NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

CULTURES OF CORRUPTION: EVIDENCE

FROM DIPLOMATIC PARKING TICKETS

Raymond Fisman

Edward Miguel

Working Paper 12312

http://www.nber.org/papers/w12312

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

June 2006

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National

Bureau of Economic Research.

©2006 by Raymond Fisman and Edward Miguel. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed

two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is

given to the source.

Cultures of Corruption: Evidence From Diplomatic Parking Tickets

Raymond Fisman and Edward Miguel

NBER Working Paper No. 12312

June 2006

JEL No. K42, Z13, D73, P48

ABSTRACT

Corruption is believed to be a major factor impeding economic development, but the importance of

legal enforcement versus cultural norms in controlling corruption is poorly understood. To

disentangle these two factors, we exploit a natural experiment, the stationing of thousands of

diplomats from around the world in New York City. Diplomatic immunity means there was

essentially zero legal enforcement of diplomatic parking violations, allowing us to examine the role

of cultural norms alone. This generates a revealed preference measure of government officials'

corruption based on real-world behavior taking place in the same setting. We find strong persistence

in corruption norms: diplomats from high corruption countries (based on existing survey-based

indices) have significantly more parking violations, and these differences persist over time. In a

second main result, officials from countries that survey evidence indicates have less favorable

popular views of the United States commit significantly more parking violations, providing

non-laboratory evidence on sentiment in economic decision-making. Taken together, factors other

than legal enforcement appear to be important determinants of corruption.

Raymond Fisman

Uris 823

Columbia University

Graduate School of Business

New York, NY 10027

and NBER

Edward Miguel

Department of Economics

University of California

549 Evans Halls #3880

Berkeley, CA 94720-3880

and NBER

emiguel@econ.berkeley.edu

1. Introduction

The underlying causes of corruption remain poorly understood and widely debated. Yet the study of

corruption beyond the realm of opinion surveys is still in its infancy, and there is little firm evidence

relating corruption to real-world causal factors. Notably, social norms are often mentioned as a primary

contributor to corruption in both the academic literature and the popular press, yet there is no evidence

beyond the most casual of cross-country empirics.

1

Research on the causes of corruption is compounded by the difficulties inherent in disentangling

the effect of social norms versus legal enforcement: societies that collectively place less importance on

rooting out corruption, and thus have weak anti-corruption social norms, may simultaneously have less

legal enforcement. Understanding the relative importance of these potential causes of corruption is of

central importance in reforming public institutions to improve governance: if corruption is predominantly

controlled through anti-corruption social norms, interventions that focus exclusively on boosting legal

enforcement will likely fail.

We develop an empirical approach for evaluating the role of social norms in corruption by

studying parking violations among international diplomats living in New York City. Consular personnel

and their families benefit from diplomatic immunity, a privilege which allowed them to avoid paying

parking fines prior to November 2002. We examine differences in the behavior of government employees

from different countries, all living and working in the same city, all of whom can act with impunity in

(illegally) parking their cars. The act of parking illegally fits well with a standard definition of corruption,

i.e., “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain,”

2

suggesting that the comparison of parking violations

by diplomats from different societies serves as a plausible measure of the extent of corruption social

norms or a corruption “culture”.

1

See Lambsdorff (2005) for an overview of findings on culture and corruption based on cross-country comparisons.

Witzel (2005) provides one of many discussions on the topic in the popular press. Mauro (2004) discusses several

models of multiple equilibria in corruption levels that could be seen as capturing corruption culture. Tirole (1996)

develops a model of bureaucratic collective reputation that also implies persistent corruption.

2

This is the definition used by the international anti-corruption organization Transparency International (see

http://ww1.transparency.org/about_ti/mission.html, accessed online March 9, 2006).

1

This setting has a number of advantages. Most importantly, our approach avoids the problem of

differential legal enforcement levels across countries, and more generally strips out enforcement effects,

since there was essentially no enforcement of parking violations for diplomats during the main study

period. We thus interpret diplomats’ behavior as reflecting their underlying propensity to break rules for

private gain when enforcement is not a consideration. Additionally, because U.N. diplomats are largely

co-located in Midtown Manhattan, we avoid many concerns of unobserved differences in parking

availability across geographic settings.

The first contribution of this approach lies in allowing us to construct a “revealed preference”

measure of corruption for government officials across 146 countries. This objective measure, based on

real rule-breaking in parking, is arguably an improvement over existing country corruption indices that

are typically based on subjective surveys, and it is certainly much cheaper data to collect.

3

Other existing

corruption measures are also difficult to interpret – what does moving from a score of “1” to a score of

“2” on a cross-country index really mean? – while our parking violations measure has a much more

precise definition and explicitly cardinal interpretation.

In our main empirical result, we find that this parking violation corruption measure is strongly

positively correlated with other country corruption measures, and that this relationship is robust to

conditioning on region fixed effects, country income, and a wide range of other controls (including

government employee salary measures). This finding arguably validates the usefulness of the new

measure. It also goes against the predictions of standard economic models of crime in situations of zero

legal enforcement (e.g., Becker 1968). These would predict that parking violations should be high across

the board for all diplomats when enforcement is lifted. Instead we find that diplomats from low corruption

countries (e.g., Norway) behave remarkably well even in situations where they can get away with

violations, while those from high corruption countries (e.g., Nigeria) commit many violations, suggesting

that they bring the social norms or corruption culture of their home country with them to New York City.

3

In this sense, our corruption measure is conceptually similar to the Economist magazine’s “Big Mac Index” as a

measure of country purchasing power parity.

2

An alternative explanation for this pattern warrants mentioning upfront. It is possible there are

stronger social sanctions – for example, public embarrassment through the media upon returning home –

in low corruption countries against diplomats who commit many parking violations while in New York,

relative to diplomats from high corruption countries. If the potential response of others in the home

country, either informally or formally, is responsible for limiting parking violations, then diplomats’

behaviors are better interpreted as an indication of their home country’s cultural tolerance for corruption

rather than their own personal values. However, this is still consistent with our basic interpretation of the

level of New York City parking violations as a revealed preference measure of country corruption norms.

The parking violations data exist at the individual diplomat level for all U.N. mission diplomats

present in New York City (numbering over 1700 at any given point in time), allowing us to study how

individual behavior evolves over time in a situation of zero enforcement. For diplomats from high

corruption countries of origin, a model of convergence to United States corruption norms would

(presumably) predict a decline in the rate of parking violations over time, as tenure in the U.S. increases.

By contrast, a model of convergence to the “zero enforcement” norm discussed above would imply an

increase in violations over time, particularly for officials from low corruption countries. We do find

evidence that the frequency of violations increases with tenure in New York City. However, in contrast to

both models of norm convergence, there is a statistically significant positive interaction effect of home-

country corruption levels and tenure in New York City, implying much greater increases in violations

over time among diplomats from the high corruption countries.

The parking violation dataset also provides a novel window into the related issues of sentiment

and affinity in individual decision-making. It is often claimed that sentiment has a major impact on

important economic decisions as suggested, for example, by the frequent use of consumer boycotts to

pressure corporate policies and the “capitalization of patriotism” in low yield war bonds. However, the

3

empirical evidence on this score remains contested.

