Character Building Blocks Report.

2. Identify the park’s data steward for data entry.

3. Email the NPS WASO Wilderness Stewardship Division

(wilderness_stewardship@nps.gov) to set-up a database account.

4. Enter wilderness character baseline assessment data in database.

5. Enter measure values for each five-year monitoring interval into the database. Data that

informs five-year reporting data (i.e., annual measure values) for each measure should

be logged and maintained on a park-managed database (or other record) at the intervals

defined in the protocol, as data can only be entered at five-year intervals in the national

database.

Components Described for Each Measure

Every measure used in WCM must describe the following components.

It is important to ensure appropriate documentation is provided for

each section.

Measure title. This is the title of the measure. Titles should be succinct

while providing enough detail to convey the purpose of the measure.

Context and relevance. This section explains why the measure is

relevant and gives background information that helps inform the reader

of context that ultimately led to the measure’s selection.

Definitions. This section defines terms relevant to understanding and

monitoring the measure. When used in a WCM context, some terms

have specific meanings which may not correspond to how managers otherwise use these terms

(such as “trammeling,” “installation”, and “development”).

Protocol. This section provides step-by-step instructions on how to implement and analyze the

measure, outlining the steps needed to arrive at a final reported measure value.

6

Protocol

should provide clear, repeatable instructions for monitoring. Modifications to protocol (that may

6

Protocol should reflect park-specific distinctions that make the measure both useful and feasible. For

example, parks may use a representative sample instead of a comprehensive inventory for count-based

measures. Other measures may outline a multistage approach, where one measure is used until

presence as a threshold is passed (e.g., presence of XX detected where previously XX did not exist),

followed by a shift to a measure accounting for potential and observed impacts after presence has been

confirmed.

Measure Components

Measure title

Context and relevance

Definitions

Protocol

Data sources

Data adequacy

Frequency

Threshold for meaningful change

Caveats and cautions

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 18

emerge over time) should also be documented here, noting the full sequence of original to

modified protocol, so as to give the reader context for potentially observed discrepancies. See

the ‘Modifying the WCM Framework’ section of this Guide for more details.

Data sources. This section identifies the source(s) and location(s) of the data used for WCM.

Data can include qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methodology sources. To be clear, well

documented professional judgment and other qualitatively described subject matter expertise is

an appropriate data source for WCM. For all data sources, details for locating data should be

documented, including links to online data sources, pathways for digital documents located on

network drives, and descriptions of where to find hard-copy files.

Data adequacy. This section addresses the reliability of the data to assess trends in the

measure. It encompasses both data quality and data quantity. Data adequacy is an assessment

of the reliability and confidence in the data used for each measure -- determined by assessing

data quantity and quality. Each measure describes both data quantity and quality, using the

assessment metrics below, and concludes with an overall data adequacy “rating.”

Data quantity refers to the level of confidence that all necessary and appropriate data records

have been gathered. In determining the best available information for a park, “available” refers

to information that currently exists in a useful form, and that does not require further collection,

modification, or validation. If the available data are insufficient in quantity, they may still be

considered the best available information for the park. Data quantity is described by the

following three categories, determined by the park:

1. Complete—This category indicates a high degree of confidence that all necessary and

appropriate data records have been gathered.

2. Partial—This category indicates a medium degree of confidence that all necessary and

appropriate data records have been gathered. Some data are available but are generally

considered incomplete.

3. Insufficient—This category indicates a low degree of confidence that all necessary and

appropriate records have been gathered. Few or no data records are available.

Data quality refers to the level of confidence about the data source and whether the data are of

sufficient quality to reliably identify trends in the measure. Data quality is assessed by the data’s

accuracy (the degree to which the data express the true condition of the measure and not other

sources of variation affecting the measure), reliability (the degree to which the data follow

established or well-developed protocols), and relevance (the degree to which the data are

spatially and temporally appropriate for the measure). In general, the highest quality data will be

considered the best available information. Remember, WCM data can be quantitative,

qualitative, or mixed methodology. Data quality is described by the following three categories,

determined by the park:

1. Good—This category indicates a high degree of confidence that the quality of the data

can reliably assess trends in the measure. Data are highly accurate, reliable, and

relevant for the measure.

