PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

25

Feature

Non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), also

known as confidentiality agreements,

are part of the diet of many in-house

lawyers. They require one party to keep

confidential certain information that is

disclosed in the course of a transaction,

and to use that information only for the

particular purpose for which it is dis-

closed. UK lawyers doing deals in other

jurisdictions are expected to turn NDAs

round without help from local lawyers.

This article identifies key issues for con-

sideration, and helps spot when a spe-

cialist should be called on to help when

dealing with Germany, France, Italy,

Spain and the US (New York, Delaware

and California law only).

It is generally the case, across all of the

jurisdictions examined in this article,

that an express NDA will take prec-

edence over any implied position under

the law. However, this will not always

be the case if the law imposes a higher

standard, or the NDA conflicts with

public policy. Equally, in an interna-

tional deal, an adviser’s choice of gov-

erning law may not always prevail.

It is therefore important to understand

the legal context in which information is

exchanged and in which any NDA will

operate.

Non-disclosure

agreements

Key issues in international deals

Peter Watts, Philipp

Grzimek, Marco

Berliri, Alex Dolmans,

Winston Maxwell,

Lorig Kalaydjian

and Ellie Pszonka

of Hogan Lovells

International LLP

highlight the main

areas to watch out for

in some key overseas

jurisdictions.

Artist: Neil Webb

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200

26

Feature

PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

Four key questions to consider are:

• Is the disclosure or use of informa-

tion subject to constraints beyond

the control of the person disclosing

the information (the discloser)?

• Absent an express agreement,

would the law constrain disclosure

or use of the information?

• Does the context or manner in

which information is shared create

an obligation?

• What is the impact of any express

agreement?

EXTERNAL CONSTRAINTS

A discloser should consider whether it is

already under legal duties when it deals

with information.

These duties may result from the opera-

tion of statute or regulation, such that

the information is inherently protected.

A specific UK example of this is infor-

mation covered by the official secrets

legislation (see “Additional protec-

tions” below). Similarly, information

constituting a trade secret is generally

protected under US common law and,

in California and Delaware, by the Uni-

form Trade Secrets Act.

Personal data

One area of increasing significance is

that of data relating specifically to indi-

viduals.

The rules in Germany, France, Italy,

and Spain, like those in the UK, derive

from the Data Protection Directive

(95/46/EC) (the Directive), although

the Directive is likely to be replaced by

a Regulation (see box “EU data protec-

tion rules: a summary”).

The views of national regulatory au-

thorities on what is, and is not, accept-

able under the Directive frequently

diverge. So, while the underlying prin-

ciples are similar, it should not be as-

sumed that an approach which is ac-

ceptable in the UK will necessarily be

acceptable to national regulatory au-

thorities in other EU member states.

The Directive applies wherever in-

formation being disclosed contains

personal data. Common examples

include information on employees or

customers made available as part of

due diligence or delivered on comple-

tion.

One approach that can be relevant to

disclosures of personal data is where the

processing is both:

• Necessary for the legitimate inter-

ests pursued by the discloser or the

person receiving the information

(the recipient).

• Not unwarranted by reason of

prejudice to rights, freedoms or le-

gitimate interests of data subjects.

This can, for example, be used to jus-

tify providing information in circum-

stances where the recipient agrees to

use the information only to assess the

value of a business and to keep the in-

formation strictly confidential.

However, this requires care; for exam-

ple, this approach was only recognised

in Spain recently, and the extent of its

application there remains uncertain.

In the US, while federal and state stat-

utes and common law provide some

protections for personal information,

typically the range of information pro-

tected is more limited than in the EU.

The focus of the US rules is on informa-

tion regarding individuals’ health or fi-

EU data protection rules: a summary

All EU member states and members of the EEA must comply with the minimum

standards set out in the Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC). The Directive’s key

provisions include the following:

• The rules apply to “personal data”, in other words, information which relates to

an identifiable individual (a “data subject”).

• Duties are imposed on a “data controller” (a person who determines the purposes

for which, and the manner in which, any personal data are, or are to be, proc-

essed).

• Generally, use and disclosure of personal data must fall within a purpose noti-

fied to the individual, and must satisfy a specified basis of legitimacy.

• Much tighter rules, preventing disclosure without very clear consent in all but

the most exceptional circumstances, cover “sensitive personal data” (including

information on ethnic origin, political opinions, religious beliefs, trade union

membership, physical or mental health, sexual life and commission of any of-

fence).

• A data controller who wishes to disclose data outside the EEA must ensure that

the data will receive adequate protection.

The European Commission (the Commission) recognises some countries as provid-

ing adequate protection. For the US, this requires companies to be registered

under the “safe harbor” scheme. Another solution is the execution of a set of

standard contract clauses approved by the Commission. The approach to this

varies between jurisdictions; authorisation from a national regulatory authority is

sometimes required.

Within groups, binding corporate rules are increasingly used for transfers of per-

sonal data outside the EEA.

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200

PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

27

Feature

nances, children under 13 and students,

and information regarding which prom-

ises or representations have been made.

Given this significantly lower general

level of protection, it is much less likely to

be necessary to make specific provision

for personal data in an NDA with respect

to the US than the EU. In many cases, a

general requirement not to use or disclose

information in ways that are inconsistent

with applicable law will suffice.