4

We find that diplomats from countries where popular

attitudes towards the United States tend to be unfavorable (based on comparable cross-country survey

data) have significantly more parking violations than those from countries where attitudes towards the

United States are largely positive. This setting is one in which diplomats can indulge their personal tastes

for rule-breaking without punishment, and it appears that diplomats from countries where the U.S. is

unpopular derive positive utility from breaking U.S. rules (or suffer less disutility than other diplomats

from doing so).

A final empirical finding is worth highlighting. In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001

attacks, there was a sharp – though temporary – drop in diplomatic parking violations, by roughly 80%.

We find that countries with greater proportions of Muslim population experience particularly sharp

declines. We can only speculate about the exact causes of this change in behavior, but the fear of police

harassment or negative media attention for their home country during that politically delicate period is a

possibility. Also recall that there were hundreds of attacks on Muslims in the United States in the weeks

following the 9/11 attacks (Council on American-Islamic Relations 2002).

The main theoretical implication of these empirical patterns, taken together, is that culture,

norms, and emotions – in other words, factors other than legal enforcement – play a key role in

government officials’ corruption decisions. They suggest that understanding these factors should be taken

seriously in debates about the causes of corruption and the policy measures to combat it.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: section 2 describes the diplomatic parking situation in

New York City and the violations data, section 3 discusses the rest of the dataset, section 4 contains the

empirical results and the final section concludes.

2. Diplomatic Parking Violations in New York City

4

There is a small but growing literature on consumer sentiment and purchasing behavior. Chavis and Leslie (2006)

examine the effect of the Iraq War on French wine sales and find mixed results. In the domain of corporate social

responsibility, Hiscox and Smyth (2006) find that “good labor” labels have a strong impact on consumer demand.

4

Diplomatic immunity provides consular officials and their families with protection from prosecution or

lawsuits in their host country. The original intent of these laws was to protect diplomats from

mistreatment abroad, especially in countries not on friendly terms with the home country.

5

However,

these days diplomatic immunity is more commonly viewed as the “best free parking pass in town” (BBC

1998). Diplomatic vehicles possess license plates tagged with the letter “D” that signals diplomatic

status.

6

While these vehicles may be ticketed, the car’s registrant is shielded from any punishment for

non-payment of the ticket. Thus one immediate implication of diplomatic immunity – not just in New

York, but also in most other capitals (e.g., London (BBC 1998), Paris (Agence Presse-France 2005),

Seoul (Korea Times 1999)) – has been that it allows diplomats to park illegally but never suffer any threat

of legal punishment, leaving a “paper trail” of illegal acts with no consequences.

7

To illustrate the

magnitude of the problem, between November 1997 and the end of 2002 in New York City, diplomats

accumulated over 150,000 unpaid parking tickets, resulting in outstanding fines of more than $18 million.

The parking violations data are at the level of the individual unpaid violation.

8

Drivers have 30

days to pay a ticket before it goes into default, at which point an additional penalty is levied (generally

110% of the initial fine). Diplomats then receive an additional 70 days to pay the ticket plus this penalty

before it is recorded in our dataset as an unpaid violation in default. The information on each violation

includes the license plate number, the name and country of origin of the car’s registrant, the date, time

and location of the violation, the fine and penalty levied, and amount paid (if any). The most common

diplomatic parking violation was parking in a “No Standing – Loading Zone” (43% of violations). The

remainder were spread across a wide range of violation types that imply varying degrees of social harm

9

:

fines for expired meters accounted for 6% of the total, double-parking for 5%, and parking in front of a

5

While the origins of diplomatic protection date back many centuries, the current incarnation is found in the Vienna

Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961. See http://www.un.int/usa/host_dip.htm for the full text.

6

Note that while the vehicle’s diplomatic status is revealed by the license plate, there is nothing that identifies the

country of origin of the vehicle’s registrant.

7

See http://www.state.gov/m/ds/immunities/c9127.htm.

8

We gratefully acknowledge the New York City Department of Finance, in particular Sam Miller and Gerald

Koszner, for compiling these data.

9

Almost all parking violations in the dataset resulted in fines of US$55, making it impossible to assess the extent of

social damage by violations’ relative prices.

5

fire hydrant 7%, for instance. We present analyses for different types of violations below. Also note that

in 20% of violations the registrant is the mission itself, signifying an official rather than personal vehicle.

We return to this below in describing our individual-level results. The period of coverage is November

24, 1997 to November 21, 2005. (Refer to the Data Appendix for a more detailed description of the New

York City parking violations dataset.)

A crucial change in legal enforcement took place in October 2002, with the implementation of the

Clinton-Schumer Amendment (named after the two senators from New York State), proposed by the

Bloomberg administration to deal with the diplomat parking problem. This law gave the City permission

to tow diplomatic vehicles, revoke their official U.N. parking permits, and have 110% of the total amount

due deducted from U.S. government aid to the offending diplomats’ countries of origin (Singleton 2004).

Parking violations fell substantially after this reform, suggesting that increased enforcement can sharply

reduce corruption, but the basic cross-country patterns remain unchanged, as we discuss below.

We thus mainly focus on the pre-reform period, November 1997 through October 2002, since it is

closest to the zero legal enforcement environment we are interested in. For most of the analysis we

employ the total amount of unpaid parking violations for a particular country’s diplomats conditional on

the total number of U.N. permanent mission staff with diplomatic privileges. We obtain staff information

from the U.N. Bluebook for May 1998. Published twice annually, the Bluebook lists all U.N. mission

staff, as well as their official titles. We additionally use U.N. Bluebooks for 1996–2002 to track the U.N.

tenure of individual level violators. Fortunately, the Bluebooks use consistent spellings across editions,

facilitating automated matching across time. In a majority of cases, the spelling and format were also

consistent with the names in the parking violations data; the algorithm automatically matched 71% of

diplomats in the violations database (see the Data Appendix for further details). The first Bluebook we

use is from February 1996, and we use this as our start date for calculating tenure at the United Nations.

That is, we cannot distinguish among arrival times pre-1996, and all individuals included in the February

1996 Bluebook are coded as arriving in that month. As a robustness check, we also limit the sample only

6

to diplomats who were not yet present in New York in the 1996 Blue Book (reducing the sample by

16%), which allows us to more accurately capture arrival dates, as discussed below.

We also obtained data on the number of diplomatic license plates registered to each mission from

the U.S. Department of State’s Office of Foreign Missions, and we use this data as a control variable in

some specifications. Unfortunately, these data are only available for 2006, though we were assured that

these numbers are largely stable over time.

10

Table 1 presents the annual number of violations per diplomat during November 1997 – October

2002 period by country, along with the total number of diplomats from the May 1998 U.N. Bluebook.

Overall, the basic pattern accords reasonably well with common perceptions of corruption across

countries. The worst parking violators – the ten worst are Kuwait, Egypt, Chad, Sudan, Bulgaria,

Mozambique, Albania, Angola, Senegal, and Pakistan – all rank poorly in cross-country corruption

rankings. While many of the countries with zero violations accord well with intuition (e.g., the

Scandinavian countries, Canada), there are a number of surprises. Some of these are countries with very

small missions (e.g., Burkina Faso and the Central African Republic), and a few others have high rates of

parking violations but do pay the fines (these are Bahrain, Malaysia, Oman, and Turkey; we return to this

issue below). The smallest missions may plausibly have fewer violations since each mission is given two

legal parking spaces at the United Nations and this may suffice if the country has very few diplomats.