2. Moderate—This category indicates a medium degree of confidence about the quality of

the data. Data are only moderately accurate, reliable, or relevant.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 19

3. Poor—This category indicates a low degree of confidence about the quality of the data.

The accuracy, reliability, or relevancy of the data is minimal or unknown.

Parks must evaluate data quantity and quality for all potential data sources. An overall

determination of data adequacy is derived by combining the assessments of quality and quantity

(Table 3) and is categorized as high, medium, or low. Numerical values are included as an

optional level of detail to document the data adequacy ‘rating’.

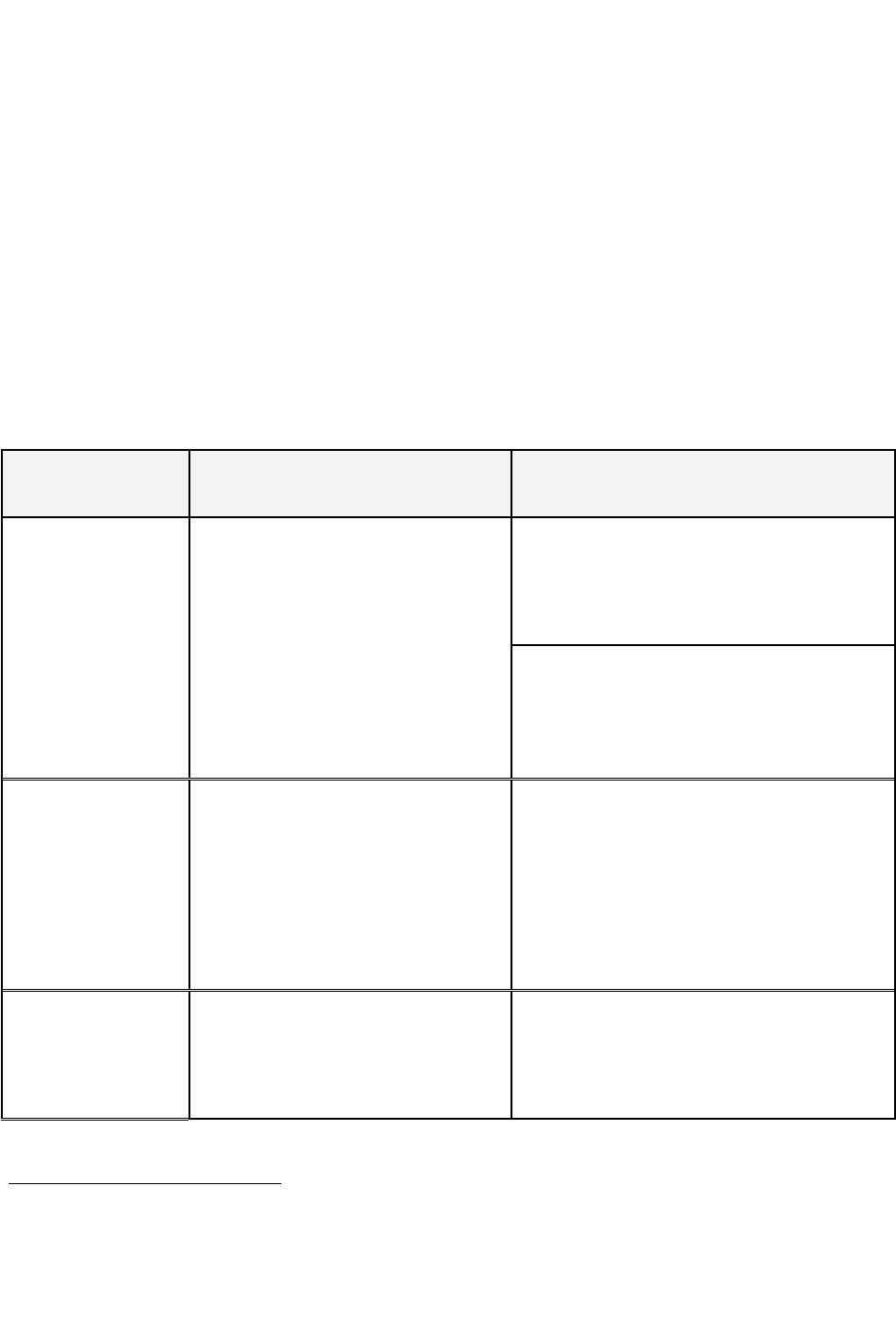

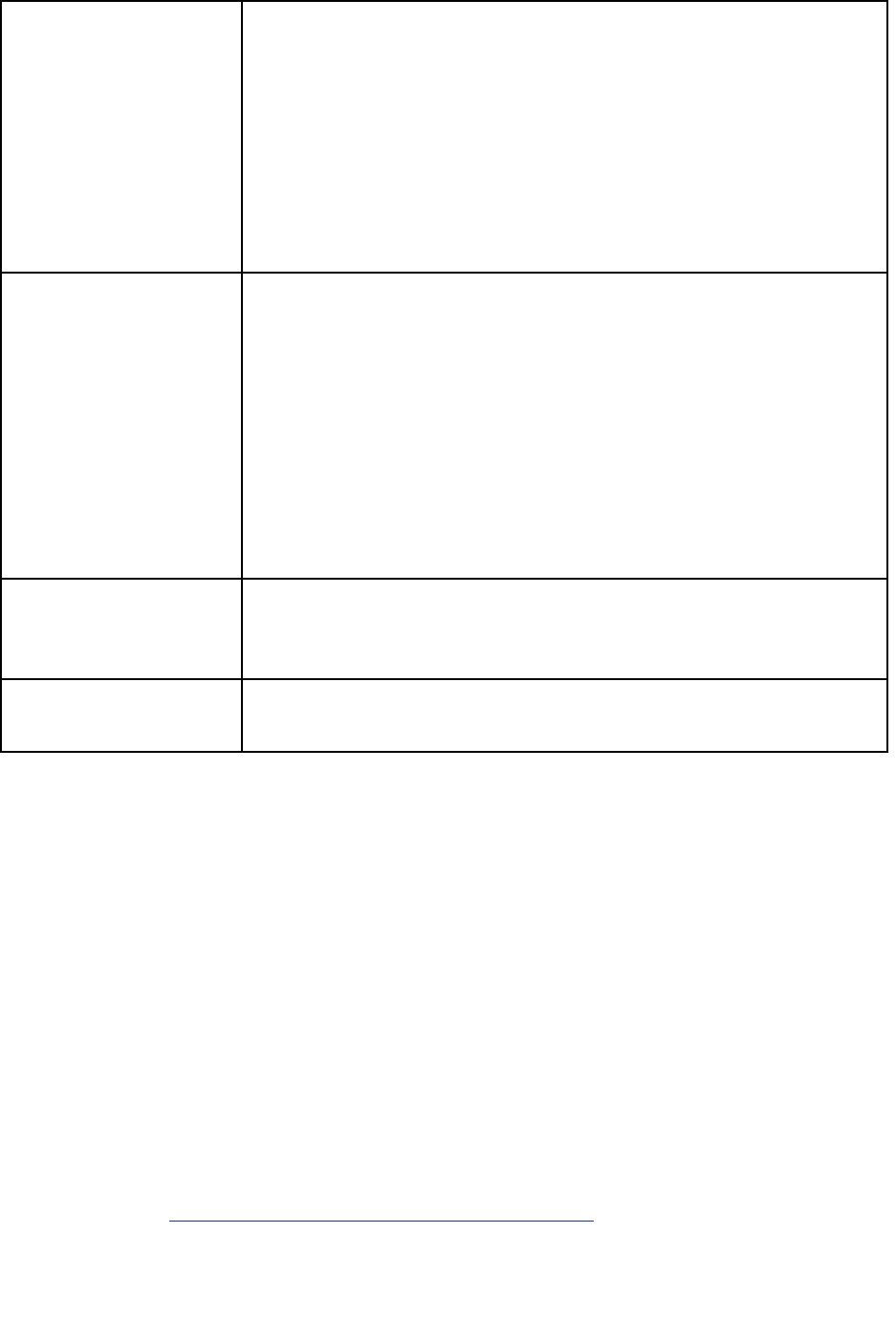

Table 3. Data Adequacy Rating Table

Data Quantity + Data Quality = Data Adequacy

Complete (3)

