Scholarship Repository

University of Minnesota Law School

Articles Faculty Scholarship

2023

Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence: A Comparative Law Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence: A Comparative Law

and Economics Analysis and Economics Analysis

Francesco Parisi

University of Minnesota Law School

Giampaolo Frezza

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles

Part of the Law Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Francesco Parisi & Giampaolo Frezza, Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence: A Comparative Law

and Economics Analysis, 9 Italian Law Journal 77-100 (2023)

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been

accepted for inclusion in the Faculty Scholarship collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship

Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected].

Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence:

A Comparative Law and Economic Analysis

Francesco Parisi

*

and Giampaolo Frezza

**

Abstract

Inherent in any judicial system is the need to allocate the burden of proof on one party.

Within the realm of negligence torts, that burden is traditionally placed on the plaintiff,

meaning that the plaintiff must bring forth sufficient evidence to establish negligence by the

defendant. In effect, this is a legal presumption of non-negligence in favor of the defendant. In

some jurisdictions for specific torts, defendants are, instead, presumed negligent, therefore

requiring defendants to come forth with sufficient evidence to prove their due diligence. In

this paper, we discuss the legal origins and effects of these differences in a comparative law

and economics perspective. We explore the interesting interaction between evidence and

substantive tort rules in the creation of care and activity level incentives and discuss the

ideal scope of application of alternative legal presumptions under modern-age evidentiary

technology.

I. Introduction

Recent scientific and technological innovations have changed the landscape

of evidence practice quite substantially. New frontiers of evidence have been made

possible by genetic testing, computer recording of data, digital timestamping,

third-party certified data storage systems, black-box technology, traffic surveillance

cameras, satellite imaging, Snapshot

®

technology, and GPS tracking devices.

Though the usefulness and invasiveness into our private lives remain relevant

normative questions, these transformations have changed our routine information

protocols. Scientific and technological advances will continue to provide new

opportunities and open new horizons in the domain of legal evidentiary discovery.

Legal presumptions play two interrelated roles in negligence cases. First,

legal presumptions allocate the burden of proving negligence between the parties.

1

Oppenheimer & Donnelly Professor of Law, University of Minnesota, School of Law and

Professor of Economics, University of Bologna.

Provost and Professor of Private Law, University of Rome, LUMSA, Faculty of Law.

The authors would like to thank Michael Bennett, Ryan Fitzgerald, Nuno Garoupa, Alice

Guerra, Marco Li Pomi, Symeon Symeonides, and the participants to the 2021 Annual Conference of

the American Society of Comparative Law for valuable comments and suggestions.

1

The way in which allocation of the burden of proof affects both care decisions and incentives

to invest in information is well known outside the area of negligence liability, such as pointed out

in the context of US toxic torts by W.E. Wagner, ‘Choosing Ignorance in the Manufacture of

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 78

Given the differing accessibilities to relevant evidence and information by the

parties, this may affect a court’s ability to assess the defendant’s negligence in the

case at hand. Second, the use of different legal presumptions can affect the parties’

expected liability and their incentives with respect to both care and activity levels.

In this paper, we employ a comparative law and economics perspective to

attempt to understand the interdependent relationship between new evidentiary

technology, legal presumptions, and discovery rules, with special focus on

negligence liability. The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we survey the

different legal presumptions of negligence used in European legal systems from

a historical and comparative perspective, with special attention to the rules

governing traffic accidents. Our analysis builds upon two separate bodies of

literature looking at the interaction between evidentiary and substantive rules in

tort law. We consider some of the theoretical and practical difficulties in the adoption

of presumptions of negligence. We examine the ‘cheapest evidence-producer’

criterion elaborated in the current literature and discuss the applications of this

criterion in the context of the US and European rules. In Section 3, we consider

the interrelated effects of legal presumptions on the parties’ tort incentives and

incentives to invest in private evidence technology. We discuss the possible

diluting effects of alternative discovery regimes on the parties’ incentives to adopt

evidence technology. Section 4 concludes with policy considerations.

II. Presumptions of Negligence

The need to allocate the burden of proof on one party is inherent in any

judicial system. Traditionally, within the realm of negligence torts, that burden is

placed on the plaintiff. This means that the plaintiff must bring forth sufficient

evidence to establish negligence by the defendant. In effect, this is a legal

presumption in favor of defendants.

2

In some European jurisdictions, defendants

Toxic Products’ 82 Cornell Law Review, 773, 774–75 (1997). See also, eg, Restatement (Third)

of Torts: Products Liability §2 comment a (‘To hold a manufacturer liable for a risk that was not

foreseeable when the product was marketed might foster increased manufacturer investment in

safety. But such investment by definition would be a matter of guesswork’).

2

To frame the scope of our analysis, we should clarify some of the terminology that will be

used in our analysis, distinguishing interrelated concepts that are commonly associated with the

notion of ‘burden of proof.’ These concepts are operationally interdependent, but theoretically

distinct: ‘legal presumptions’, ‘burden of production,’ and ‘burden of persuasion.’ Legal presumptions

are rules that allocate the initial burden of production of evidence, specifying which party is

required to ‘produce’ the evidence (or, as J. Adler and M. J. Michael, The Nature of Judicial

Proof: An Inquiry into the Logical, Legal, and Empirical Aspects of the Law of Evidence (1931), 63

put it, which party has the ‘burden of coming forward with the evidence’). A favorable presumption

shifts the burden (and costs) of producing evidence on the other party. The concept of burden of

persuasion, instead, defines how evidence should be weighted and ‘how much’ probative evidence

should be offered to convince the fact finders. Standards of proofs, such as ‘reasonable possibility,’

‘preponderance of the evidence,’ ‘clear and convincing evidence,’ or ‘beyond a reasonable doubt,’

are standards that determine the applicable burden of persuasion. In this paper, we focus on the

79 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

are presumed negligent for specific torts, therefore requiring the defendant to

produce sufficient evidence of their non-negligence. These rules have gone through

periods of reformulation as the underlying principles of evidentiary production

and presumptions of negligence have changed.

1. Legal Socialism and the Origins of Presumed Negligence

Across European legal systems there are many diversified models of

presumptions of negligence.

3

In several countries, the fault principle of ‘no

liability without negligence’ is strongly rooted, so most presumptions of negligence

have been introduced by special legislation. Because presumptions of negligence can

easily lead to presumed liability, or ‘semi-strict liability’, many countries have

found difficulty in accepting alternative presumption of negligence regimes. This

creates a tension with the underlying traditional general fault principle: in the

absence of proof of negligence, judges must leave things as they are.

4

Outside the area of traffic accidents, we can find trace the earlier examples

of rules of presumed negligence in modern codifications to the provisions

contained in the code Napoléon of 1804.

5

In particular, Arts 1384, 1385, 1386 (in

the original version of the code) established liability for (i) custodians of property

that cause harm; (ii) parents for the harm caused by their cohabiting minor

children; (iii) employers for the harm caused by their employees; (iv) teachers

and craftsmen for the harm caused by their students and apprentices; (v) owners

of animals, or whoever is using the animal, for the harm the animals caused; and

(vi) owners of buildings for the harm caused by their collapse or destruction. In

their original formulation, however, these presumptions were a form of presumed

liability that did not admit rebuttal evidence and did not allow for avoidance of

liability (eg, fortuitous event or force majeure). These exceptions were only introduced

by French courts later in the 19

th

century, following the spread of civil wrongs

brought about by the industrial revolution.