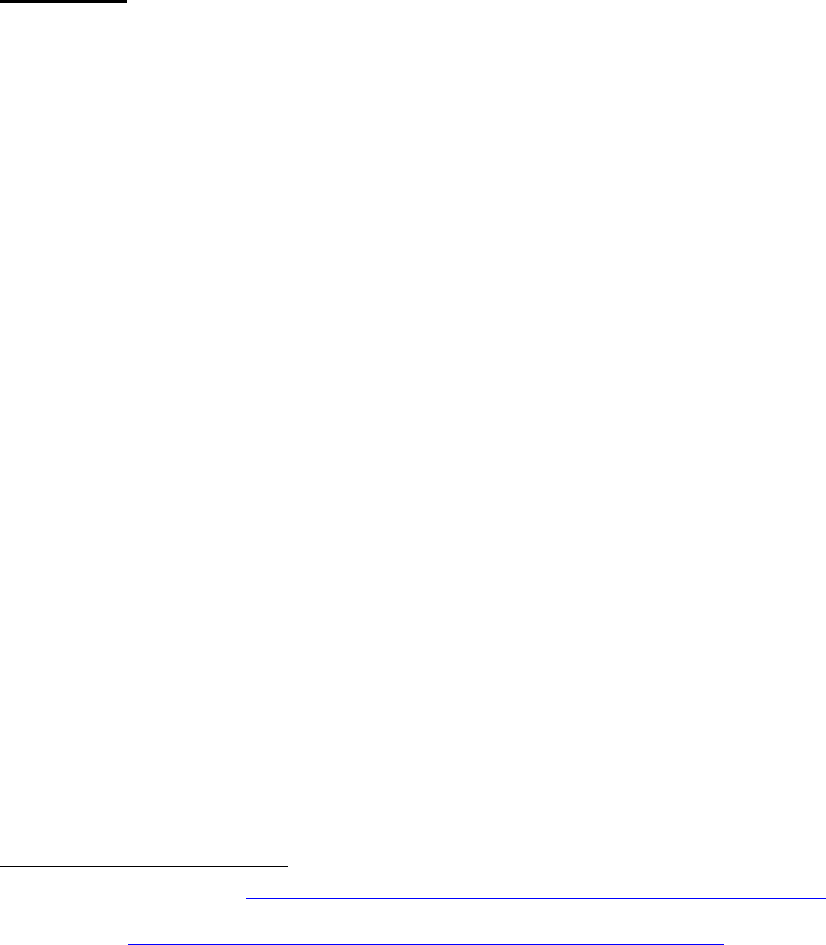

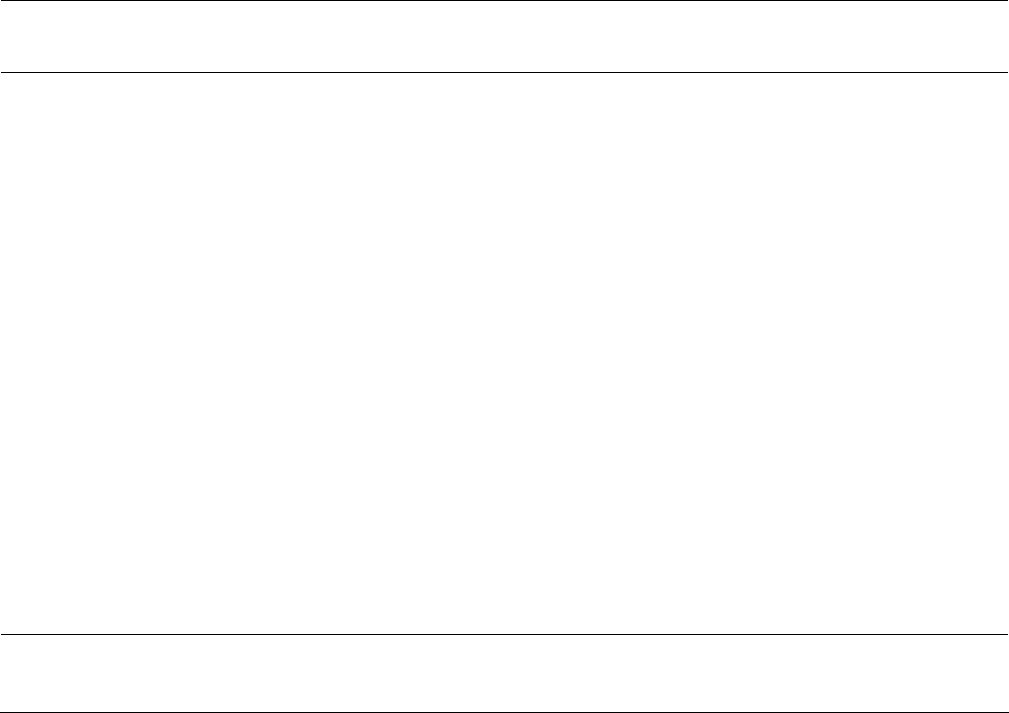

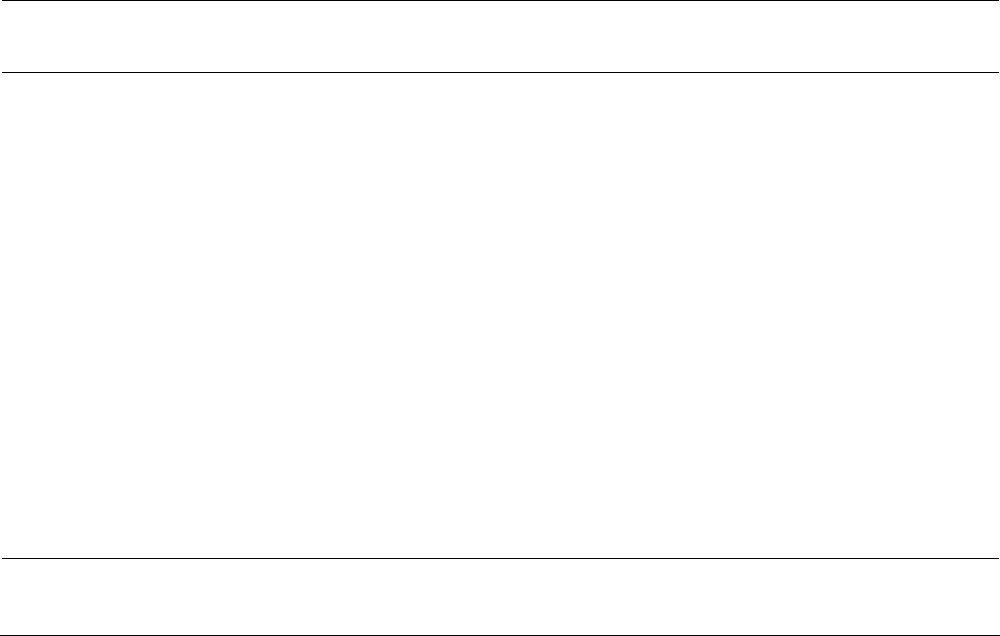

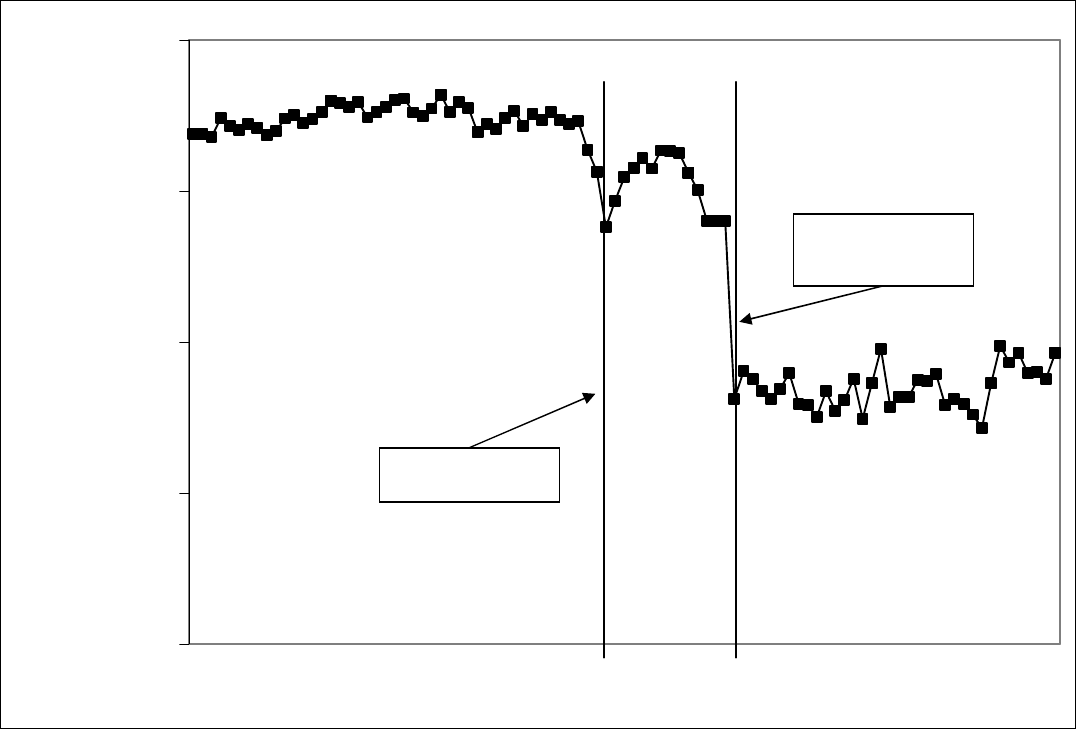

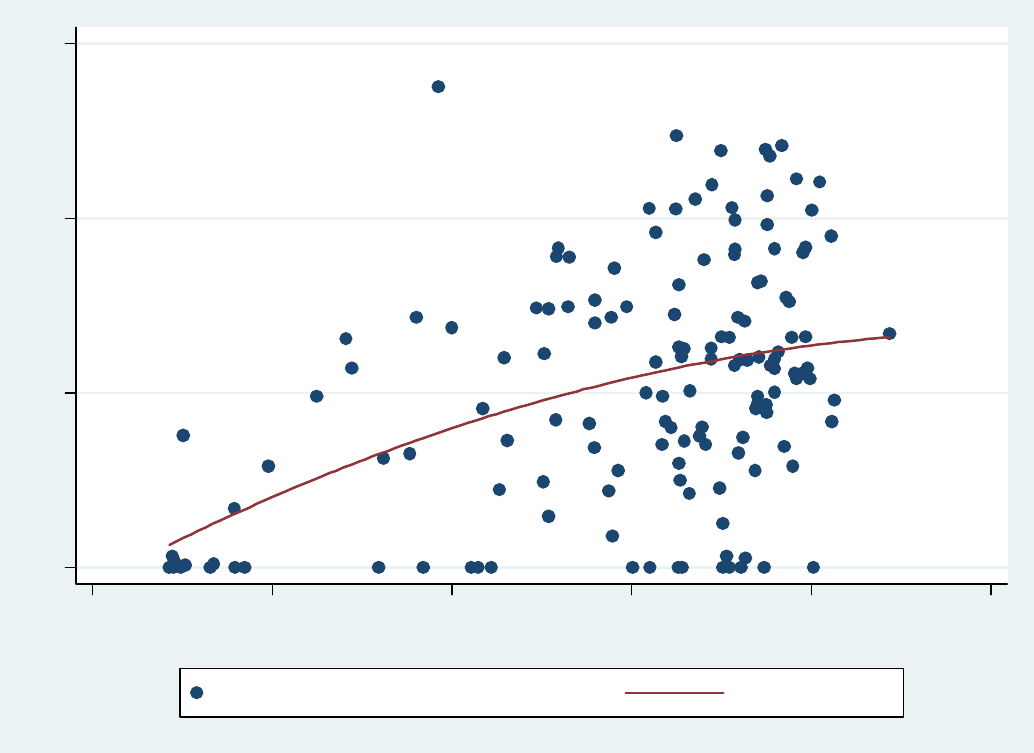

Figure 1 plots the total violations per month during November 1997 – November 2005. There are

two clear declines in the number of violations – the first comes in September 2001, corresponding to the

period following the World Trade Center attack. The second and more pronounced decline coincides with

increased enforcement in New York City.

3. Cross-country data

We also employ country-level data on economic, political, and social characteristics, and in particular

consider data on country corruption levels, using the corruption measure in Kaufmann et al (2005) from

10

We thank Murray Smith of the U.S. Office of Foreign Services for these data and for many useful conversations.

7

1998, the earliest year with wide country coverage. This is a composite corruption index that is essentially

the first principal component of a number of other commonly used corruption indices. By definition,

therefore, it is quite highly correlated with the commonly used indices and is extremely highly correlated

(=0.97) with the Transparency International (TI) ratings from the same year. For ease of interpretation,

we reverse the sign of the original measure so that higher values indicate greater corruption. The mean

value of this measure is zero, and it ranges from -2.6 to +1.6 in our sample of countries. The main

advantages of this country measure are that its method of aggregation is clearly defined relative to the TI

measure, and it has broader country coverage than other indices.

The Pew Global Attitudes Survey

11