+

Good (3)

=

High (6)

Partial (2) Moderate (2) Medium (4-5)

Insufficient (1) Poor (1) Low (<3)

There is no minimum data adequacy rating required to use a particular data source. Instead,

determining data adequacy ensures the park is aware of the tradeoffs of using the identified

data source (tradeoffs that should be well documented in the Wilderness Character Building

Blocks Report). Similarly, the data adequacy of a seemingly similar data source may vary from

park to park. For example, data relying on professional judgment may receive a medium or high

data adequacy rating at park A due to the degree of detail documented over a long timeframe,

whereas park B considers data from professional judgment to be a low data adequacy rating

because little is documented, and the primary source is unavailable to interview further.

While data adequacy is not used to determine a measure’s trend, it is crucial for interpreting

trends (e.g., if there is a declining trend but data adequacy is low, then confidence in this trend

would also be low) and for revealing when additional or different data collection efforts may be

needed.

Frequency. This section identifies how often measures should be monitored to determine a

reported measure value. In some cases, measures will only be monitored once every five years,

in accordance with the WCM minimum monitoring frequency requirement. In other instances,

the reported measure value for the five-year monitoring interval is a composite of multiple

measure values collected in between the current and previous monitoring interval.

Threshold for meaningful change. This section explores how change in a measure affects

wilderness character. This section helps distinguish WCM from other NPS monitoring efforts

because it links the measure’s intent and corresponding measure value to wilderness character

impacts.

As Step 2 of the “Completing a Wilderness Character Baseline Assessment” section

indicates, thresholds for meaningful change should be determined in tandem with selecting

the measure to ensure a park is measuring something that can affect wilderness character.

Arriving at this determination requires discussion, considering questions like:

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 20

• What process will be used to develop and justify thresholds for meaningful change in

tandem with measure selection?

• How sensitive should the threshold for meaningful change be? Should it serve as a red

flag for coming change or should it convey change that has clearly happened already?

• How do potential thresholds for meaningful change relate to thresholds and desired

conditions identified in park planning documents, like a Wilderness Stewardship Plan?

• How do potential thresholds for meaningful change relate to the condition of wilderness

character?

The process of determining thresholds for meaningful change is subjective because it typically

depends on place-based professional judgment. There is no ‘objective’ process that can make

this decision for managers. The complexity, nuance, and context present in a wilderness area

must all be accounted for when determining thresholds for meaningful change. This subjectivity

means that thresholds for meaningful change will likely differ from park to park. Examples of

thresholds for meaningful change include, but are not limited to any change, additive change,

percent or multiplicative change, and in some instances, statistical reasoning (if assumptions

are assessed).

Caveats and cautions (if applicable). This section describes considerations or other relevant

context to keep in mind for the measure. Documentation may expand on known concerns with

the measure or make note of potential future modifications that should be revisited during the

next monitoring interval.

Key Principles of WCM

To successfully implement this monitoring, NPS staff need to understand the following

principles:

A park’s WCM framework is likely to change over time — Consistently using the same

measures and measure components over time to determine trends in wilderness character is

ideal - but parks should be prepared to evolve and make thoughtful changes if needed.

Changes may be prompted by new issues or policy direction, the emergence of new data

sources that better address local wilderness stewardship priorities, etc. See the “Modifying the

WCM Framework” section for more details.