6

Rules of presumed negligence have

effect that changes in the burden of producing evidence have on the parties’ care and activity level

incentives. Hereinafter, we’ll refer to the burden of production as ‘burden of proof.’ We compare the

traditional rules that place the initial burden of proof on the plaintiff (we refer to these rules as

‘presumptions of non-negligence’), to the alternative rules introduced in Europe that have reallocated

the burden of proof on the defendant (we refer to these rules as ‘presumptions of negligence’). These

legal reforms have not modified the standards of proof applicable to the case, so we will set that

dimension of the probatory problem aside for the purpose of our analysis.

3

See G. Alpa, La responsabilità civile, Trattato di diritto civile (Milano: Giuffrè, 1999), 313.

4

In these jurisdictions, only the legislature can introduce new cases governed by strict

liability. This is because strict liability is still considered one of the exceptions to the general fault

principle governing tort liability. Extensive interpretations or applications by analogy of the legal

presumptions of negligence would thus be inadmissible, since they would de facto introduce

new areas of semi-strict liability, infringing the general principle of fault liability.

5

See generally, M. Comporti, Fatti illeciti: le responsabilità presunte, Il Codice Civile

Commentario (Milano: Giuffrè, 2012), 99.

6

See F. Laurent, Principes de droit civil (Paris: Librairie A. Marescq, Aine, 1878), 691; L.

Josserand, Cours de droit civil positif français (Paris: Recueil Sirey, 1932), 523–53; R. Demogue,

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 80

later appeared in several other European codifications.

Like the code Napoléon, the Spanish legal system included rules of presumed

liability in special circumstances which depart from the otherwise applicable

fault principle. Art 1903 of the Spanish Civil Code of 1889 encompasses these

forms of civil liability in a single provision, specifying that the obligations are

enforceable ‘not only as a result of one’s own acts or omissions, but also of those

of such persons for whom one is liable.’ This includes parents being liable for the

harm caused by their children; guardians being liable for damages caused by minors

or incapacitated individuals under their supervision; owners or managers of a

company being liable for damages caused by their employees in the exercise of

employee functions; and teachers and schools being liable for damages caused by

students under their control during school and extracurricular activities. This rule

does not attach strict liability on the injurers or their supervisors,

7

as liability only

arises because the supervisors are presumed to have failed in their duties to

properly supervise, educate, or control those under their authority or control. In

other words, under Spanish law, defendants face a rebuttable presumption of

negligence. As specified by the last para of Art 1903 of the Spanish Civil Code,

8

to

avoid liability, a defendant must establish that he or she acted with the same

diligence as that of a reasonable person (‘a good family man’), although the

undertaken precautions did not suffice to prevent the accident.

As discussed above, the drafters of Arts 1384, 1385, and 1386 of the code

Napoléon initially took an intermediate position between a rule of strict liability

and a rule of presumed liability. The code also had a clear influence on the rules

introduced in Italy. Arts 1153–1156 of the Italian Civil Code of 1865 represent a

mere transplant of the French rules into the Italian system. Presumptions of

negligence are found in similar set of tort cases under Arts 2047, 2048, 2050, and

2054 of the Italian Civil Code of 1942. Unlike France, under both codifications,

Italian courts interpreted these presumptions as rebuttable from their initial

applications. Under Art 2047, para 1, of the Civil Code, in the event of damage

caused by an individual lacking legal capacity, the supervisor or guardian of the

individual becomes liable for the harm, unless they are able to prove that they

could not have prevented the harmful act.

9

According to Art 2048, the parents or

Traitè des obligations en génerale (Paris: Rousseau, 1925), 983; R. Savatier, Traitè de la responsabilité

civile en droit français (Paris: Librairie générale de droit et de jurisprudence, 1951), 421; H. Lalou,

Traité pratique de la responsabilité civile (Paris: Dalloz, 1962), 665. On liability for risk, see n 7

below.

7

See Arts 1905, 1908 and 1910 of the Spanish Civil Code.

8

Art 1903 of the Spanish Civil Code: ‘The liability provided in the present Article shall cease

if the persons mentioned therein provide evidence that they acted with all the diligence of an

orderly [good family man] to prevent the damage.’

9

Art 2047 Civil Code. According to Corte di Cassazione 26 January 2016 no 1321, in order

to be held not liable, it is necessary that the duty of care (of supervision), and its related liability,

be transferred to another subject by contract, by law, or some other mechanism. For the

presumption of liability provided by Art 2047 Civil Code, regarding who is liable for watching

81 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

guardians are liable for civil wrongs committed by non-emancipated minor children

or persons subject to their guardianship and who live with them.10 Moreover, para

2 states that teachers and those who teach a trade, art, or profession are liable for

any tort damages caused by their students or apprentices occurring while under

their supervision.

11

Under para 3, such teachers are exempted from liability if they

prove that they acted diligently or would have been unable to prevent the act.

12

In analyzing these topics, the literature frequently focuses on whether these

provisions operate as a rule of presumed negligence or, de facto, as one of strict

liability. The effects of a presumption of negligence can be seen in the concept of

imputed risk contained in these provisions and their wording. Liability can be

avoided on two interrelated grounds. First, the presumption can be overcome by

showing that due care was exercised in supervising the injurer and that the accident

occurred, notwithstanding the adoption of diligent precautions. Second, the

provisions explicitly allow for the parent or teacher who failed to take due care to

show that, even if they had taken reasonable precautions, they would not have

been able to prevent the accident. In this case liability can be avoided on causation

grounds, even in the shadow of the unrebutted presumption of negligence. In

other words, even if the supervisor had acted diligently, the accident could not have

been avoided.

13

A similar argument applies with respect to presumed culpa in

vigilando and presumed culpa in educando. According to Italian case law, to

rebut the presumption of negligence, the parent must prove that he has properly

educated and adequately supervised the child based on their age, character, and

nature (which in turn is a function of the environment, attitudes, and personality

of the child).

14

Short of that proof, the parent can still avoid liability on causation

grounds, demonstrating that a proper education and supervision would not have

been sufficient to prevent the accident.

over an unable person and for the admissibility of liability against the healthcare provider, see

Corte di Cassazione 20 June 2008 no 16803. According to Corte di Cassazione 12 December

2003 no 19060, the recovery of a firearm used as a toy by incapable children does not constitute

an exceptional and unforeseeable fact suitable to excuse a parent’s liability under Art 2047 Civil

Code, since the supervision of the incapable child must be constant and uninterrupted as well as

not occasional nor from a distance.

10

Art 2048 Civil Code.

11

ibid para 2. According to Corte di Cassazione 18 September 2015 no 18327, a parent’s

liability for the tort of the minor child exists pursuant to Art 2048 Civil Code and is not excused

even when the harmful behavior of the child was carried out in a place subject to the supervision of

others. For references regarding presumed liability, see generally Corte di Cassazione 22 April

2009 no 9542, Massimario Giustizia civile, 663 (2009); Corte di Cassazione, 20 October 2005

no 20322, Massimario Giustizia civile, 1919 (2005); Corte di Cassazione 28 March 2001 no

4481, Massimario Giustizia civile, 607 (2001).

12

Art 2048 Civil Code. See M. Franzoni, ‘Fatti illeciti’, in A. Scialoja and G. Branca eds,

Commentario al codice civile, Libro quarto: Obbligazioni, Art. 2043-2059 (Bologna-Roma:

Zanichelli, 1993), 326, 347, providing a detailed analysis of case law.

13

G. Alpa, Responsabilità civile e danno. Lineamenti e questioni (Bologna: il Mulino, 1991),

303.

14

See ibid 304-305, for references to cases.