from 2002 (the earliest year that the survey was performed)

provides a measure of anti-American sentiment based on responses to the question: “Please tell me if you

have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable or very unfavorable opinion of the

United States.” This is coded to take on values from one (most favorable) to four (least favorable) and

then averaged across respondents. To control for general aversion to foreigners, we similarly code

responses to another question from the Pew survey that asks respondents their attitudes towards a

dominant regional country (for example, Argentines are asked to give their opinion of Brazil). The five

countries in the Pew dataset whose citizens viewed the U.S. most favorably in 2002 are Honduras,

Venezuela, Ghana, Philippines, and Nigeria, while the five that viewed the U.S. least favorably are Egypt,

Pakistan, Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon. The preponderance of Middle Eastern countries may in part be

due to popular opposition there to the U.S. invasion of Iraq, which was imminent by late 2002.

Unfortunately, the Pew data are not available prior to 2002 and thus we are unable to explore whether

changes in popular attitudes over time affect New York City parking violations.

We include a number of other variables that may affect incentives to comply with local laws.

From the data of Kuziemko and Werker (2006), we generate an indicator variable denoting whether the

country received foreign aid from the United States in 1998. We similarly generate a pair of indicator

variables for military and economic aid, respectively, since these two types of aid may reflect different

11

These data are publicly available online at http://pewglobal.org/ (accessed March 9, 2006).