NO AGREEMENT

Obligations may arise due to the nature

of the information itself, or the circum-

stances of disclosure, rather than by vir-

tue of an express agreement between the

parties.

For example, in the UK, an equitable

duty of confidence may arise indepen-

dently of contract. If the information

has the necessary quality of confidence

and has been imparted in confidence,

then unauthorised use of that informa-

tion may be actionable, whether or not

there is a contract between the parties.

Furthermore, a “trade secret” may be pro-

tectable whether or not there is an agree-

ment between the parties (see box “Trade

secrets: key practical considerations”).

As a general rule of thumb, confidential

business information that has value and

is not readily ascertainable by other per-

sons in the same industry or business is

capable of being a trade secret.

Trade secrets can range from customer

and supplier lists, to research and devel-

opment and other technical informa-

tion, information about methods of do-

ing business, costing and price details,

and source code for computer software.

However, whether or not a particular

piece of information is a “trade secret”

would have to be considered on a case-

by-case (and country-by-country) basis.

CONTEXT OF DISCLOSURE

The way in which parties deal with one

another may give rise to duties which,

either directly or indirectly, are relevant

to the way confidential information is

dealt with.

In the UK, even absent a clear agree-

ment, the manner of dealings can con-

tribute significantly to creating an

equitable duty of confidence (see “No

agreement” above). This model does

not apply in a similar way in the other

jurisdictions so, in that regard, the UK

is more favourable to a discloser than

other jurisdictions.

However, in relation to implied du-

ties to act in good faith, the UK is sig-

nificantly out of step and disclosers will

generally be better off in the other ju-

risdictions, particularly in continental

Europe (see box “Where duties of good

faith arise”).

The civil codes in Germany, France,

Italy and Spain create a legal duty to ne-

gotiate and act towards the other party

in good faith (see box “Good faith and

confidentiality in European civil law”).

It is not generally possible to contract

out of this duty.

Key elements of the duty of good faith in

these jurisdictions include responsibili-

ties:

• To apply reasonable diligence in

the performance of pre-contractual

and contractual obligations.

• To observe moral and ethical stand-

ards of behaviour where they are

not already implied by local law.

• To inform the other party of rel-

evant important points that the

other party could not discover on

its own, where it is reasonable to

expect to receive such information.

• Not to break off negotiations with-

out reasonable cause in circum-

stances where the other party may

reasonably expect that a binding

agreement will be signed.

When dealing with a country in which

the duty of good faith applies, it is im-

portant to note that the courts may,

in line with the Rome I (593/2008/EC)

and the Rome II (864/2007/EC) Regula-

tions on the law applicable to non-con-

tractual obligations, apply the duty as a

“mandatory rule”.

This means that, even if parties gener-

ally contract on the basis of another gov-

erning law (for example, English law),

the duty may apply.

The remedy for a breach of the duty of

good faith is limited to damages that

would put the other party in the position

it would have been in if the negotiations

had not taken place. Injunctive remedies

are unlikely.

However, it is possible, in cases where the

negotiations are advanced, for damages

to extend to loss of profits caused by the

breach (that is, loss of opportunity).

In California, Delaware and New York,

the differences that a UK lawyer needs to

be aware of are less stark than in conti-

nental European jurisdictions.

Trade secrets: key practical considerations

Once confi dential information is in the public domain, it can no longer be the

subject of confi dence. Trade secrecy will not help to protect something which was

once a secret but has become publicly available, although damages may be recov-

erable for the past misuse.

In some cases, a springboard (time limited) injunction (to compensate for the

defendant’s illegal head start) may be granted, although the law in this area is still

not settled.

Although in some jurisdictions, and in some circumstances, protection may be

implied by law, it is much safer for the person disclosing the information to secure

explicit agreement from the person receiving it to maintain confi dentiality.

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200

28

Feature

PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

In each of these US states, implied duties

of good faith and fair dealing arise only

once parties have entered into a con-

tract. In practice, a duty implied at that

stage is unlikely in most cases to do more

than reinforce express obligations of

confidentiality included in the contract.

Equally importantly, there is no general

duty in these states to continue negotia-

tions. So, unlike in continental Europe,

in Delaware and New York in particu-

lar, entering into an NDA will not ex-

pose parties to liability if they decide to

break off negotiations, even without

cause.

The material exception to this general

rule is California, where “agreeing to

negotiate” (for example, in connection

with a letter of intent or NDA) may limit

a party from terminating negotiations

unilaterally.

CONTRACTUAL PROVISIONS

When drafting an NDA, there are some

specific issues to bear in mind (see box

“Non-disclosure agreement checklist”).

Defining confidential information

In principle, the approach is similar

across all the jurisdictions, although

there are some nuances.

A definition will usually identify a cat-

egory of information (for example, “all

information provided by the discloser to

the recipient” or “all information in the

data room”) and protect those elements

of that information which are “confi-

dential”.

If in any doubt, from the perspective

of the discloser, it is generally better to

draft the basic category relatively widely

(for example, “information in the data

room” may not catch additional in-

formation provided at a management

presentation). However, it is important

to ensure that the scope is limited to in-

formation which is not in the public do-

main.