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 82

Legal presumptions of negligence are also present in Germany. The German

BGB of 1900 adopted the so-called binary system of legal presumptions:

‘this expression indicates all the various types of cases in which the

person is faced with liability not based on negligence deriving from an action or

omission, but rather grounded on a rebuttable presumption of negligence or,

at times, liability without negligence…’

15

This latter category includes cases of vicarious liability, where the principal is

liable for the harm caused by his agents in the performance of an activity. The

principal can avoid liability by proving that he used reasonable care in the choice

and supervision of the agent, or if the damage would have resulted even if

reasonable care had been exercised.

16

Similarly, supervisors of minors and legally

incapacitated individuals are liable for the harm caused by individuals subject to

their supervision, unless they can prove that they diligently fulfilled their duty of

care.

17

This second category also includes the liability of an animal’s owner and

keeper. An animal owner, under § 833 must compensate any individual who is

killed or injured by their animal, regardless of whether they exercised reasonable

care.

18

Under § 834, this provision is also applicable to those who supervise the

animal by contract for the owner.

19

Similarly, under §§ 836– 837, whoever owns

or possesses property is liable for any harm caused by the collapse or destruction of

a building or any other structure on the land, unless the owner or possessor proves

that they exercised due care in preventing the risk of damage.

20

2. Presumed Negligence Rules for Enterprise and Motor Vehicle

Liability

At the end of the nineteenth century, in some European legal systems, we

observed a gradual transition from negligence-based models of liability to models of

liability based on the notion of ‘risk creation.’ Legal academics belonging to the so-

called ‘legal socialism’ movement in Italy and France

21

denounced the failure of

negligence as a general foundation of liability and developed what became

15

G. Alpa, n 4 above, 304.

16

BGB § 831.

17

ibid § 832. Note that in 1999, the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB) was reformed. Liability for

obligations arising for minors was restricted. The new § 1629a provides that the financial liability

for transactions concluded before the eighteenth year by the legal representatives of the minor

(or personally by the minor with the consent of the legal representatives) is limited to assets that

exist upon reaching the age of majority. The limitation does not apply to liability coming from

wrongs committed by the minor. M. Löhnig and D. Schwab, ‘La legge sulla limitazione di

responsabilità del minore’ Responsabilità civile e previdenza, 1215 (2000).

18

ibid § 833.

19

ibid § 834.

20

ibid §§ 836-837.

21

See P. Ungari, ‘In memoria del socialismo giuridico’ Politica del diritto, 248 (1970); A.

Loria, ‘Socialismo giuridico’ La scienza del diritto privato, 519 (1893).

83 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

known as the ‘risk theory of profit’.

22

The idea centered on the premise that the

risk generated by a firm through its economic activity is a risk that needed to be

considered as a cost of production. Theories of liability that were developed based

on the risk theory of profit reframed negligence liability by creating a presumption

of liability on the person who generated the risk, unless proven otherwise.

23

This

intellectual evolution led to the paradigms of strict liability or semi-strict liability

and the broader use of legal presumptions of negligence.

From a functional perspective, rules of presumed negligence should not be

confused with the Common law doctrine of res ipsa loquitur. Under the rule of

res ipsa loquitur, courts depart from the traditional presumption of non-negligence

because the facts are so obvious that requiring parties to argue any further would

be redundant and contrary to procedural economy.

24

This principle of law, also

known in Germany as prima facie-Beweiss, is particularly widespread in other

civil law systems: the fact that a harm has occurred provides prima facie evidence

of the wrongdoer’s negligence.

25

In several European jurisdictions, drivers of vehicles not guided by rails (ie,

vehicles other than trains), are presumed negligent and thus face semi-strict

22

For a presentation of the legal socialism movement and the risk theory of profit developed by

A. Loria, see G. Frezza and F. Parisi, Achille Loria (1847-1943) (Elgar Companion to Law and

Economics, J.G. Backhaus ed, 1999), 392–402.

23

M. Philonenko, ‘Faute et risque créé par les énergies accumulées’ Revue trimestrielle de

droit civil, 305 (1950).

24

See A. Guerra, B. Luppi and F. Parisi, ‘Do Presumptions of Negligence Incentivize

Optimal Precautions?’ 53 European Journal of Law and Economics, 511-533 (2022). According

to the exemplary quote of Chief Justice Erle, ‘there must be reasonable evidence of negligence.

But where the thing is shown to be under the management and control of the defendant or his

servants, and the accident is such as in the ordinary course of things does not happen if those

who have management use proper care, it affords reasonable evidence, in the absence of

explanation by the defendants, that the accident arose from want of care.’ Scott v. London & St.

Katherine Docks Co. (1865) 159 Eng. Rep. 685; see also Byrne v. Boadle (1863) 159 Eng. Rep.

299, 300–01. In the US, a minority of states find that res ipsa loquitur creates a presumption of

negligence, including California and Colorado. See, eg, Blackwell v. Hurst, 54 Cal. Rptr. 2d 209

(Cal. Ct. App. 1996); Stone’s Farm Supply, Inc. v. Deacon, 805 P.2d 1109 (Col. 1991).

25

See P.G. Monateri, La responsabilità civile. Le fonti delle obbligazioni (Torino: UTET,

1998), 11; V. Fineschi, ‘Res ipsa loquitur: un principio in divenire nella definizione della responsabilità

medica’ Rivista italiana medicina legale, 419 (1989). Along these lines, the Italian Supreme Court

affirmed that ‘in matters of tort liability, it is up to the plaintiff, who sues for damages, to put

forth evidence of the injurer’s negligence; this principle, however, does not necessarily imply that

the judge requires negligence be proven exclusively from the evidence offered by the injured party,

as the proof can be inferred from the facts and circumstances of the specific case. The evidence

can also be presumptive, and, in this regard, a fact can be inferred circumstantially due to the id

quod plerumque accidit rule, taking into consideration that it is not always easy to acquire direct

evidence.’ That specific case dealt with products liability, and more specifically, involved a bottling

company sued for damage caused by the bursting of a bottle containing a carbonated beverage.

Corte di Cassazione 28 October 1980 no 5795; G. Monateri, above, 111. There is no general rule

that indicates when it is possible to apply res ipsa loquitur or other presumptive inferences based

on the id quod plerumque accidit because they are called upon to operate based on circumstantial

evidence and findings of the specific case. ibid 114.

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 84

liability for any harm caused to people or things while operating the vehicle,

unless the driver or operator is able to prove that he has undertaken reasonable

precautions to avoid the harm.

In the field of traffic accidents, Germany adopted a mix of strict liability and

presumed negligence rules, as early as 1909. Specifically, the Liability Provisions of

§ 7 of the German Road Traffic Act (Strassenverkehrsgesetz, hereinafter StVG)

provides the central rule establishing a form of semi-strict liability for the owner

or keeper (eg, lessor) of a motor vehicle, for the damage caused by the operation

of the vehicle killing, injuring, or creating material damage to third parties. In

such cases, liability can only be avoided showing that the accident was the result

of force majeure, or the vehicle was used without the knowledge and permission of

the owner.

26

When the driver is not the owner, the Traffic Act introduces a second

ground for avoiding liability under § 18 StVG, allowing the operator to prove that the

loss was not due to his or her fault.

27

Under this rule, liability can be avoided also

by the owner and the keeper by showing that due care was exercised or that the

accident was not caused by the failed adoption of diligent precautions.

28

Under

the German Traffic Act § 17, when an accident occurs between two motor vehicles, a

rule of presumed liability applies. In such cases, liability is apportioned according to

the circumstances and the principles of comparative negligence and can only be

entirely avoided by the parties by proving they have acted with due care.