8

geopolitical interests: while economic aid recipients may feel beholden to the United States, those

receiving military aid are typically countries that the United States requires as strategic allies.

Finally, we consider whether unpaid violations appear to be driven by an income effect. We

include the logarithm of GDP per capita in 1998 in U.S. dollars taken from the World Development

Indicators in most specifications. Country-level income per capita is strongly correlated with corruption

and with the rule of law, and may be caused in part by underlying corruption levels, complicating efforts

to disentangle corruption effects from income effects. As we discuss below, despite this strong correlation

the main corruption results are robust to including a linear income control. Second, we include the ratio of

government bureaucrats’ salaries to GDP per capita (using data from Schiavo-Campo et al 1999) for the

early 1990s (exact year differs by country) to account for the possibility bureaucrats occupy different

positions in the national income distribution.

Our sample consists of all countries that had 1998 populations greater than 500,000 according to

the World Development Indicators, and for which basic country-level data were available. Table 2

presents summary statistics for both the country-level and diplomat-level variables.

4. Empirical Results

The main econometric specification in the cross-country analysis is presented in equation 1:

log(1+Average annual unpaid parking violations)

i

= α + β

1

log(Diplomats)

i

+ β

2

Corruption

i

+ X

i

′γ + ε

i

(1)

where i denotes the country, Corruption is the 1998 country corruption index, and X is a vector of other

country controls, including region fixed effects, the log of GDP per capita in 1998, among others

depending on the specification, and

ε

is a standard white noise disturbance term.

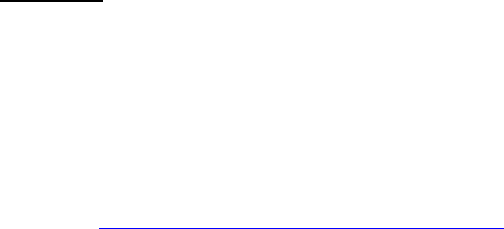

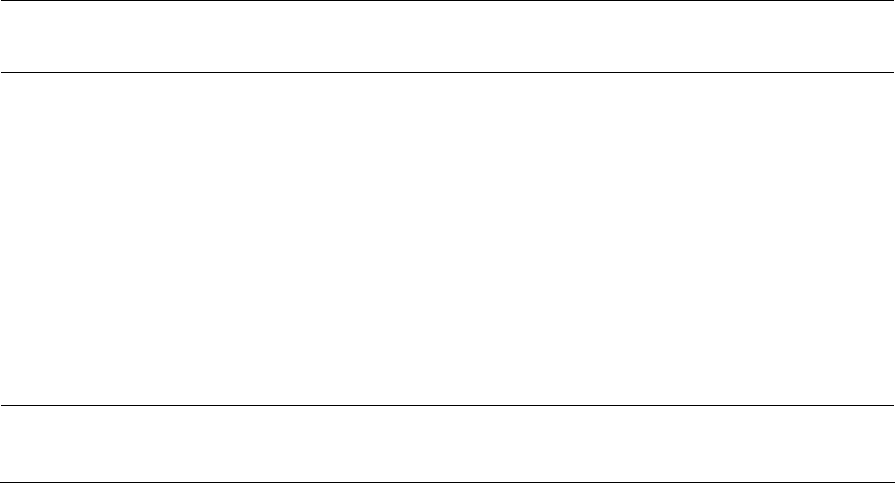

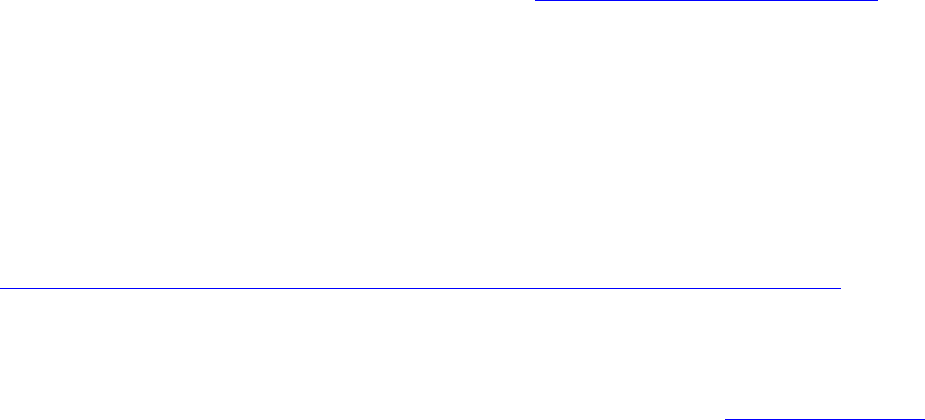

The New York City unpaid parking violations measure is robustly positively correlated with the

existing country corruption index conditional on the number of U.N. mission diplomats for that country in

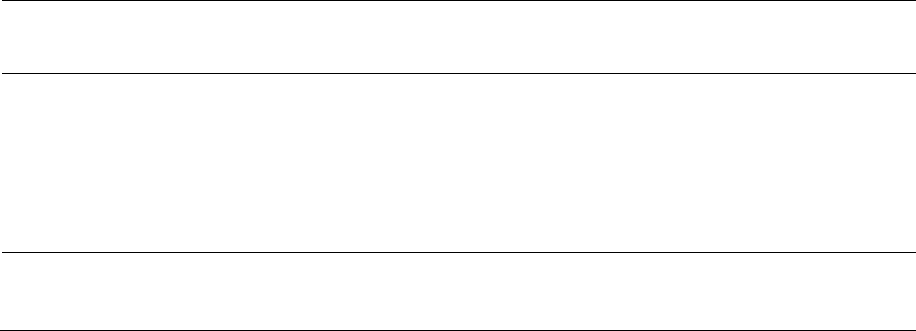

New York City (Table 3, regression 1). The relationship is roughly linear (Figure 2). The coefficient

9

estimate on the country corruption index is robust to the inclusion of log per capita income (regression 2)

and also to the log of the number of vehicles registered to each mission as a control (regression 3),

12

though the point estimate drops by nearly half using the income control. The result is also robust to

controlling for the average government wage relative to per capita income (regression 4) and to region

fixed effects (regression 5). The regions with the greatest average number of unpaid parking violations

relative to the reference region (North America and the Caribbean) are Africa and the Middle East. Note

that while the coefficient on corruption is robustly significantly significant across these specifications, the

coefficient on country per capita income is sensitive to the choice of sample and covariates.

The strong relationship between the parking violation corruption measure and the country

corruption index also holds if the dependent variable is log(1 + Average annual unpaid parking violations

/ Diplomats) across specifications (Table 4), is robust to specifications where log(Diplomats) is included

as an additional control (results not shown), and similarly holds if a tobit specification is used rather than

OLS (Appendix Table A1).