Lands designated or managed as wilderness are living cultural landscapes. Thoughtful

consideration should be given to cultural practices and traditions while identifying wilderness

stewardship priorities that are related to WCM — Wilderness character is a combination of

many interrelated factors. These factors inform a park’s identified wilderness stewardship

priorities and the threats and successes for wilderness character preservation. Because

wilderness lands are a living cultural landscape, managers should be sensitive to how

wilderness stewardship priorities are determined and framed, demonstrating sensitivity for past

and ongoing cultural practices and traditions that may intersect with factors influencing

wilderness character.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 21

Management actions often impact more than one quality of wilderness character. For practical

reasons, not all qualities impacted may be monitored — Generally speaking, actions that affect

more than one quality of wilderness character will be measured only for the quality that is most

directly impacted. This helps prevent redundancy in the influence of that action on trend

determinations. However, if a park feels strongly that an action should be evaluated through the

lens of multiple qualities, and appropriate measures are selected, this is also acceptable. In this

instance, an explanation for its inclusion (and recognition of potential redundancy) needs to be

documented in the ‘Caveats and cautions’ component of the measure.

Management decisions may preserve or degrade these qualities, and cumulative impacts matter

– Wilderness character may be improved, preserved, or degraded by the actions managers

decide to take or not take. Protecting one quality of wilderness character may diminish another.

Over time, tradeoffs affecting different qualities of wilderness character and the cumulative

results of seemingly small decisions and actions may cause a significant gain or loss of

wilderness character. With an established WCM framework to discuss these tradeoffs within the

context of wilderness character and its five tangible qualities, managers have a tool (to use

alongside other tools) that helps to preserve wilderness character as a whole.

Measures that are integral to wilderness character may be monitored, regardless of managerial

jurisdiction — Resources that are integral to the area’s wilderness character, but that are not

directly under the jurisdiction of managers, are included in this monitoring to the extent that is

practical.

Selective use of site-specific measures is permitted — While WCM focuses on monitoring

trends in wilderness character across an entire wilderness area, it is not always practical to

exclusively select measures that can be monitored area-wide. For instances where a site-

specific measure (i.e., portion(s) of the wilderness area that does not encompass the entirety of

the wilderness area) enables a park to meaningfully measure something of high priority, a site-

specific measure is appropriate. The rationale for using a site-specific measure, and

acknowledgement of the tradeoffs for this decision, should be documented in the Wilderness

Character Building Blocks Report.

Long-term Wilderness Character Monitoring

WCM does not end with the wilderness character baseline assessment. Long-term monitoring is

the recurring monitoring of measures according to protocol described in a park’s Wilderness

Character Building Blocks Report (and subsequent WCM framework modification protocol).

Monitoring intervals will depend on measure-specific protocol described in the report. At a

minimum, this monitoring will occur every five years to identify current reported measure values.

The reported measure values will be compared to the baseline measure values to determine

trend.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 22

For the five-year reporting intervals, parks are encouraged to use the

WCM Five-Year Reporting Summary Template to document measure

values and changes or trend. The summary can be appended to the

Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report for co-reference. Parks

will also need to enter the current reported measure values into the

WCM national database.

Determining Trend in Wilderness Character

Assessing overall trend in wilderness character provides a readily interpretable conclusion that

can help inform future management actions to better preserve wilderness character over time. A

trend of improving, stable, or declining is derived for each measure based on the comparison of

the reported measure to the baseline measure value and the corresponding threshold for

meaningful change

7

. This yields a trend determination at the measure level, which is then rolled-

up to determine trend at the indicator, monitoring question, and quality levels, culminating in a

trend for overall wilderness character of the wilderness area. Trend roll-ups are determined

using nationally consistent, interagency rules. These rules are described in KIW2’s “Assessing

Trend in Wilderness Character” section. The NPS distinction between official trend and change

differs from KIW2 guidance – while KIW2 rules for trend roll-ups still apply, parks should refer to

this Guide when deciding the point at which trend can be assessed in a measure

8

.

Modifying the WCM Framework

Change is inevitable and measure components, like data sources, protocol, thresholds for

meaningful change, and even overall measures are subject to change. When parks consider

making a modification to part of their WCM framework, focused discussions about tradeoffs to

proposed modifications should happen first, with interdisciplinary representation. Parks may

also contact their Regional Wilderness Coordinator and the WASO Wilderness Stewardship

Division to discuss the appropriateness and feasibility of proposed modifications.