29

3. Presumed Joint Negligence Rules

The Italian rules presuming negligence in traffic accidents are a bit more

elaborate, leaving less room for discretionary evaluations based on the circumstances

of the case if parties cannot prove to have acted with due care. Art 1156 of the

Italian Civil Code of 1865 introduced, for the first time, joint liability for torts

ascribable to more than one person. Based on this rule, the current civil code

uniquely applies joint liability for vehicles coupled with a presumption of negligence.

Italy’s regime resulted in a novel legal rule, creating a legal ‘presumption of joint

negligence’ for accidents between motor vehicles.

30

This interesting spin on legal

26

See § 7 StVG: ‘If a person is killed or injured or material damage incurred from the

operation of a motor vehicle, the owner of the vehicle is obligated to compensate the injured

party for the resulting loss, unless the accident was the result of force majeure, or the vehicle was

used without the knowledge and permission of the owner’.

27

§ 18 StVG: ‘In the cases of § 7(1), the operator is also liable to pay compensation pursuant

to §§ 8–15, unless the loss is not the fault of the operator.’ This amounts to a reversal of the

burden of proof (Beweislastumkehr) on the issue of negligence.

28

Van Dam (2013, 412) point out that German case law has found drivers not negligent

when they prove to have taken the level of due care of ‘the ideal driver who takes into account

the considerable chance that other people make mistakes.’ BGH 17 March 1992, BGHZ 117, 337;

BGH 28 May 1985, NJW 1986, 183.

29

Although not explicitly stating so, § 17 StVG de facto introduces a rebuttable presumption of

joint negligence, like the Italian rule of presumed joint liability discussed in the text.

30

G. Frezza and F. Parisi, Responsabilità civile e analisi economica (Milano: Giuffrè, 2006), 93.

85 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

presumptions specifies that in the event of a collision, unless proven otherwise,

parties are presumed jointly negligent. According to this rule, it is presumed that

each party equally contributed to producing the harm and is proportionally liable

to compensate for the harm suffered by each vehicle (ie each driver is presumed

equally negligent and liable for fifty percent of the damages caused).

31

As originally

written, this rule only applied when the collision resulted in harm to both vehicles.

The Italian Constitutional Court found this to be unconstitutional.

32

The

Constitutional Court stated that the presumption of bilateral negligence and the

resulting joint liability should also apply when only one of the vehicles has

suffered harm in the accident, indicating that the presumption of joint liability

was based on evidentiary principles, and was not created for the purpose of

spreading the accident loss between the parties.

33

The evidence needed to rebut the presumption of joint liability consists of

proving that the drivers undertook reasonable precautions to avoid the accident. To

avoid their share of liability, drivers must show that they obeyed all relevant

traffic rules and undertook reasonable precautions, under the circumstances of

the case.

34

Furthermore, Italian law includes a specific rule for the collision between

vehicles, both those moving and those temporarily parked.

35

In these cases,

concurrent liability of drivers is presumed until proven otherwise. In tort situations

involving two or more parties, each party is assumed to have contributed equally to

the accident, even when the vehicle was not moving. Each party bears the burden

of producing evidence. Paradoxically, the owner of the parked car may be in a

worse position to produce evidence, notwithstanding the fact that in most cases

a parked car is less involved in the causation of an accident.

If only one party can produce satisfactory evidence about their diligent behavior,

the other party is held unilaterally negligent and bears the entire loss, as injurer

(facing full liability) or as victim (facing the full loss, with no compensation).

When neither party can prove his or her diligent behavior, the Italian rule leads

to a sharing of the loss, like a rule of comparative negligence. Liability increases

31

Art 2054 civil code. For an articulated analysis of applicable case law, see generally M.

Franzoni, n 12 above, 326-347. According to Corte di Cassazione 23 October 2014 no 22514, the

principle stated by Art 1227 civil code (also applicable to tort law due to the express reference

contained in Art 2056 of civil code) of the proportional reduction of damage based on the

percentage entity of the causal efficiency of the injured party applies not only to the injured party,

which claims compensation for the harm directly suffered, but also against the relatives who, in

relation to the reflected effects on them, start legal action in order to be redressed for the damage

suffered iure proprio.

32

Corte costituzionale 14 December 1972 no 205.

33

ibid

34

Corte di Cassazione 19 September 1980 no 5321; Corte di Cassazione 21 June 1979 no

3443. Additional discussion can be found in G. Spina, ‘L’accertamento della responsabilità da

sinistro stradale nella recente giurisprudenza. Profili sostanziali e giurisprudenziali’ Responsabilità

civile e previdenza, 1806 (2014).

35

G. Alpa, n 3 above, 711.

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 86

and decreases in relation to the extent of the proven negligence of the driver.

36

When both parties can prove their diligent behavior, each party bears the loss

suffered in the accident and no liability or compensation is owed to one another.

Other European legal systems, including the Netherlands introduced rules of

presumed liability, creating rebuttable presumptions of negligence against injurers.

In the Netherlands, however, a stronger presumption applies in favor of victims

of motor vehicle accidents. Art 185 (1), Wegenverkeerswet (Road Law), 1994:

‘If a vehicle driven on the road is involved in a road accident, causing

damage to persons or things (not to another motor vehicle), the owner or

keeper of the vehicle is liable to compensate the harm, unless he can be

proved that the accident was due to force majeure or by a person, for whom

the owner or the keeper are not responsible.’

According to these European rules of presumed liability, evidence of harm and

causation are sufficient elements to establish liability, effectively shifting the

burden onto the defendant to show that he behaved diligently. Thus, in the event

of an accident, injurers are by default liable and must pay full compensation unless

they can rebut the presumption by proving their own diligence or showing that the

victims’ behavior was itself negligent or not foreseeable, or that the accident was

somehow not avoidable.

Other countries are debating a change from the conventional presumption

36

According to Tribunale di Catania 7 May 2020 no 1497, ‘the concrete ascertainment of

the fault of one of the drivers does not involve the overcoming of the joint liability presumption

of the other if the latter has not concretely provided satisfactory evidence relating to the lack of

any possible charge against him’. Tribunale di Grosseto 7 May 2020 no 324 believes that in car

accidents, para 2 of Art 2054 of the Italian Civil Code provides a presumption of liability for both

drivers of vehicles involved in an accident. In this regard, the aforementioned rule does not constitute

a strict liability hypothesis for the driver, but rather one of presumed liability. The driver can

overcome this presumption by proving that he has done everything possible to avoid the damage,

or by demonstrating sufficient diligence, ie, behavior free of negligence and in compliance with the

traffic laws, as evaluated by the judge accounting for the circumstances of the specific case. In this

sense, the presumption of negligence has a merely subsidiary function and operates only when it

is impossible to determine the concrete extent of the respective liabilities. In other words, if the

negligence of one driver is ascertainable, the other driver is exempt from the presumption of

liability and is not required to prove that he has done everything possible to avoid the damage.

According to the Tribunale di Pisa 25 March 2020 no 354, the first para of Art 2054 of the Italian

Civil Code contemplates a form of presumed liability that can be overcome by the driver proving

that he has done everything possible to avoid the damage. For example, if a driver strikes a pedestrian

outside of a crosswalk, then the driver may avoid joint liability by demonstrating that the

pedestrian failed to give the driver the right of way, resulting in an unforeseeable and inevitable

obstacle, and that the driver had otherwise behaved correctly. According to Corte di Cassazione

20 marzo 2020 no 7479, on the subject of a collision between vehicles, the presumption of joint

liability established by Art 2054, para 2, of the Civil Code has a subsidiary function, operating only

in the event that the evidentiary findings do not allow to ascertain in a concrete manner to what

extent the conduct of the two drivers caused the damage and to allocate the actual liability for the

accident (in the specific case, two different technical experts were not allowed to reconstruct the

exact dynamics of the accident).

87 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

of non-negligence to presumed liability in various tort situations.