We obtained similar data on parking violations by embassy diplomats in London as a further

robustness check. This information is reported annually in the minutes of the U.K. House of Lords, as is

information on the number of diplomats from each country residing in London. We use data for the years

1998-2002 to best match the New York City analysis. The London data is coarser than the New York City

data in several ways. First,, only country violation totals are reported (rather than the detailed micro-data

available for New York City), and countries with fewer than ten violations are not reported. Further, the

fact that foreign embassies are scattered throughout London further complicates the interpretation relative

to New York City where U.N. missions are co-located in Midtown Manhattan and thus diplomats face a

similar parking environment. Despite these differences, the results imply a relationship between country

corruption and diplomatic parking violations in London that is remarkably similar to the estimated effects

for U.N. diplomats in New York. In regressions analogous to Table 3 but using London parking violations

12

A specification using fixed effects for the number of vehicles per mission generates similar results (results not

shown). Further, these estimated fixed effects are uniformly increasing in the number of vehicles, implying a

monotonic relationship consistent with the linear functional form we report in the table.

10

as the dependent variable, the coefficient estimate on the country corruption index takes on values ranging

between 0.38 and 0.70, and these effects are statistically significant at over 90% confidence across all

OLS and tobit specifications (results not shown).

The coefficient estimate on the country corruption measure in the New York City data remains

positive and large (0.3) but loses statistical significance if quadratic and cubic polynomials for the log of

country per capita income are included controls, in part because standard errors increase (regression not

shown). However, the implied relationship between country per capita income and parking violations is

non-monotonic: it rises up through (roughly) average per capita income in the sample, before declining.

This pattern argues strongly against the explanation that richer countries are simply able to purchase more

parking spots for their diplomats, in which case we would expect a monotonic negative relationship

between country income and parking violations. We prefer to focus on the specification with a linear log

per capita income control since doing so most directly addresses theoretically well-motivated concerns

about such monotonic income effects, rather than including additional highly collinear income controls.

13

Since we can follow individual diplomats during their tenure at the U.N., we examine the related

question of whether there is any evolution of diplomat behavior while in New York City. Conceptually,

the relative plausibility of socialization to U.S. norms versus convergence to a uniform high corruption

norm is unclear. If convergence is to U.S. corruption norms, individuals from high corruption countries

should have declining parking violations over time, but there be should be no change in behavior for

diplomats from the low corruption societies. Alternatively, individuals may begin their stay in NYC

unsure as to the extent they can get away with parking violations. Once they successfully “get away with

it” a few times (or hear stories about others getting away with it) and learn about the reality of zero

enforcement, diplomats may become bolder in their violations. Thus convergence to this “zero

enforcement” norm predicts increasing parking violations over time, particularly among diplomats from

low corruption countries. In practice to estimate these effects we use a regression equation of the form:

13

The strong empirical relationship between country corruption and income may theoretically reflect causal impacts

in both directions (poorer countries become more corrupt, or corrupt countries become poorer), and this complicates

the interpretation of regressions where both terms are included as controls.

11

log (1 + Monthly unpaid parking violations)

ijt

= α

t

+ β

1

log(Months in NYC)

ijt

+ β

2

{log(Months in NYC)

ijt

*Corruption

i

} + X

ijt

′γ + ε

ijt

(2)

where i again denotes a country and j denotes an individual diplomat from that country in month t, X

ijt

is a

vector of individual diplomat characteristics, and the final term is the error, which is allowed to be

correlated across monthly observations for the same individual. We include month fixed effects (α

t

) in all

specifications, and also sometimes include diplomat fixed effects (α

ij

). The two key terms in this analysis

are β

1

, the effect of increased time spent working as a consular official in New York City on parking

violations for diplomats from countries with a corruption index of zero (corresponding to average

corruption in the sample), and β

2

, the differential time effect for diplomats from countries with higher

corruption.

The frequency of unpaid violations increases rapidly and statistically significantly with tenure in

New York City (Table 5, regression 1). On average parking violations increase by 8-18% with a doubling

of the length of tenure in New York City. This result is robust to the inclusion of diplomat fixed effects

(regression 2), and to the use of a discrete measure of violations (regressions 4 and 5). In contrast to

models of convergence to U.S. corruption norms, we do not find a negative interaction effect of home-

country corruption levels and tenure in New York. Rather the coefficient estimate on this interaction term

is positive and statistically significant, implying that there is a divergence in the rate of violations over

time, with diplomats from high corruption countries showing increasingly more violations relative to

diplomats from low corruption countries over time, perhaps as they learn about the reality of diplomatic

immunity. However, the point estimates indicate that even diplomats from very low corruption countries

(those with corruption index scores below -2, say) show some smaller increases in violations over time.

Finally, we note that the results are virtually identical if we repeat the analysis dropping individuals that

arrived only after the earliest U.N. Bluebook was published (results not shown), which allows us to more

accurately capture date of arrival but reduces the sample. An additional robustness check based on a split

of the sample by country average parking violations also generated similar results (results not shown).

12

Various measures of proximity to the U.S. are correlated with fewer unpaid parking violations.

First, the log of the weighted average distance between a country’s population and the U.S. population is

strongly positively correlated with parking violations, even conditional on world region fixed effects

(Table 6, regression 1), indicating that diplomats from countries physically closer to the U.S. have many

fewer New York City violations. The exact reasons for this pattern are elusive, but greater trade,

migration, and tourism between the countries are possible explanations.

14

The Pew dataset provides a measure of popular attitudes towards the U.S. in a subset of 42

countries, and here we find that diplomats from countries in which popular attitudes are unfavorable are

significantly more likely to have unpaid parking violations (Table 6, regression 2). The estimated effect is

large: a one standard deviation increase in the extent of unfavorable views leads to a more than doubling

of parking tickets. One possible explanation for this result, which would lead to a spurious correlation, is

that individuals in countries that hold negative views about other countries in general also tend to be

corrupt. However, the result remains robust when we include an additional attitude control that reflects

responses to a parallel question on respondents’ dislike of a neighboring country (regression 3). The

coefficient estimate on this additional control is near zero and not statistically significant while the

coefficient estimate on views towards the U.S. remains nearly unchanged and statistically significant at

over 90% confidence. The main limitation of the analysis in regressions 2 and 3 is the small sample size

of only 42 countries

15

, the countries for which there is Pew survey data. In contrast, the association

between the proportion of Muslim population in a country, which is widely thought to be related to anti-

American popular attitudes, is not significantly related to unpaid parking violations (regression 5) whether

or not region fixed effects are included as controls (results not shown).

The relationship between unpaid New York City parking violations and the country corruption

index remains qualitatively similar, but becomes somewhat weaker, during the post-enforcement period

14

Trade with the United States is indeed negatively correlated with diplomats’ parking violations, but this effect

loses statistical significant when we control for geographic distance to the U.S. (results not shown), suggesting there

are other factors beyond trade alone.

15

This decline in sample size is responsible for the loss of statistical significance for the coefficient estimate on

Corruption, which nonetheless remains nearly identical in magnitude to the other specifications.

13

after November 2002 (Table 7, regressions 1 and 2). This is in part because overall levels of parking

violations fell dramatically (Figure 1). The same is true for the Pew measure of unfavorable attitudes

towards the U.S. (regression 3), which remains positively and statistically significantly correlated with

parking violations. Finally, we note that countries that had higher levels of U.S. economic aid show sharp

drops in parking violations after November 2002 (regression 4), although the point estimate on the aid

coefficient was similarly negative even in the pre-enforcement period. Thus it does not appear that the

new policy of linking U.S. foreign aid to unpaid parking tickets appears was an important component of

the decline in violations.