Generally, in all the jurisdictions dealt

with in this article, information in the

public domain cannot be protected (al-

though collections of pieces of publicly

available information may be protect-

able as the law protects the effort in-

volved in producing the collection). It

might be argued that the law will do the

job for you so the point does not need to

be explicitly covered in the NDA.

However, an explicit carve-out for in-

formation in the public domain is gen-

erally accepted practice across all of

our surveyed jurisdictions (see also box

“Information which ceases to be confi-

dential”).

In many cases, NDAs specify other ex-

ceptions to the definition of confidential

information, such as information that

the recipient has, or knows of, before re-

ceiving the confidential information.

In some circumstances, there may be

specific benefits for the parties in being

clear on where they see the borderline

between confidential and public infor-

mation. Examples of information that

an adviser may wish explicitly to include

to minimise uncertainty are:

• The existence of negotiations or an

agreement.

• A compilation of pieces of public in-

formation compiled in an innovative

way of which no one is aware; this

may represent hundreds of hours of

painstaking work, conferring genu-

ine competitive advantage.

Finally, there may be a risk in some

cases that a failure to limit a restriction

to protectable confidential information

may bring into question a party’s basic

restrictions.

When dealing with any of these jurisdic-

tions, we would therefore recommend

an explicit provision dealing with public

domain information. In doing this, it is

worth bearing in mind that courts across

these jurisdictions will generally inter-

pret definitions of confidential informa-

tion narrowly.

Restrictions

Although the central purpose of an

NDA is to limit disclosure of informa-

tion, it is also important for the discloser

to consider restrictions on the recipi-

ent’s use of that information.

For example, when disclosing informa-

tion to someone it is thinking of doing

business with, the discloser will want the

recipient only to use the information to

explore that joint opportunity and not,

for example, to develop its own business.

In the jurisdictions covered in this ar-

ticle, it is generally possible to restrict

use of confidential information by the

recipient as well as disclosure.

However, the importance to both par-

ties of drafting this language carefully

has been illustrated by a recent Dela-

ware Chancery Court decision (af-

firmed by the US Supreme Court). The

court found that a recipient’s failure to

define clearly how it could use confi-

dential information prevented it from

pursuing a hostile takeover bid of the

discloser while the NDA was in effect

(Martin Marietta Materials, Inc. v Vul-

can Materials Co., No. 254, 2012 (Del.

July 10, 2012)).

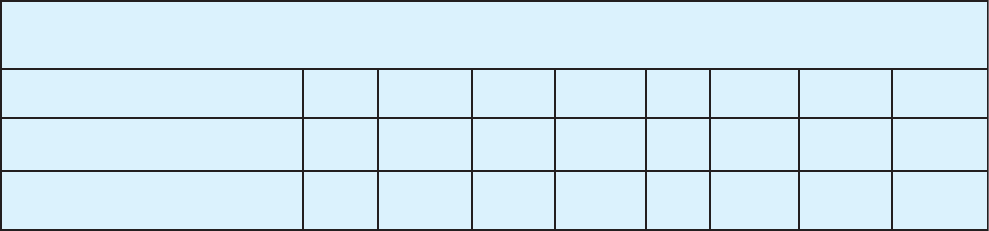

Where duties of good faith arise

France Germany Italy Spain UK California Delaware New York

Pre-contractual duties of good faith

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ x ✓/x x x

Good faith implied in contracts ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ x ✓ ✓ ✓

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200

PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

29

Feature

By their nature, widely-drafted restric-

tions on use can quite easily evolve into

more general restrictions. Breaches of

competition and antitrust laws carry po-

tentially significant penalties across all

of the jurisdictions.

It is therefore universally important to

avoid allowing a restriction on using

confidential information in a competi-

tive activity to be drafted as a blanket

restriction on competing with the dis-

closer.

Additional protections

Where external constraints apply to the

information, an NDA may need to go

further than prohibiting disclosure and

limiting use (see “External constraints”

above).

Three typical examples of this are:

Data protection. In the majority of cases

where information is being disclosed, it

is possible that some element of personal

data will be included (see “Personal

data” above). For example, even the

most basic pack of information regard-

ing a business is likely to include names

and some details of senior management.

If it is possible that information being

made available under an NDA may in-

clude a significant amount of personal

data (for example, access to lists of em-

ployees or individual customers), per-

sonal data issues should be considered at

the outset.

One solution is to ensure that only “de-

personalised” information is provided

(that is, that names and addresses are re-

moved so that the individuals cannot be

identified but the employees or custom-

ers can be profiled). However, this ap-

proach may not work in Spain, as there

are questions over whether information

is truly depersonalised if the discloser

can identify the individuals (even if the

recipient cannot).

If information is not depersonalised, the

discloser should ensure that personal

data issues are addressed in the NDA

(see box “Sample personal data provi-

sion (short form)”).

It is particularly important to limit very

clearly the use which a recipient can

make of personal data and those with

whom it can share that data. In addition,

the NDA should require the recipient to

recognise explicitly that personal data

should be treated with appropriate se-

curity.

Given the sensitivity regarding the

transfer of personal data from mem-

bers of the EEA to the US, the risk that

this may occur should be explicitly ad-

dressed.