37

The push to

shift the burden of proof from victims to injurers is advanced on several grounds.

One argument is that a shift in the burden of proof would provide protection to

more vulnerable road users, such as cyclists (in accidents with motorcycles, cars,

trucks, etc) and pedestrians (in accidents with cyclists, motorcycles, cars, trucks,

etc), as well as victims below the age of sixteen and over seventy and disabled

individuals. Advocates say these rules are needed for both fairness and efficiency

reasons. Another argument is that the shift in the burden of proof onto the injurer is

fairer than the standard fault-based evidence rule, as it shields more vulnerable

victims from the burdensome task of proving the negligence of their injurer.

38

Yet

other arguments in support of the presumption of negligence point to the

widespread availability and rapid development of new evidence technologies,

such as helmet cameras, black-box technology, and GPS location technologies,

which make it easier for injurers to record accident events and provide evidence

to rebut a presumption of negligence.

As will be discussed below, a jurisdiction’s choice of which party should bear the

burden of proof can have a significant impact on the parties’ tort incentives, as

well as on their incentives to invest in private evidence. Given the new range of

evidentiary technologies, the choice of legal presumptions would benefit from a

broader reassessment. In Section 3, we will offer a broad-brush outline of some

of the relevant considerations, which we frame under the general umbrella of the

‘cheapest-evidence-producer criterion.’

III. The Effect of Legal Presumptions on Tort Incentives

As pointed out by Castronovo, presumptions of liability in contemporary

legal systems are

‘a dogmatically heterogeneous category because they combine the

presumption, that is a qualification of the fact, with the resulting liability,

that is a judicial effect.’

39

While the policy rationales and theoretical foundations of the presumptions of

negligence vary greatly across jurisdictions—from simple inversions of the burden

of proof for procedural economy or fairness, to goals of risk-spreading between

the parties, to other policy objectives—the legal and economic consequences of

37

In the UK see the Parliamentary debate 24 March 2011, Parl Deb HC (2011) col. 1222 W

81 (UK).

38

R.H. Grzebieta, J. Olivier and S. Boufous, ‘Reducing the Rate of Serious Injuries to

Cyclists’ Medical Journal of Australia, 242 (2017); S. Boufous, ‘It Is Time to Consider a Presumed

Liability Law that Protects Cyclists and Other Vulnerable Road Users’ 28 Journal of the Australasian

College of Road Safety, 65 (2017).

39

C. Castronovo, ‘Sentieri di responsabilità civile europea’ Europa e diritto privato, 797 (2008).

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 88

these presumptions are straightforwardly uniform: when there is a lack of evidence

pertaining to the relevant facts that led to an accident, a shift in legal presumptions

turns a case that would have favored the defendant into a case favoring the plaintiff

(or a splitting of the loss, under the Italian rule of presumed joint negligence for

motor vehicle accidents).

40

1. Effects of Presumptions of Negligence Under Alternative Liability

Regimes

Shifts in burdens of production of evidence are not neutral to truth-finding.

Shifting the burden from one party to the other unavoidably affects the parties’

respective probabilities of success in litigation. To the extent to which the case

has one objective truth, the fact that the burden of proof affects the parties’

likelihood of success in litigation must also imply that shifts in the burden will

affect the probability that one or another type of judicial errors (Type-I or Type-

II) takes place. Think of automobile accidents. A presumption in favor of defendant

reduces the probability of imposing liability on a negligent driver, while a

presumption in favor of plaintiffs increases the probability of imposing liability

on a non-negligent driver.

The effects of these errors are not only distributive.

41

Besides the obvious

desire to reduce the frequency of judicial errors, it is also important to consider

the effect that different types of errors may have on tort incentives.42 The associated

social cost may differ, given the effects of these errors on the incentives of prospective

injurers and prospective victims. When parties expect probatory difficulties, legal

presumptions shift care incentives from one party to another.

When shielded by a presumption of non-negligence in their favor, injurers

may strategically rely on their victims’ difficulty in satisfying their burden of proof.

This may dilute their precautionary care incentives. As probatory difficulties increase,

a negligence ruler with a non-negligence presumption gradually degenerates into

a no liability rule, entirely diluting potential injurers’ care incentives. The adoption

40

See G.A. Micheli et al, L’onere della prova (Padova: CEDAM, 1942), 313.

41

There is nothing deterministic about the optimal allocation of the burden of proof in the

face of the possible judicial errors. By shifting the burden from one party to the other, the

probability of error also shifts from one party to the other party. For example, a presumption in

favor of the defendant (like the traditional negligence rule) may give him an advantage and lead

to a margin of error in his favor (a fraction of cases may be erroneously decided in favor of the

defendant when the plaintiff is unable to prove the negligence of his injurer). The adoption of a

presumption in favor of the plaintiff, however, creates a mirror-image problem, giving the

plaintiff an evidentiary advantage that may lead to a margin of error in his favor (a smaller or

larger fraction of cases may be erroneously decided in favor of the plaintiff when the defendant

is unable to prove his diligence).

42

As pointed out by R. Cooter, D. Robert and A. Porat, ‘Does Risk to Oneself Increase the Care

Owed to Others? Law and Economics in Conflict’ 29 Journal Legal Studies, 19-34 (2000), prospective

victims will not necessarily act differently depending on the legal liability rule-prospective victims

who are already facing substantial risks of serious personal injury that vary with the degree of care

that they take, are not affected by changes in liability rules, except in very rare cases.

89 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

of legal presumptions of negligence could correct this problem. When faced with

a presumption of negligence, probatory difficulties shift the expected accident loss

on injurers. As probatory difficulties increase, a negligence rule with a presumption

of negligence gradually degenerates into a rule of strict liability, inducing injurers to

undertake efficient care. The choice of presumptions of negligence can thus be

desirable to mitigate the diluting effects of judicial errors on injurers’ tort incentives.

However, the same reasoning applies with respect to the legal presumptions

applicable to victims. When shielded by a presumption of non-negligence in their

favor, prospective victims may strategically rely on their injurers’ difficulty in proving

their contributory or comparative negligence, and this may dilute the victims’ care

incentives. As probatory difficulties increase, the incentives created by a defense

of contributory or comparative negligence may gradually disappear entirely. The

adoption of legal presumptions of joint negligence, like those adopted in some

European jurisdictions for traffic accidents, corrects this problem. When faced with

a presumption of joint negligence, probatory difficulties shift the burden of proof

back on victims. As probatory difficulties increase, prospective victims will fear being

barred from receiving full compensation, inducing them to undertake efficient

care.

43

The adoption of presumptions of joint negligence can thus be desirable to

mitigate the effect that judicial errors may have on both victims’ and injurers’ tort

incentives.

A second effect of legal presumptions and discovery regimes is on the parties’

activity levels. As discussed above, in a world of imperfect adjudication, a shift of

the burden of proof also transfers the cost of legal errors. A change in legal

presumptions would affect the cost and desirability of a given activity, due to the

shift in expected liability associated with the ability to satisfy the burden of proof.

More specifically, a presumption that shifts the burden towards the defendant

increases the expected cost of the defendant’s activity. This is because, in the event

of an accident, the defendant will have to incur the cost of producing evidence, or

bear the liability associated with his inability to produce evidence (even when his

behavior was non-negligent).

The costs associated with the burden of proof can be analogized to a tax

imposed on the risk-generating activity. This tax will reduce the optimal level of

activity for the party facing the burden of proof. Those familiar with the economic

analysis of tort law will soon realize that this effect could be a curse or a blessing,

depending on which party bears the burden.