Documenting modifications

When modifications are agreed-upon and finalized, documentation is a must. Parks should

update the Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report and/or WCM Five-Year Reporting

Summary with:

• The specific modification

• Date of the modification

• The reason(s) for this decision

• The potential impact(s) on interpreting trend in wilderness character

7

Trend is officially determined by comparing the current ‘reported measure value’ to the ‘baseline

measure value’ if the current ‘reported measure value’ includes a minimum of five data points. Trend is

determined by the measure’s corresponding ‘threshold for meaningful change’ to help interpret the

comparison and conclude if the trend is improving, stable, or declining. Absent the availability of five data

points, ‘change’ (rather than trend) between current and baseline measure values can still be discussed

and documented. Assessing changes in wilderness character prior to formal trend conclusions can yield

helpful information for managers that is further strengthened through trend assessments.

8

Within this Guide, references to ‘trend’ also represent ‘change’ where appropriate, based on the

limitations of how ‘change’ is defined.

WCM Five-Year

Reporting Summary

Template

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 23

Modification impacts on determining trend

Depending on the specifics of the modification, this may substantially impact a trend

determination. Since trend is a comparison of the current reported measure value to the

baseline measure value (according to the threshold for meaningful change), a substantial

modification may mean the current measure is fundamentally different from the baseline

measure, making a comparison difficult. In cases where substantial discrepancies occur, parks

have two options:

1) Acknowledge the discrepancy in the five-year monitoring interval

Document the discrepancy and skip the trend determination for that particular measure during

the five-year monitoring interval the change occurred. If there is only one measure for the

required indicator, this also means there will be no trend for the indicator.

• Example: Park X’s baseline assessment included one measure about natural landcover

for the ‘Ecological Processes’ indicator (no other measures were used for this indicator).

Five years later, when the park was assessing trend between the baseline and first

monitoring interval, staff determined the natural landcover measure did not sufficiently

address the park’s wilderness stewardship priorities. Instead, the park wanted to use a

fire-related measure that they would begin collecting data on that year (establishing a

baseline measure value). Meanwhile, all other measures had not only a baseline

measure value, but a second reported measure value generated during the first

monitoring interval. The park decided to retain the original overall WCM baseline year

and assess trend for all other measures during this monitoring interval. This allowed the

park to also roll-up trend at all other levels of the WCM framework, recognizing that the

Ecological Processes indicator did not influence trend roll-ups because there was no

trend to report on. The next monitoring interval will resume inclusion of all measures

used as there will be a new reported measure value for the fire measure. This will allow

for the second trend assessment to include the Ecological Processes indicator too.

• Parks should be clear that this choice means an overall trend determination for

wilderness character is less holistic than prior or future monitoring intervals because

some aspects of wilderness character represented by the measure and/or indicator are

absent. Documentation of the rationale for this tradeoff is essential.

2) Revise the wilderness character baseline assessment

Update the wilderness character baseline assessment with the identified modification(s).

Depending on the details of the modification(s), this may result in changes to the measure

baseline year and the WCM baseline year too.

• Example: Using the same example as above, Park X’s baseline assessment included

one measure about natural landcover for the ‘Ecological Processes’ indicator (no other

measures were used for this indicator). Five years later, when the park was assessing

trend between the baseline and first monitoring interval, staff determined the natural

landcover measure did not sufficiently address the park’s wilderness stewardship

priorities. Instead, the park wanted to use a fire-related measure that they would begin

collecting data on that year. The park felt strongly that this new measure should

influence how trend is assessed for the park and thus opted to reset the overall WCM

baseline year to accommodate inclusion of this new measure. The park will postpone

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 24

assessing trend until the second monitoring interval when every measure has a current

reported measure value to compare against the baseline measure value.