One solution is to prohibit transfer out-

side the EEA without the approval of the

discloser. However, when processing

in the US is likely, whether because the

recipient’s principal operations are in

the US or it uses data centres in the US to

store its data, more extensive provisions

are likely to be required.

Third party data. Information being dis-

closed is also likely to contain material

in respect of which the discloser owes

duties to a third party. For example, a

pack of information on the prospects of

a business is likely to refer to the status

of its relationships with potential sup-

pliers or customers.

By disclosing this information, the

discloser may risk breaching its own

confidentiality obligations to the third

party.

There are three main ways of addressing

this:

• Withhold the information in ques-

tion to avoid the discloser breach-

ing its obligations.

• Obtain the consent of the third par-

ty. This may be granted on the basis

that the third party requires direct

rights to enforce the NDA itself.

• Require the recipient specifically to

indemnify the discloser or the third

party (see “Remedies” below).

If the discloser wishes to secure direct

rights for a third party to enforce the

NDA (or benefit from an indemnity in

it), it is generally not necessary to state in

the NDA itself that the benefit under the

NDA can be freely assigned to a third

party.

The benefit of a contractual obligation

to keep information confidential can

usually be assigned unless expressly

prohibited in the agreement. Generally,

assignment is expressly prohibited with-

out consent.

In Italy, NDAs do not usually include the

right to assign the benefit of the agree-

ment, but the benefit can be assigned with

the consent of the counterparty. In Ger-

many, assignment of rights is permitted

as long as such assignment does not con-

stitute a breach of confidentiality itself. In

France, any assignment must be notified

by a bailiff to the non-assigning party.

In the UK, the Contracts (Rights of Third

Parties) Act 1999 (1999 Act) gives a third

Good faith and confidentiality in European civil law

Even without a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), if a party receiving information

fails to maintain the confi dentiality of information it might expect to be confi den-

tial, this may breach the duty of good faith.

Where an NDA has been signed, the duty of good faith may provide an additional

remedy if the recipient misuses confi dential information.

The implied obligation to disclose relevant information makes it particularly impor-

tant to be clear what information is to be disclosed and to protect it in an NDA.

Signing an NDA, of itself, is unlikely to trigger a duty not to break off negotiations

without reason but may contribute to such a conclusion.

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200

30

Feature

PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

party the right to enforce a term of an

NDA if such enforcement is consistent

with the intention of the parties. Parties

can choose whether to rely on the 1999

Act or make an express assignment pro-

vision.

Statutory and regulatory constraints.

There may also be further constraints

applied to the information by statutory

or regulatory authorities in the relevant

jurisdiction. These can arise because

of the nature of the information itself,

or because of the manner in which the

information was obtained. Such con-

straints may need to be specifically ad-

dressed in the NDA itself.

An example in the UK is the official se-

crets legislation which will impose re-

strictions on the disclosure and use of of-

ficial information above the provisions

of an NDA.

In France, information classified as a

military secret, information relating to

a criminal investigation or information

disclosed to a professional in their pro-

fessional capacity (such as a doctor or

lawyer) cannot be disclosed, regardless

of the existence of an NDA. Similar laws

apply in Italy to protect state and official

secrets and such duties of secrecy are not

usually addressed in NDAs and agree-

ments in general.

Exceptions

There are circumstances where a recipi-

ent will feel it needs to have the right to

disclose the confidential information

notwithstanding the NDA. Typical

examples are where the recipient is re-

quired by legislation, regulation or a

court order to disclose the information.

In some of the jurisdictions, it is not es-

sential expressly to provide for all of

these circumstances as the general law

will permit disclosure. For example, in

Italy, a prohibition on disclosure will

be ineffective in the face of a court order

requiring disclosure, even if there is no

provision to that effect in the NDA.

As a result, documents generated in

some jurisdictions may not cover all the

points that parties might expect.

It is therefore sensible to make explicit

provision for all permitted disclosures

in every NDA even if covered by a legal

system where this may be implied. This

ensures clarity and minimises unfore-

seen risks when, for example, the docu-

ment is used in a different context.

Related agreements

It is common for an NDA to form part

of a broader pre-contractual agreement.

Much of this is likely to be expressed as

non-binding heads of terms.

However, alongside the non-disclosure

obligations, the two most common ele-

ments of such agreements which the par-

ties are likely to wish to be able to rely

on are commitments to negotiate exclu-

sively and to allocate the costs of pre-

contractual tasks.

In Italy, France and the UK, a commit-

ment to negotiate will not generally be

enforceable, whereas an undertaking

not to negotiate with anyone else (that

is, effectively granting exclusivity)

will normally be binding. A commit-

ment as to costs should be enforceable

provided that it is sufficiently clear so

that the costs involved and the trigger

for any payment can be objectively

identified.

Similarly, in the US, parties may enter

into exclusivity agreements preventing

the parties from negotiating with other

parties for a specified period of time.

Duration

From a discloser’s perspective, there

is little justification for placing a time

limit on an NDA. After all, if something

remains confidential, there is no reason

why the simple passage of time should

allow it to be disclosed.

However, a recipient will be nervous

about an open-ended confidentiality un-

dertaking. This is particularly the case

where:

• The undertaking restricts use of the

information. The concern here is

that an open-ended provision ex-

poses the recipient to the risk that it

is permanently responsible for any

allegation that a member of its deal

team has used something it learnt

from the information in the course

of another context.