44

This is because the burden of

43

For a formal analysis of the effects of legal presumptions on care incentives in the presence of

judicial errors, see A. Guerra, B. Luppi and F. Parisi, n 24 above.

44

As per Shavell’s activity level theorem, no negligence-based regime can incentivize

optimal activity levels for both parties. This is because the party who does not bear the residual

liability is only concerned about avoiding liability by undertaking due care and does not internalize

the additional cost of non-negligent accidents. Conversely, the bearer of residual liability wants

to avoid harm altogether and will be incentivized to undertake both optimal care and optimal

activity level. The cost imposed by the burden of proof can therefore do either of two things: sub-

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 90

proof imposes a tax on activity level which can alternatively distort the already

optimal incentives of the residual bearer or mitigate the inefficiently high activity

levels of the party who does not bear the residual loss. The optimal use of the

burden of proof as an activity level tax requires the creation of a legal presumption

in favor of the party burdened with the accident loss when both parties acted

diligently. This would entail imposing the burden on the defendant when the dispute

arises under negligence-based regimes (ie, simple negligence, negligence with

contributory negligence, or negligence with comparative negligence) and instead

shifting the burden on the plaintiff when the dispute arises under strict liability

regimes (ie, strict liability with contributory negligence, or strict liability with

comparative negligence). Accordingly, the European rules of presumed joint

negligence create a desirable alignment of incentives, bringing the activity levels

of both parties closer to the socially optimal levels.

2. The Negative-Proof Problem and the Role of Evidence Technology

One of the common explanations for the use of presumptions of non-

negligence and the allocation of evidentiary burdens on plaintiffs (in establishing the

fault of their injurers) is that if plaintiffs did not have the burden, there could be

an increase in potentially litigation, including a substantial fraction with little

merit, brought to extract settlements from defendants. In the absence of fee-shifting

rules or other correctives against frivolous claims, defendants might settle a case

for a positive amount to avoid having to spend a greater amount proving that they

were not negligent. The availability of new evidence technologies has reduced the

cost of evidence production and the reliability of the evidence produced by

defendants who invested in due care, weakening the practical rationales for the

adoption of presumptions of non-negligence in tort cases.

Further, the availability of new evidence technologies has mitigated a theoretical

and practical objection that was frequently raised against the use of legal

presumptions of negligence. The objection consisted in the fact that a burden placed

on the defendant would often entail a negative proof and would de facto deteriorate

into a semi-strict or strict liability rule. The procedural laws of evidence were

traditionally viewed as embracing this basic principle by allocating the burden of

proof on plaintiffs; shifting the burden of proof on the person denying an assertion

or a claim would constitute a logical fallacy, creating a presumption of truthfulness

of the claim unless otherwise disproven. According to this principle, the victim

optimally reduce the activity levels of the residual bearer or mitigate the excessive activity level

incentives of the non-residual bearer. Shavell’s proposition has become known in the law and

economics literature as ‘Shavell’s activity level theorem.’ See F. Parisi, The Language of Law and

Economics: A dictionary (Cambridge: University Press, 2013) for the standard restatement of this

theorem. An ideal remedy in tort law should instead incentivize optimal precautionary care levels and

optimal activity levels for both parties. S. Shavell, ‘Strict Liability Versus Negligence’ 9 The Journal of

Legal Studies, 1 (1980), showed that this ideal is not achievable under negligence-based regimes,

because only the bearer of residual liability will have incentives to mitigate its activity level.

91 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

should bear the burden of proof of the elements of negligence necessary to establish

the injurer’s liability, because shifting the burden of proving the non-existence of

those elements on the injurer would reproduce the same logical fallacy. By

creating a presumption of negligence, the injurer would face the formidable burden

of proving a negative—the lack of negligence on his part. This would create a

presumption of truthfulness of the tort claim, unless successfully disproven by

the defendant.

The implicit premise of this argument is that negations often involve universal

negatives, while affirmations do not. The proof of a universal negative is what

ancient Romans called probatio diabolica (literally, ‘devil’s proof’), to signify its

heinous difficulty. Consider, as an example, the allegation of a fact: ‘Defendant

signed a contract promising X.’ A signed document and a few additional pieces

of corroborating evidence would suffice to establish such an assertion. On the

contrary, the negative claim by defendant ‘I have never signed a contract promising

X’ would entail the proof of a universal negative, necessitating omniscience and

omnipresence on the part of the defendant, and ultimately requiring the

examination of a potentially infinite amount of evidence by the factfinder.

Despite its logical soundness, in today’s world, the negative-proof argument

presents a more limited logical objection to the use of legal presumptions of

negligence. Consider the case of a negligence tort. Contrary to the example used

to illustrate the negative-proof fallacy, proving the non-negligence of the injurer

at the time of the accident (or, for this matter, proving that any other element of

the tort is not present) does not entail the proof of a universal negative requiring

omniscience and omnipresence-proving non-negligence amounts to proving due

diligence.

The logical foundations of the law of proof do not dictate that in this case the

burden of proof should necessarily be placed on the plaintiff making an assertion

or a claim.

45

While at times it may be easier for a plaintiff to prove the negligence

of the defendant, in other situations it may be easier for a defendant to prove his

own diligence. Neither type of proof requires supernatural abilities. The choice of

an optimal allocation of the burden of proof in these cases hinges upon a test of

comparative advantage in the access to relevant information. Ceteris paribus, when

the factual premises of the negative-proof argument do not hold, the party who

has a comparative advantage in providing truthful evidence (hereinafter, the

‘cheapest evidence producer’) should bear the burden of proof.

45

The inapplicability of the philosophical constructs to the legal notions of burden of proof and

choice of legal presumptions was pointed out in the early 1930s by Columbia law professor

Jerome Michael and Chicago philosopher and law professor Mortimer Adler, who observed:

‘The principles of logic do not place upon either party any burden of proving the propositions

which they have respectively alleged. The principles of logic are concerned only with the validity

and the structure of the processes by which proof and disproof are accomplished.’ M. Adler and J.

Michael, The Nature of Judicial Proof: An Inquiry into the Logical, Legal, and Empirical Aspects of

the Law of Evidence (New York: Colombia Law Review, 1931), 60.

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 92

The test of comparative advantage is informed by some general assumptions

and guiding rules of thumb. For example, when the standard of due care entails

the undertakings of many actions, proof of diligence can be more burdensome than

the proof of negligence. Proof of negligence could be satisfactorily obtained by

showing that any one of the required actions had not been undertaken. Proof of

diligence would instead require evidence that each and every required precautionary

action was undertaken. In the limiting case in which an infinite number of actions

need to be undertaken to satisfy due care, a negative proof of non-negligence

would become virtually impossible. Thankfully, no such infinite list of burdensome

duties of care is legally expected from ordinary humans.

46

If, as it seems, there is nothing fundamentally necessary behind the idea of

placing the burden of proof on plaintiffs, the next logical question becomes

identifying the factors that should drive the optimal allocation of the burden of

proof. On this matter, it is important to consider that new technology is substantially

increasing the amount of information that can be acquired and preserved, with

far-reaching applications in the field of legal evidence and discovery. Scientific

and technological innovations play a dual role in evidence and discovery. Some

technologies can give factfinders insights, allowing them to look back and gather

information about past events, while others record and preserve present information

for future uses. We shall refer to the first group as ‘investigative technologies’ and

to the second group as ‘fact-keeping technologies.’

1. Investigative Technologies. The characteristic feature of investigative

technologies is that they can be employed ex post even though no such technology

was used or available at the time of the event. Consider, for example, evidence

obtained through genetic testing. Like a lie detector, genetic testing can shed light

on past events. This technology need not be adopted by the parties at the time of

the original event but instead can be deployed when a need for discovery arises

later.