Figure 1 indicates that there was a sharp drop in violations in the months following the September

11

th

, 2001 attacks in New York City, and we find that countries with larger proportions of Muslim

population experience particularly pronounced declines. This finding holds in a specification containing

country and month fixed effects (regression 1), when additional country-specific time trends are included

(regression 2), and with an income control (regression 3). Potential explanations for this result included

the possibility that governments in predominantly Muslim countries exerted greater pressure on their

diplomats to limit violations in order to avoid arousing local ire in New York City, or alternatively that

Muslim diplomats may themselves have wished to be unobtrusive given the surge of anti-Muslim feeling

and violence in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. One further potential explanation – that missions from

predominantly Muslim countries withdrew diplomats for safety reasons – can be ruled out: the U.N.

Bluebook shows no post-9/11 decline in the number of diplomats from predominantly Muslim countries

posted in New York (regression not shown).

Further Robustness Checks and Alternative Explanations

As noted in the introduction, informal or formal social sanction against diplomats in the home country

could be partially responsible for restraining parking violations in some cases. In such cases, diplomats’

behaviors are better interpreted as an indication of their home country’s norms or culture rather than their

own personal values. We acknowledge this possibility but note that this account remains consistent with

14

our interpretation of the level of New York City parking violations as a revealed preference measure of

corruption for government officials from a certain country, in the absence of formal legal enforcement.

Nonetheless, two findings argue against this alternative interpretation as the main driver of our

findings. First, a Lexis-Nexis search of 504 European news outlets (English language or in translation)

using the terms DIPLOMATS and PARKING and NEW YORK yielded only 25 stories during the entire

study period, and these stories were concentrated in just four countries (the United Kingdom, Germany,

France, and Russia). Further, with the exception of several Russian articles, the stories were about the

general problem of diplomatic parking violations in New York City and the 2002 crackdown, rather than

reporting on the behavior of home country diplomats. The possibility of sanctions for returning diplomats

who accumulated parking tickets while abroad is apparently not a leading media issue, in Europe at least.

Second, we considered whether unpaid parking violations early in an official’s tenure at the

United Nations in New York City is correlated with the length of his employment there, and further

whether these early violations interact in any way with corruption in the country of origin (i.e., perhaps

violators from low corruption countries could be punished by their government and sent home early). We

find no evidence for any such effects of parking violations on diplomat tenure (regressions not shown).

Obviously, neither of these two findings is completely conclusive. In equilibrium the number of

violations committed will reflect choices made, in part, to avoid home country sanctions. But they are

certainly consistent with the view that home country enforcement was typically weak or nonexistent.

An additional estimation concern is that our country corruption measure may be picking up an

income effect rather than a corruption effect. Wealthier diplomats could potentially have greater means to

simply pay off any tickets or use parking garages, for example. However, this also seems unlikely. First,

the inclusion of paid violations in our parking violations measure has no effect on the main results

(Appendix Table A2). We also find that the index of country corruption explains unpaid parking

violations even conditional on a linear national per capita income control (and also controlling for the

ratio of bureaucratic wages to per capita income), although our results are attenuated somewhat by the

inclusion of higher order polynomial income controls, as discussed above.

15

Finally, we examined the predictors of the most socially egregious New York City parking

violations, the rationale being that relatively impoverished diplomats from poor countries might be forced

to park illegally in order to avoid the extra expense of renting a parking spot, but might still try to do so in

a manner that avoids excessive negative social externalities. As indications of extreme violations, we in

particular consider parking in front of a fire hydrant, and violations for double-parking on East-West

streets between 10

th

and 100

th

Streets in Manhattan. These are relatively narrow and heavily traveled

roads and double parking will often completely block passage. The main results hold robustly for both

types of violations (Appendix Table A3); in other words, diplomats from high corruption countries are

much more likely to commit the most egregious parking violations. Hence our results are not driven

solely by behaviors causing minimal social harm (i.e., an expired meter in a legal parking spot). Once

again, we acknowledge that these tests cannot conclusively rule out that income is playing some role in

driving the country corruption result, but the weight of the evidence argues against this explanation.

A final consideration is whether there is a differential selection mechanism for U.N. diplomats

across countries that might account for the pattern we observe. In particular, it would problematic if the

relatively more corrupt government officials (within the distribution of officials in a country) were

selected for New York postings from high corruption countries. We have no rigorous statistical test to

explore this possibility, but we feel it is unlikely to be of first-order importance for several reasons. First,

U.N. mission staff are selected along a range of common characteristics, including English-language

skills, education and diplomatic experience, and this reduces the gap between diplomats in terms of their

personal attributes. Further, we are not concerned with differential selection of “corrupt” types into the

government bureaucracy versus the private sector across countries, since we are interested in the behavior

of actual government civil servants, like the U.N. mission diplomats we observe. So any selection story

must pertain to selection across branches of the civil service. To the extent that this selection effect is at

work, we might expect it to operate in the opposite direction. For example, in the Transparency

International 2005 survey of the bureaucracy in Kenya – a reasonably high corruption country –

16

diplomatic missions were rated as the fifth least corrupt among all 34 government ministries.

16

It appears

that, if anything, U.N. postings offer fewer opportunities for graft than many other government positions

(e.g., in customs) and thus might likely attract the relatively less corrupt bureaucrats in high corruption

countries. This would dampen the observed correlation between parking violations and home-country

corruption rather than generating a spurious positive correlation.

5. Conclusion

We exploit a unique natural experiment – the stationing in New York City of thousands of government

officials from 146 countries around the world – in a setting of zero legal enforcement of parking

violations to construct a revealed preference measure of official corruption. We find that this measure is

strongly correlated with existing measures of home country corruption. This finding suggests that cultural

or social norms related to corruption are quite persistent: even when stationed thousands of miles away,

diplomats behave in a manner highly reminiscent of officials in the home country. Norms related to

corruption are apparently deeply engrained, and factors other than legal enforcement are important

determinants of corruption behavior.

The related second empirical finding is the strong negative relationship between affinity for the

United States in the diplomat’s home country and parking violations in New York. This provides real-

world empirical evidence that sentiments matter in economic decision-making in general and for

corruption decisions in particular. One implication of this finding is that government officials’ “feelings”

towards their own nation – for instance, their extent of patriotism, national pride, or strength of national

identity – could also be factors in their corruption decision within the home country.

One important message from our empirical results is that corruption norms are sticky. This result

raises the critical question of whether there are policy interventions that can modify corruption norms

16

This report may be found at http://ww1.transparency.org/surveys/dnld/kenya_bribery_index2005.pdf, accessed

May 5, 2006. Transparency International reports on corruption across branches of government for other countries

can be found at http://www.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/asia_pacific, although to our

knowledge only in the case of Kenya do they explicitly rank diplomats relative to other branches of government.

17

over time. For example, the Bloomberg administration’s enforcement efforts in New York City in 2002

were extremely successful in changing diplomats’ behaviors, and it would be useful to know whether

these changes might additionally have had persistent effects on norms once individuals become

habituated to rule compliant behavior. Such long-run effects of temporary interventions necessarily rely

on a shift in norms (or tastes), and would be consistent with the findings of Di Tella and Schargrodsky

(2003) on the persistent effects of auditing on corruption in Argentina. Unfortunately, our context does

not accommodate this analysis.