• The information will be stored on

the recipient’s IT systems, as will

inevitably be the case. Particularly

given the extent and complexity of

back-up systems, the recipient will

Non-disclosure agreement checklist

These are the key points to include in a non-disclosure agreement (NDA):

✓ Defi nition of confi dential information.

✓ Core restrictions on disclosure and/or use.

✓ Additional protections for particular information.

✓ Exceptions when the restrictions will be disapplied.

✓ Related agreements (for example, heads of terms).

✓ Duration of the restrictions.

✓ Remedies, such as injunctive relief or fi nancial compensation.

✓ Formalities to ensure that the NDA is effective.

✓ Governing law and jurisdiction.

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200

PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

31

Feature

be exposed to the risk of maintain-

ing security and integrity of data on

those systems indefinitely.

In the UK and Germany, generally there

are no overriding legal limitations on

the duration which can be agreed for

confidentiality undertakings.

Similarly, the California and Delaware

courts generally uphold NDAs that last

indefinitely. This is also broadly the case

in New York, although the New York

courts may apply an assessment of rea-

sonableness to such an issue.

In France, Italy and Spain, unless the

duration of an NDA is specified, there

is a risk that either party will be able to

terminate it at any time. A provision that

the obligations will only endure until

the discloser no longer has an interest

in keeping the information confidential

may obviate this risk, but equally it may

create additional uncertainty.

Overall, therefore, a sensible approach

which is likely to work across these ju-

risdictions is to:

• Provide for a fixed duration for an

NDA.

• Set that period to provide reason-

able and sensible protection for the

discloser while not overburdening

the recipient. In many cases, this

will be between two and five years,

but will depend on the nature of the

information, the industry sector,

and how long the information cov-

ered by the NDA will be considered

relevant.

• Provide protections for the disclos-

er to ensure that the information

will be returned or destroyed before

the end of the NDA.

Remedies

A discloser’s preferred remedy will gen-

erally be injunctive relief: a court order

requiring the recipient to honour the

terms of an NDA.

Financial redress, such as damages, in-

demnities, or possibly “penalties”, are

often second best when compared with

invoking the assistance of the courts

to ensure that confidentiality is main-

tained.

Injunctive relief. In all the jurisdictions,

injunctive relief is potentially available

as a remedy for breach of contract. The

contract does not need to provide ex-

pressly for an injunction. While the de-

tails vary, the courts across the jurisdic-

tions look at similar factors in deciding

whether to grant an interim injunction:

• Whether there is a real risk of im-

minent harm which cannot be ad-

equately compensated financially.

• The likelihood that the discloser

will suffer substantial damage if no

court restraint is placed on the re-

cipient pending a full trial.

• The potential impact on the recipi-

ent of granting an injunction before

a full court trial, and whether there

should be some form of security

from the discloser should the dis-

closer eventually fail to prove its

case.

Within these general principles, there

are some important differences in em-

phasis.

In France, courts may issue an injunc-

tion preserving (or requiring a return

to) the status quo to stop any “mani-

festly unlawful act” or to stop imminent

harm. Such proceedings can be initi-

ated quickly and are extremely effective

where the breach of confidentiality is

manifest.

The practical barriers to obtaining ef-

fective injunctive relief in Spain are dif-

ficult. A common requirement is for the

party requesting an injunction to post a

bond or other financial guarantee. Even

when that is done, there is no guarantee

of the court granting an injunction.

Spanish court proceedings often take

longer than is desirable (and it is neces-

sary to prove the “urgency of the mat-

ter” in order to be granted an injunc-

tion before proceedings begin), given

the practical urgency of cases where a

breach rapidly erodes any sense of con-

fidentiality in the information.

In the US and the UK, the courts will

consider the “balance of hardships”

(“balance of convenience” in the UK)

by analysing the merits of the claim

and comparing the hardship suffered

by the breaching party if an injunction

is granted, to the hardship to the party

seeking the injunction if it is not granted.

(See also box “Reversing the burden of

proof”.)

Financial compensation. In all the ju-

risdictions, damages are, in principle,

available for loss suffered as a result of

the breach of an NDA.

Information which ceases to be confidential

It is generally regarded as appropriate to make clear that information which be-

comes public (or reaches the recipient from a non-confi dential source) after it has

been provided under the non-disclosure agreement (NDA), ceases to be covered by

the NDA, so the recipient can do anything it wants with it.

There is an important qualifi cation to this approach in Italy. There, a distinction is

drawn between documents expressly and specifi cally identifi ed in an NDA as be-

ing confi dential and documents which simply fall within a general defi nition of

confi dential information.

Documents in the fi rst category of documents cannot be disclosed even if the in-

formation in them is subsequently made public. By contrast, if the information

contained in documents in the second category becomes public, the restrictions

on disclosing those documents and their content will fall away.

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200

32

Feature

PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

Only in California, Delaware and New

York is there the potential for puni-

tive damages. Even there, it is not the

norm and damages will only rarely be

awarded punitively (for example, where

there is malicious or wanton conduct).

As a result, in general, damages for

breach of confidentiality across these ju-

risdictions will be awarded to compen-

sate the discloser, rather than to punish

a recipient who has breached his obliga-

tion.