2. Fact-Keeping Technologies. Other technologies collect information about

present events and preserve it for future investigations. This category encompasses

two subgroups. The first is technology that can be adopted by parties who are

neither prospective injurers nor victims, including local governmental authorities,

such as traffic surveillance cameras and satellite imaging, capable of documenting

facts and events that occur within their range. We shall refer to them as ‘public

fact-keeping technologies.’ The second involves technologies that individuals and

firms can privately adopt. These are instruments that are tailored to a specific set

of applications, determined by their user. Examples that fall within this category

include adoption of black-box technology on vessels, cameras on body vests or

helmets, Snapshot

®

and dash-mounted cameras on cars, use of digital timestamp

46

For a collection of cases describing the innumerable list of duties that a ‘reasonable man’

should fulfill to avoid being held negligent in torts, see the humorous book by A.P. Hebert,

Uncommon Law (London: Methuen, 1937), 3–11.

93 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

certification methods, use of electronic tamper-proof data storage systems

managed and certified by third parties, and various applications of GPS technology.

We shall refer to them as ‘private fact-keeping technologies’. Private fact-keeping

technologies consist of two distinct subgroups, each with different focuses and

applications. Some technologies, such as black-box technology, Google Timeline®,

Snapshot®, and cloud data storage, are better able to track the user’s own actions.

We shall refer to them as ‘first-party evidence technologies.’ Other technologies,

such as private surveillance cameras, fingerprints and face recognition devices,

are better able to document the activity of others. We shall refer to them as ‘third-

party evidence technologies.’

As will be discussed below, these evidence technologies have changed the

relative cost and reliability of providing evidence in a court proceeding, and thus

altered the resulting optimal allocation of burdens of production under the cheapest-

evidence-producer criterion.

3. Accuracy of Tort Adjudication and the Effects of Adversarial

Discovery

As Alice Guerra and Francesco Parisi pointed out, much of the conventional

wisdom underlying the choice of legal presumptions rests on the now-outdated

assumption that the amount of evidence available in any given situation (eg, the

number of witnesses or the amount of physical evidence available after an

accident) is not controlled by the parties. The advent of new evidence technology has

radically changed this situation. Individuals involved in a prospective accident

can endogenously control the amount of available evidence with the adoption of

evidence technology.

47

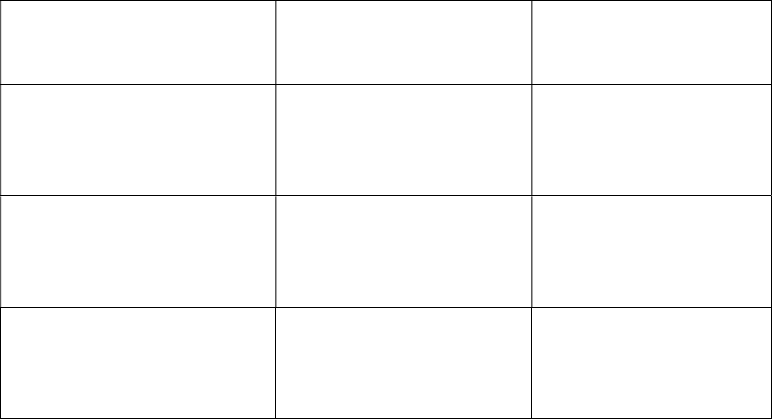

In this respect, legal presumptions influence the type of evidence technology

likely to be adopted. As summarized in Table 1 below, under traditional presumptions

of non-negligence, prospective injurers have limited incentives to invest in first-

party evidence technology, since in the event of an accident, it would primarily be

the victims’ burden to come forth with the necessary evidence. Prospective victims

would instead have incentives to adopt third-party evidence technology to prove

the negligence of their injurers. The opposite would hold under legal presumptions

of negligence. In this case, prospective injurers would be more likely to adopt first-

party evidence technology, and victims would have fewer incentives to invest in

third-party evidence technology. Presumptions of joint negligence would, instead,

incentivize both parties to invest in first-party evidence technology. Under this latter

presumption, prospective injurers would prevalently adopt evidence technology

focused on themselves to prove their non-negligence, and prospective victims

would similarly adopt evidence technology focused on themselves to prove lack of

47

A. Guerra and F. Parisi, ‘Investing in Private Evidence: The Effect of Adversarial Discovery’

14 Journal of Legal Analysis, 657–671 (2021).

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 94

contributory or comparative negligence. Hence, both parties would have greater

incentives to adopt first-party evidence technology.

Table 1: Legal Presumptions and Adoption of Evidence Technology

Injurers’ Evidence

Technology

Victims’ Evidence

Technology

Presumption of Non-

Negligence

— Third-Party Focused

Presumption of

Negligence

First-Party Focused —

Presumption of Joint

Negligence

First-Party Focused

First-Party Focused

The availability of new evidence technology increases the verifiability of

diligent and/or negligent behavior, increasing the benefits of the owner’s investment

in precautions. Precautions decrease the probability of an accident, but also help

individuals prove their diligent behavior to avoid liability. By increasing the ex

post verifiability of the parties’ behavior, evidence technology reinforces the parties’

incentives to act diligently. An increase in evidence and accuracy of adjudication

will change the relative price of negligent versus non-negligent behavior. A burden

placed on the defendant increases the wedge between the payoffs in cases of

diligent versus non-diligent behavior. That is to say, the relative payoff of diligent

behavior over non-diligent behavior is increased, causing a substitution effect.

48

These investments may lead to desirable adjustments in the parties’ care investments.

Think, for example, of a motorcyclist fearing to harm pedestrians in a regime of

presumed negligence. In the event of an accident, the motorcyclist would have to

prove lack of negligence to avoid liability. Evidence technology could help him

satisfy the required burden of proof. The motorcyclist may thus put a dashcam on

his motorcycle to present footage of the accident in a courtroom. Evidence technology

renders past behavior more verifiable and increases the value of his investments

in precautions. This would strengthen the motorcyclist’s incentives to act diligently

48

As shown in the law and economics literature, for a sufficiently moderate cost of evidence,

this substitution effect should not be observed given the discontinuity of payoffs created by a

negligence standard.

95 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

and to undertake the due level of care, further reducing the probability that he

will find himself in the role of injurer in the event of an accident. The overall care

level incentives created by legal presumptions of negligence would be further

amplified by the adoption of presumptions of joint negligence. Under presumptions

of joint negligence, both parties would adopt technology that increase the value of

their care investments, making them more verifiable.

49

It should be further observed that evidence rules concerning discoverability

of evidence can play an important role in determining the parties’ decisions to

invest in evidence technology.

50

The differences between the rules governing

adversarial discovery in the United States and Europe are significant. In 1938,

the enactment of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in the United States gave

origin to one of the most far-reaching discovery systems in the world, authorizing

discovery into any matter that is not privileged which is relevant to the subject

matter of the case.

51

As Allen et al pointed out, in most litigation settings modern US

discovery rules make a fetish out of free access to all information, rendering most

of the available evidence discoverable.

52

As Subrin put it, the federal discovery rules

have opened the doors to ‘fishing expeditions’ through adversarial discovery, where

litigants are allowed access to documents and data of the opposing party for

exploratory reasons in the search for information that may strengthen their case

or weaken the case of their opponent.

53

Rules of civil procedure at the state level

have followed the federal example, introducing some limits on discovery only in

the interest of procedural economy.