• Parks should be clear that this choice maintains best practices for determining trend,

supporting the holistic consideration of wilderness character. However, this approach

can set back the overall monitoring timeline, affecting the time before trend can be

determined. In other instances, these changes may not affect the trend timeline (e.g., a

new data set used has the same length of availability as the previously used data set; a

new approach to identifying thresholds for the measure does not affect when measure

values can be reported; etc.).

How This Guidance Relates to Parks That Have Already Implemented WCM

Parks that have already implemented WCM prior to the release of this Guide will need to

confirm that their monitoring protocol follows the NPS modified WCM framework described in

the “National WCM Framework” section. For WCM framework components that need updating,

the same two options apply as described in the “Modifying the WCM Framework” section. These

options apply not only to single measure changes, but other parts of the WCM framework

including the omission of now-optional indicators and now-required use of the Other Features of

Value Quality.

Roles and Responsibilities

Implementing WCM at a park is a collaborative effort between park staff, the region, the WASO

Wilderness Stewardship Division, and technical specialists. Table 4 describes the different

groups involved in WCM and their respective roles.

Table 4. NPS groups and their respective WCM roles

NPS Group WCM Role(s)

Park wilderness

coordinator

• Coordinate the development of the wilderness character

baseline assessment, documented in the Wilderness Character

Building Blocks Report.

Park interdisciplinary

staff

• Develop wilderness character baseline assessment, and

document in the Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report.

• Monitor wilderness character on a five-year interval minimum,

documented through the WCM Five-Year Reporting Summary.

• Enter wilderness character baseline assessment and

monitoring data into the WCM national database every five

years.

Park superintendent

• Review, approve, and sign Wilderness Character Building

Blocks Report.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 25

Regional Wilderness

Coordinators

• Support parks in developing wilderness character baseline

assessments and monitoring, including assistance with

identifying regional datasets, expertise, and potential

supplemental funding sources.

• Review and sign (for concurrence) Wilderness Character

Building Blocks Reports as needed (prior to Superintendent’s

signature).

• Liaise between the parks and WASO Wilderness Stewardship

Division for emergent WCM needs/issues.

WASO Wilderness

Stewardship Division

• Support park-based development of wilderness character

baseline assessments and monitoring, including assistance

with identifying national datasets, expertise, and potential

supplemental funding sources.

• Review and sign (for concurrence) Wilderness Character

Building Blocks Report (prior to Superintendent’s signature).

• Manage access to the WCM national database.

• Generate servicewide wilderness character trend reports as

appropriate.

• Update WCM policy and guidance as needed.

Other NPS Washington

Support Offices

(WASO)

• Support WCM through data collection, data access, or subject

matter expertise.

Interagency WCM Work

Group

• Coordinate WCM efforts between agencies.

Updating this Guide

The NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide will be updated and reviewed

periodically, coordinated by the NPS Wilderness Stewardship Division. These changes will be

catalogued, allowing users to access the most current version.

How WCM Relates to Wilderness Stewardship Planning, Compliance, and Operations

WCM should directly inform a Wilderness Stewardship Plan (WSP) (or equivalent plan), but it is

not a WSP itself. Ideally, parks would complete a WCM baseline assessment, documented in

the Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report, early in the WSP planning process (if this

assessment has not already been completed).

The WCM framework helps clarify park-specific wilderness stewardship priorities and results of

the WCM baseline assessment are the reference point for future wilderness character trend

determinations. These priorities and trend details can help inform desired conditions, standards,

management actions, and other planning components within WSPs (see Figure 1: WSP

Framework in the NPS Wilderness Stewardship Plan Handbook).

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Foundational Information | Page 26

WCM is not a singular decision or management plan. WCM should help inform planning efforts

involving wilderness - any decisions informed by WCM results are subject to other federal laws

(Americans with Disabilities Act, Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act,

National Environmental Policy Act, National Historic Preservation Act, etc.) and NPS policy

requirements.

WCM should also be used as a means of informing priorities and needs for ongoing wilderness

stewardship operations.

The procedures outlined in this Guide meet the following compliance criteria established in the

NPS NEPA Handbook, Section 3.2 – Categorical exclusions for which no documentation is

required: “Plans, including priorities, justifications, and strategies, for non-manipulative research,

monitoring, inventorying, and information gathering.” The authority for categorically excluding an

action rests with the park unit’s superintendent (Director’s Order 12, Section 5.4).