In some cases, the courts have shown

sympathy to aggrieved recipients. For

example, French courts have relaxed

elements of the tests of allowable loss in

some cases where there is a breach of an

obligation to refrain from taking an ac-

tion.

However, there is a consistent practical

challenge, irrespective of jurisdiction, in

proving the financial value of the loss suf-

fered. It is often difficult to know where

information may have leaked to, and to

what use it may be put. As a result, harm

done may not be easily quantified or may

not be apparent at the time of a claim.

General damages are therefore rarely an

effective remedy for breach of an NDA.

Given the challenges associated with

“normal” damages, disclosers will often

want to consider enhancing their ability

to pursue financial claims through ei-

ther or both of:

• An indemnity; that is, an explicit

covenant by the recipient to pay

compensation for loss suffered as a

result of a breach of the NDA.

• A fixed compensation clause; that

is, an undertaking by the recipient

to pay a pre-determined amount by

way of compensation for a breach

of the NDA.

From the discloser’s perspective, by ex-

plicitly giving it a right to be paid, an in-

demnity can potentially simplify the job

of recovering loss and enhance the loss

which is practically recoverable.

Given the difficulties outlined above

of recovering damages for breach of

an NDA, this does have the potential to

make a material difference in at least

some cases (principally those where there

are particular heads of potential loss

which can be identified in an indemnity).

A recipient will question why it would

not be appropriate for the discloser sim-

ply to rely on normal rights to recover

loss.

In the UK, an indemnity is frequently

sought by the discloser, although recipi-

ents will often resist them. As mentioned

above, an indemnity can be particularly

appropriate where it can cover specific

items of loss. For example, a discloser

may be especially concerned about a spe-

cific piece of information falling into par-

ticular hands. It is therefore most often,

although not exclusively, in this type of

situation that an indemnity is agreed.

There is no accepted market practice

outcome to this point of negotiation and

while many NDAs do eventually include

indemnities, many others do not.

The position is similar in Spain and the

US. If the discloser is itself subject to

confidentiality obligations to a third

party with regard to some of the infor-

mation being disclosed, it would not

be unusual for the discloser to seek an

indemnity from the recipient in respect

of a claim which that third party might

make if that information is leaked. In

Spain, a penalty clause may also be ex-

pressed as an indemnity (see below).

In France, Italy and Germany, indem-

nities are not commonly included in

NDAs. Fixed compensation clauses

will provide for the discloser to be paid a

pre-determined amount (rather than an

amount calculated by the actual loss suf-

fered if the recipient breaches the NDA).

They are often referred to as a “penalty”

or “liquidated damages” clause.

Again, while there are differences in

the details, there is a common principle

across most of the jurisdictions. In es-

sence, a fixed compensation clause risks

being unenforceable if the level of com-

pensation is excessive.

In the UK, this is expressed as a princi-

ple that, to be enforceable as a statement

of “liquidated damages”, the clause

must be a genuine pre-estimate of likely

damages. If it cannot be justified on this

basis, it will be unenforceable as a “pen-

alty”.

Similarly, in the US, a clause represent-

ing an effort by the parties to agree on a

reasonable amount of estimated dam-

ages will be treated as an enforceable

“liquidated damages” clause, whereas

a clause providing for an unreasonably

high amount or which is viewed as a

“penalty” is likely to prove difficult to

enforce.

For this reason, and because of the dif-

ficulties of estimating damages flowing

from a breach of confidentiality, fixed

compensation clauses are unusual in

these jurisdictions (see box “Prevalence

of indemnities or fixed compensation

clauses”).

Sample personal data provision (short form)

The recipient acknowledges that the information will include personal data (as

defi ned in EU data protection legislation).

The recipient must ensure that appropriate technical and organisational means are

in place to protect the personal data against unauthorised or unlawful processing

and against accidental loss, destruction or damage by the recipient.

The recipient must not transfer any personal data to a country or territory outside

the EEA without the discloser’s prior consent, such consent not to be unreasonably

withheld or delayed.

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200

PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

33

Feature

In France, Italy and Germany, fixed

compensation clauses are more com-

mon and may be referred to as a pen-

alty. However, to be enforceable, the

required compensation amount must be

reasonable. If it is not, it may be reduced

or increased by the court if manifestly

excessive or insufficient or, under Ger-

man law, held to be void for violation of

public policy. If the discloser can prove

loss in excess of the stated amount, the

excess may be recoverable.

In Spain, parties usually provide for a

penalty which serves as punitive dam-

ages (either in lieu of, or in addition to,

the actual loss suffered) to avoid the

burden of proving actual loss. In some

cases, this may be expressed as indem-

nification in lieu of damages. However,

even here, the courts may reduce puni-

tive damages if they consider them to be

disproportionate.

Overall, therefore, the use of fixed com-

pensation clauses is not unknown, par-

ticularly in the continental European

jurisdictions considered in this article.

However, like indemnities, they are far

from accepted practice. While they can

be used to avoid the need to prove loss,

care needs to be taken to avoid seeking

disproportionately to “punish” the re-

cipient.

Formalities

There are no particular formalities

for NDAs of themselves. Of course, if

the confidentiality undertakings are

included in, or form part of, another

agreement which itself requires special

formalities, those formalities will apply.