The reach of adversarial discovery as practiced in the United States. is not

available in civil law jurisdictions. The non-adversarial procedural traditions of

49

It should be noted that better verifiability of facts reduces the variability in the outcome

of the results: court decisions will be correct more often. The increase in accuracy does not

necessarily affect the parties’ activity levels. The risk of being incorrectly found negligent, and

required to pay damages despite having taken care, does not will deter activities. The increased

variance in judicial outcomes also entails a counterbalancing hope of being incorrectly found

diligent, and required to pay no damages, despite not having taken due care. Unless we assume

that lack of accuracy in adjudication entails a systematic bias toward the incorrect finding of

negligence (with no offsetting dismissals in favor of negligent defendants), on average, courts’

unbiased inaccuracy would not affect expected liability and the resulting activity levels.

50

For a formal economic model, assessing the effects of discovery rules on the incentives

to invest in private evidence, see A. Guerra and F. Parisi, n above 47.

51

See US Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 26.

52

R.J. Allen et al, ‘A Positive Theory of the Attorney-Client Privilege and the Work Product

Doctrine’ 19 Journal Legal Studies, 359 (1990). US evidence law generally makes most of the

available evidence discoverable. See A.R. Miller and C.E. Tucker, ‘Electronic Discovery and the

Adoption of Information Technology’ 30 The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization,

217 (2014); R.S. Haydock and D.F. Herr, Discovery Practice (New York: Wolters Kluwer, 2016).

53

S.N. Subrin, ‘Fishing Expeditions Allowed: The Historical Background of the 1938 Federal

Discovery Rules’ 39 Boston College Law Review, 691 (1998). For example, in United States v

Microsoft, 87 F. Supp. 2d 30 (D.D.C. 2000), prosecutors used e-mails sent between Microsoft

executives to prove anti-competitive intent towards Netscape. For other examples of e-discovery, see

A.R. Miller and C.E. Tucker, n 52 above.

2023] Burdens of Proof in Establishing Negligence 96

Europe adopt a different approach in legal discovery, letting each party produce

the evidence that is available to them, with very narrow use of court-ordered

discovery of evidence.

54

These approaches are deeply entrenched in the civil law

tradition and echoed in current case law, as best exemplified by the rules and

cases governing adversarial discovery in Europe. A few representative examples

are offered below.

The relevant laws governing the discovery of evidence in France are Arts 10,

138, and 139 of the Code of Civil Procedure (‘Code de procédure civile’). Under the

French Code of Civil Procedure Art 10, parties may petition the court to order the

other party or third parties to produce evidentiary material, but the judge’s

decision to allow discovery is discretionary.

55

However, French judges do not allow

adversarial access to evidence for exploratory reasons, and only force production of

evidence in cases where the opposing party already has knowledge of the content of

the sought-after evidence and has no other means to prove its claim (eg, to obtain a

signed agreement that remained in possession of the opposing party).

56

The opportunity for adversarial use of evidence under the Italian Code of

Civil Procedure (‘Codice di Procedura Civile’) is even narrower. Art 670 allows

parties to seek sequestration of physical documentary evidence (now interpreted to

also include electronic, audio, and video evidence) that contains information

already known to the other party and that — if later admitted by the court — could

be critical for the resolution of the dispute.

57

The role of the sequestration,

reflected in Art 671, is purely conservative: evidence is placed in the trust of a

third party, and it is not given to the opposing party for the search of other

information that could help to corroborate their case. The admissibility of the

preserved evidence in court is governed by Art 210 of the Italian civil procedure

code. Italian case law—ranging from trial courts to a recent decision of the Italian

Supreme Court (‘Corte di Cassazione’)—has narrowly interpreted Art 210,

affirming that adversarial discovery is granted at the discretion of the judge, and

should not be granted as an instrument to aid a party in meeting its burden of

proof.

58

Case law restated that the content of the requested evidence should be

known and specified by the requesting party, and discovery should not be asked

54

European legal systems follow a more conservative approach with respect to adversarial

discovery of private evidence. See M.H. Redish, ‘Electronic Discovery and the Litigation Matrix’

51 Duke Law Journal, 561 (2001); G. Foggo et al, Comparing E-Discovery in the United States,

Canada, the United Kingdom, and Mexico, (London: McMillan, 2020). For extensive references, see

T.P. Harkness et al, ‘Discovery in International Civil Litigation: A Guide for judges’ Procedure,

Advocacy, Strategy and Tactics in Arbitration, 14 (2017).

55

G. Serge, F. Frederique and C. Cecile, Procèdure civile (Paris: Dalloz, 2009), 341-42, 341-52.

56

See J. El-Ahdab and A. Bouchenaki, Discovery in International Arbitration: A Foreign

Creature for Civil Lawyers? (Arbitration Advocacy in Changing Times ICCA Congress Series no

15, 2011), 65-117. Requirements on the petitioning party further limit the application and viability of

forced production petitions within the French legal system. P. Harkness et al, n 54 above.

57

For discovery practices in selected jurisdictions, see P. Harkness et al, above n 54.

58

Tribunale di Frosinone 18 April 2018 no 379; Tribunale di Grosseto 7 January 2020 no 8.

97 The Italian Law Journal [Vol. 09 – No. 01

for exploratory reasons.

59

If the requesting party fails to specify the exact content of

the document requested through adversarial discovery, the request should be

denied.

60

In 2016, the Italian Supreme Court reaffirmed this principle, highlighting

its rationale when it stated that

‘the purpose of discovery is not to help the party prove something that

he would not have been able to prove in the absence of the new information

acquired through discovery.’

61

The relevant rules governing the adversarial discovery of evidence in Germany

are found in the German Code of Civil Procedure (‘Zivilprozessordnung’). Like

its French and Italian counterparts, the German Code of Civil Procedure does not

offer procedures for pretrial discovery similar to those found in US jurisdictions, and

the German principle against the use of discovery for exploratory reasons is

upheld in case law.

62

Furthermore, under German law there is no general obligation

to produce documents to assist the opposing party in transnational litigation.

This procedural principle led Germany to introduce reservations in the ratification

of the Hague Service of Process Convention, which entered into force on 26 June

1979. In ratifying the Hague Convention, Germany introduced declarations and

reservations that excluded the application of Chapter II of the Convention. As a

result, in transnational disputes, Germany will not execute requests of pretrial

discovery of documents as known in the United States (according to Art 23 of the

Declaration).

The differences in the adversarial discovery of private evidence have obvious

consequences on the parties’ incentives to invest in evidence technology. Under

a fully discoverable evidence regime, keeping track of one’s actions makes the saved

information subject to being discovered and subpoenaed, and possibly used as

evidence by opposing parties in the event of a dispute. Under US evidence law,

private investments in evidence could thus have a backlash effect on the party

that invested in the technology.

63

As an example, think of a dashboard webcam

that can be installed in a car. If the information gathered by the dashcam could be

59

Tribunale di Spoleto 1 July 2019 no 461.

60

Corte d’Appello di Torino, 8 July 2019 no 1153.

61

Corte di Cassazione 15 March 2016 no 5091.

62

Federal Court of Appeals (BGH) 4 June 1992, NJW 1992, 3096, 3099.

63

F. Parisi et al, ‘Access to Evidence in Private International Law’ 23 Theoretical Inquiries

in Law, 77 (2022), use a simple analytical model to illustrate the effect of these procedural differences

on individuals’ incentives to invest in private evidence technology, suggesting that the tension

between the retrospective and the prospective effects of discovery of private evidence should be

considered in the allocation of probatory burdens and the design of evidence rules. The impact of

discovery practice on private information technology in the US has been widely documented in

the empirical legal literature. A.R. Miller and C.E. Tucker, n 52 above studied the effects of state

e-discovery rules on the adoption of electronic medical records by hospitals. The study suggests

that in states that adopt e-discovery rules, hospitals reduced the use of electronic records to limit