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Untrammeled Quality | Page 27

Untrammeled Quality

The objective of monitoring the Untrammeled Quality is to assess

whether management of a wilderness area is trending over time toward

more or less intentional human manipulation of the biophysical

environment and community of life. Section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act

defines wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of

life are untrammeled by man,” that “generally appears to have been affected primarily by the

forces of nature” and is an area “retaining its primeval character and influence.”

The Untrammeled and Natural Qualities are closely related, though they differ in a key way—the

Untrammeled Quality examines actions that intentionally control or manipulate ecological

systems inside wilderness, whereas the Natural Quality examines the effects on these systems

from actions taken inside wilderness or from external forces, regardless of management

objective. Separating actions from effects offers a clearer distinction between these two qualities

and their influence on overall wilderness character.

The Untrammeled Quality is explored through one monitoring question, one required indicator,

and one optional indicator.

MONITORING QUESTION: What are the trends in actions that intentionally control or

manipulate “the earth and its community of life” inside wilderness?

This single monitoring question for the Untrammeled Quality examines actions that intentionally

control or manipulate the components or processes of ecological systems inside wilderness. In

this context, intentional manipulation means an action that deliberately alters, hinders, restricts,

controls, or manipulates “the earth and its community of life.” This includes actions that affect

plants or animal species, insects and disease pathogens, physical resources (e.g., water or

soil), or biophysical processes (e.g., fire) inside a wilderness area.

When monitoring the Untrammeled Quality, all trammeling actions are counted the same

regardless of the area, intensity, frequency, or duration of their effects. This is because the

Untrammeled Quality focuses on whether a particular decision to manipulate “the earth and its

community of life” is made, not on the magnitude of that decision. In other words, taking any

trammeling action degrades the Untrammeled Quality, regardless of its scope and scale. For

practical reasons, however, this Guide considers magnitude when questions arise as to whether

a seemingly inconsequential action truly manipulates “the earth and its community of life” and

should be addressed.

Actions that degrade the Untrammeled Quality are typically the result of administrative decisions

made by managers. However, intentional activities by other federal and state agencies, non-

governmental organizations, or the public may also affect this quality. For this reason, parks are

required to monitor authorized trammeling actions and can optionally monitor unauthorized

trammeling actions if these actions are of high interest to the park and sufficient data sources

exist to monitor.

Essentially unhindered and

free from the intentional

actions of modern human

control or manipulation.

National Park Service Reference Manual 41: NPS Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide (version 1.0)

Untrammeled Quality | Page 28

REQUIRED INDICATOR: Actions authorized by the federal land manager that

intentionally manipulate the biophysical environment

This indicator tracks all significant actions authorized by the park that intentionally manipulate

the biophysical environment, including those allowed under Section 4(d)(1) of the Wilderness

Act (which states “measures may be taken as may be necessary in the control of fire, insects

and disease, subject to such conditions as the Secretary deems desirable”). Intentional

manipulations taken by other federal agencies, state and tribal agencies, and private citizens

are included under this indicator if these actions are authorized by the park that manages the

wilderness. Trend in this indicator tracks whether managers are practicing restraint to allow a

wilderness area to exist in its free and self-willed condition.

OPTIONAL INDICATOR: Actions not authorized by the federal land manager that

intentionally manipulate the biophysical environment

This optional indicator attempts to identify actions that have not been authorized by the park that

intentionally manipulate the biophysical environment. Given the challenge to confidently account

for unauthorized actions, this indicator is not required and can be skipped if accompanied by a

thoughtful documented justification in the Wilderness Character Building Blocks Report.

For parks where unauthorized trammeling actions are of high concern and data adequacy is

reasonable, use of this indicator is encouraged. Unauthorized intentional manipulations of

plants, animals, physical resources, or biophysical processes within wilderness have the

potential to affect all qualities of wilderness character. These actions are fundamentally different