Generally, even in the UK, there is no

requirement to have any monetary con-

sideration for an NDA. The disclosure

of information (by the discloser) and the

undertaking to keep it confidential (by

the recipient) constitute sufficient mu-

tual promises to create a binding agree-

ment. Notwithstanding this, it is not

unusual for UK NDAs to be executed as

deeds.

As a practical matter, in France, Italy,

Spain and Germany, it is advisable to

have each party initial the bottom right

hand corner of each page as well as sign-

ing at the end of the agreement. In addi-

tion, in France, an original of the agree-

ment should be made for each party

and each original must specify the total

number of originals.

Governing law and jurisdiction

In the context of international negotia-

tions, a fundamental consideration will

be to ensure that the parties understand

the law which will apply to enforce-

ment of an NDA and the location in

which enforcement action will need to

be taken.

In all of the jurisdictions, a governing

law or jurisdiction clause will generally

be upheld provided that it is not con-

trary to public policy. As regards gov-

erning law, the principal qualification

is that, under the Rome Conventions, a

choice of law clause may not automati-

cally override “mandatory” local law

considerations (see “Context of disclo-

sure” above).

In the context of NDAs, the main area

where this may come into play is in re-

lation to duties of good faith. In certain

circumstances a recipient may be able to

persuade a court in France, Germany, It-

aly or Spain that these duties apply, even

if a contract is expressed to be governed

by English law (see “Context of disclo-

sure” above).

Reversing the burden

of proof

It has become increasingly common

in recent years for non-disclosure

agreements (NDAs) to require the

recipient to prove that it has not

breached the restrictions (for exam-

ple, that it has not used the confi den-

tial information in deciding to take a

particular action or that it independ-

ently devised the information).

From the discloser’s perspective,

the thinking is that this avoids the

considerable practical diffi culties in

proving a breach (for example, prov-

ing the source of a leak).

This approach is far from accepted

practice across all our jurisdictions

and a discloser putting it forward

should expect some resistance.

As a matter of law, in Spain, Ger-

many and the UK, it should gener-

ally be possible expressly to reverse

the burden of proof (subject to lim-

ited exceptions). The position is less

clear cut in France.

In France, if the discloser can prove

that the information was disclosed

to the recipient pursuant to an NDA,

the burden will then shift to the re-

cipient to prove that the information

was, in fact, not protected by confi -

dentiality obligations.

In Italy, it will be up to the discloser

to prove any alleged breach of the

pre-contractual “good faith” duty

(as such, a claim should follow the

same rules provided for claims for

tort). By contrast, in the case of a

claim for contractual liability, the

burden of proof lies on the defend-

ant (that is, the recipient) who will

be required to prove any alleged

breach of the contract was for rea-

sons beyond his contract.

In California, Delaware and New

York, although familiar in practice,

the approach has been little tested

in the courts. However, there ap-

pears no reason to doubt its legal

effi cacy.

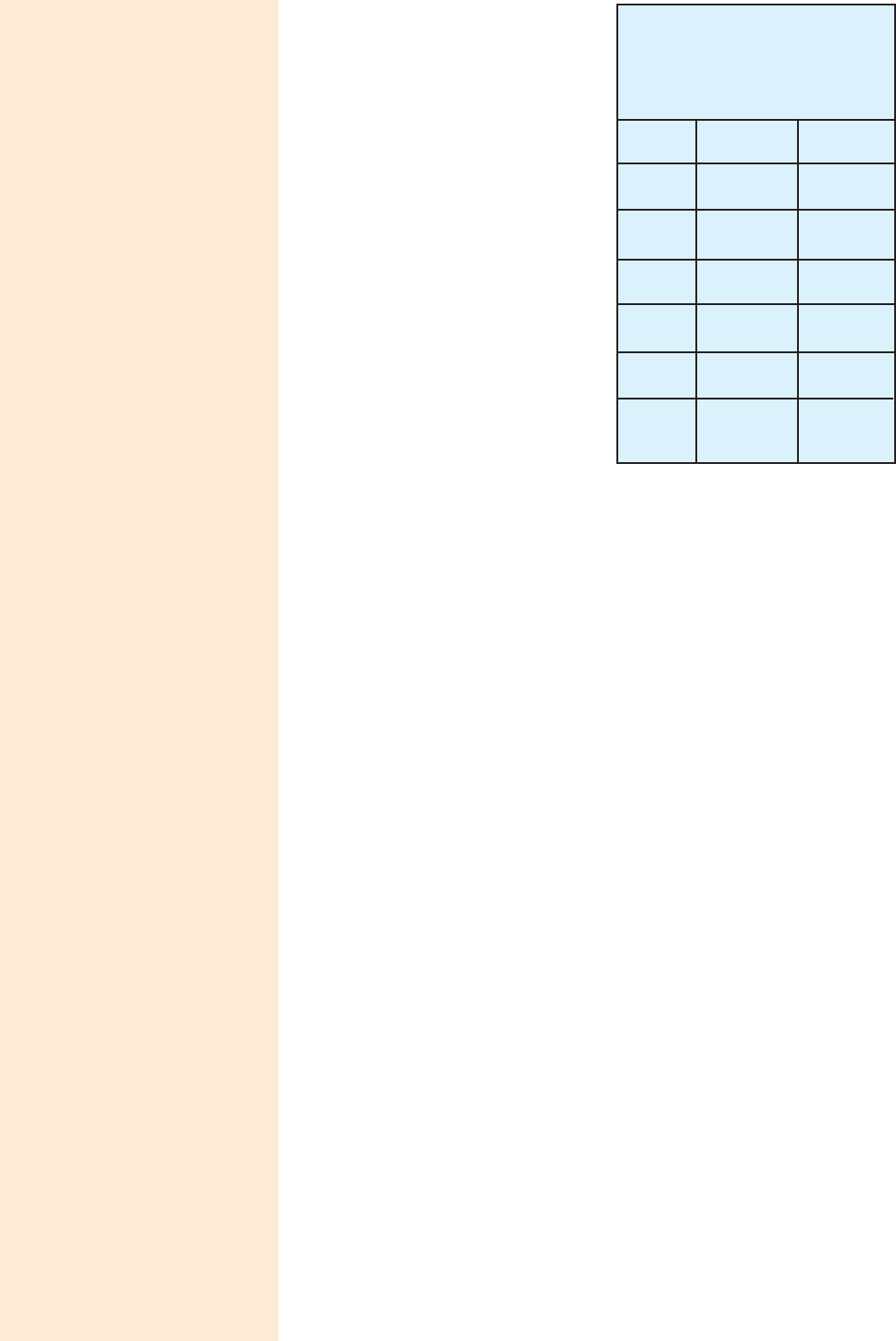

Prevalence of

indemnities or fixed

compensation clauses

Indemnity Fixed loss

France Low Moderate

Germany Low Moderate

Italy Low Moderate

Spain Moderate Moderate

UK Moderate Low

US Low Low

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200

34

Feature

PLC March 2013 www.practicallaw.com

As a general principle, it will be impor-

tant to the discloser to be able to enforce

an NDA quickly, particularly where it

seeks to do so by way of an interim in-

junction.

When providing confidential infor-

mation to a recipient in another juris-

diction, serious consideration should

therefore be given to providing an ex-

plicit ability to enforce the NDA in the

recipient’s local jurisdiction. It is nor-

mally possible to do this in all of the ju-

risdictions which are the subject of this

article.

Particular care should be taken, how-

ever, where the NDA is incorporated

into a broader agreement. In that case,

the parties may, for example, wish to

give the English courts exclusive juris-

diction over other aspects of the agree-

ment, with a specific exception to enable

enforcement of the recipient’s confi-

dentiality undertakings directly in the

courts of the recipient’s jurisdiction.

In certain circumstances, in France,

Spain and Germany, courts retain the

power to grant interim measures even

where the court is not competent in the

matter itself. However, French courts

will only exercise this power in excep-

tional circumstances and where there is

a connection to France.

The practical point with respect to both

governing law and jurisdiction is to con-

sider realistically how close a connec-

tion the negotiations have with a par-

ticular jurisdiction.

The broad principles applying across

the countries analysed are similar.

Provided, therefore, that the scope

of an NDA is limited to protection

of confidential information and the

NDA is drafted in a reasonable man-

ner, a UK-based discloser should not

generally be overly concerned by the

prospect of accepting that the NDA be

governed by the laws of any of those

jurisdictions.

For a UK-based discloser dealing with

a recipient in one of the other jurisdic-

tions, it may be easier to enforce the

confidentiality obligations that it cares

about under the recipient’s own legal

system. This benefit may well outweigh

any nervousness it might have about al-

lowing that legal system to govern the

NDA.

Peter Watts is a partner in the London

office, Philipp Grzimek is a partner in

the Frankfurt office, Marco Berliri is a

partner in the Rome office, Alex Dol-

mans is a partner in the Madrid office,

Winston Maxwell is a partner in the

Paris office, Lorig Kalaydjian is an as-

sociate in the Los Angeles office, and

Ellie Pszonka is a trainee in the London

office, of Hogan Lovells International

LLP.

Related information

Links from www.practicallaw.com

This article is at www.practicallaw.com/1-524-1008

Topics

Asset acquisitions www.practicallaw.com/5-103-1079

Confi dentiality www.practicallaw.com/7-103-1304

Cross-border: acquisitions www.practicallaw.com/9-103-1077

Cross-border: commercial and international trade www.practicallaw.com/8-103-2044

Data protection www.practicallaw.com/8-103-1271

Preliminary agreements www.practicallaw.com/9-103-1138

Share acquisitions: private www.practicallaw.com/1-103-1081

Practice notes

Confi dentiality: acquisitions www.practicallaw.com/0-107-4684

Data protection issues on commercial transactions www.practicallaw.com/5-200-2146

Heads of terms: acquisitions www.practicallaw.com/4-107-4682

Protecting confi dential information: overview www.practicallaw.com/8-384-4456

Previous articles

Data protection: how to seal the deal (2010) www.practicallaw.com/4-503-6370

Data protection: impact on commercial transactions (2003) www.practicallaw.com/9-102-3685

For subscription enquiries to PLC web materials please call +44 207 202 1200

© Practical Law Publishing Limited 2013. Subscriptions +44 (0)20 7202 1200