Finally, our methodology of inexpensively generating cross-country data could potentially be

applied to other settings where comparable individuals from across countries are present in the same place

for a period of concentrated activity (the Olympics Games, for example). In this spirit, in separate work

we are preparing to study the economic decisions of taxi drivers waiting to pick up passengers at John F.

Kennedy International Airport in New York City. This subject pool similarly provides us with a vast

population of thousands of individuals drawn from societies throughout the world. We hope that this, and

other variants on the methodology, will be useful in informing our understanding of how cultural and

social backgrounds lead to long-run differences in beliefs, tastes, values, and economic decisions.

References

Becker, Gary S., “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach,” Journal of Political Economy,

LXXVI (1968), 169-217.

Chavis, Larry and Phillip Leslie, “Consumer Boycotts: The Impact of the Iraq War on French Wine Sales

in the U.S,” NBER Working Paper No. 11981, 2006.

Council on American-Islamic Relations, “Annual Civil Rights Report 2002: Stereotypes and Civil

Liberties,” http://www.cair-net.org/asp/execsum2002.asp (accessed March 9, 2006).

Di Tella, Rafael, and Ernesto Schargrodsky, "The Role of Wages and Auditing during a Crackdown on

Corruption in the City of Buenos Aires," Journal of Law and Economics, XLVI (2003), 269-292.

Hiscox, Michael and Nick Smyth, “Is there a Demand for Labor Standards? Evidence from Field

Experiments in Social Labeling,” mimeo, Harvard University, 2005.

“Illegal Parking by Diplomats on Rise,” Korea Times, (November 1, 1999).

18

Kang, Sung Won and Hugh Rockoff, “Capitalizing Patriotism: The Liberty Loans of World War I,”

NBER Working Paper No. 11919, 2006.

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi, “Governance Matters IV: Governance Indicators

for 1996–2004,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 3630, 2005.

Kuziemko, Ilyana and Eric Werker, “How Much Is a Seat on the Security Council Worth? Foreign Aid

and Bribery at the United Nations,” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 06-029, 2006.

Lambsdorff, Johann Graf, “Consequences and Causes of Corruption – What do We Know from a Cross-

Section of Countries?” forthcoming in S. Rose-Ackerman and E. Elgar, eds., Handbook of Economic

Corruption (2006).

Mauro, Paolo. (2004). “The Persistence of Corruption and Slow Economic Growth”, IMF Staff Papers

Vol. 51, No. 1.

Mayer, Thierry and Soledad Zignago, “Market Access in Global and Regional Trade,” CEPII Working

Paper 2005-02, 2005.

Pew Charitable Trust, “What the World Thinks in 2002,”

http://pewglobal.org/reports/display.php?ReportID=165 (accessed March 9, 2006).

Schiavo-Campo, Salvatore, Giulio de Tommaso, and Amit Mukherjee, "An International Statistical

Survey of Government Employment and Wages," World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 1806,

1999.

Singleton, Don, “Bill Socks Scofflaw Diplos,” New York Daily News (November 21, 2004), City Final

Edition, pg. 28.

“So what are diplomats immune to?” BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/special_report/1998/10/98/e-

cyclopedia/196677.stm, October 28, 1998.

“Speedy diplomats steer clear of fines in France,” Agence France-Presse, March 16, 2005.

Tirole, Jean. (1996). “A Theory of Collective Reputations (with Applications to the Persistence of

Corruption and to Firm Quality)”, Review of Economic Studies, 63(1), 1-22.

Transparency International, “TI Mission Statement,” http://ww1.transparency.org/about_ti/mission.html

(accessed March 9, 2006).

US Department of State, “International Religious Freedom Report for 2004,”

http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2004/.

Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961, http://www.un.int/usa/host_dip.htm.

Witzel, Morgen, “How to Respond When Only Bribe Money Talks,” Financial Times (July 11, 2005),

London Edition 1, pg 14.

19

Tables and Figures

Table 1: Average Unpaid Annual New York City Parking Violations per Diplomat, 11/1997 to 11/2002

Corruption

rank Country name

Violations per

diplomat

U.N. Mission

diplomats in 1998 Country code

1 KUWAIT 246.2

9

KWT

2 EGYPT 139.6

24

EGY

3 CHAD 124.3

2

TCD

4 SUDAN 119.1

7

SDN

5 BULGARIA 117.5

6

BGR

6 MOZAMBIQUE 110.7

5

MOZ

7 ALBANIA 84.5

3

ALB

8 ANGOLA 81.7

9

AGO

9 SENEGAL 79.2

11

SEN

10 PAKISTAN 69.4

13

PAK

11 IVORY COAST 67.1

10

CIV

12 ZAMBIA 60.4

9

ZMB

13 MOROCCO 60.0

17

MAR

14 ETHIOPIA 59.7

10

ETH

15 NIGERIA 58.6

25

NGA

16 SYRIA 52.7

12

SYR

17 BENIN 49.8

8

BEN

18 ZIMBABWE 45.6

14

ZWE

19 CAMEROON 43.6

8

CMR

20 MONTENEGRO & SERBIA 38.0

6

YUG

21 BAHRAIN 37.7

7

BHR

22 BURUNDI 37.7

3

BDI

23 MALI 37.4

5

MLI

24 INDONESIA 36.1

25

IDN

25 GUINEA 34.8

5

GNB

26 SOUTH AFRICA 34.0

19

ZAF

27 SAUDI ARABIA 33.8

12

SAU

28 BANGLADESH 33.0

8

BGD

29 BRAZIL 29.9

33

BRA

30 SIERRA LEONE 25.6

4

SLE

31 ALGERIA 25.2

13

DZA

32 THAILAND 24.5

13

THA

33 KAZAKHSTAN 21.1

9

KAZ

34 MAURITIUS 20.5

4

MUS

35 NIGER 19.9

3

NER

36 CZECH REPUBLIC 18.9

7

CZE

37 LESOTHO 18.8

6

LSO

38 BOTSWANA 18.5

8

BWA

39 BHUTAN 18.4

5

BTN

40 SRI LANKA 17.2

5

LKA

41 CHILE 16.5

14

CHL

42 TUNISIA 16.5

11

TUN

43 NEPAL 16.5

6

NPL

20

44 IRAN 15.7

20

IRN

45 FIJI 15.5

3

FJI

46 ITALY 14.6

16

ITA

47 LIBERIA 13.5

6

LBR

48 MALAWI 13.0

6

MWI

49 PARAGUAY 13.0

6

PRY

50 RWANDA 12.9

3

RWA

51 UKRAINE 12.9

14

UKR

52 SPAIN 12.7

15

ESP

53 PHILIPPINES 11.5

20

PHL

54 GHANA 11.3

10

GHA

55 MAURITANIA 11.2

5

MRT

56 GUINEA BISSAU 10.8

10

GIN

57 ESTONIA 10.5

3

EST

58 MONGOLIA 10.2

5

MNG

59 ARMENIA 10.1

4

ARM

60 COSTA RICA 10.1

19

CRI

61 COMOROS 9.9

3

COM

62 TOGO 9.9

5

TGO

63 VIETNAM 9.8

15

VNM

64 GEORGIA 9.7

8

GEO

65 CHINA (PRC) 9.5

69

CHN

66 YEMEN 9.1

8

YEM

67 VENEZUELA 9.1

16

VEN

68 PORTUGAL 8.8

16

PRT

69 UZBEKISTAN 8.8

5

UZB

70 MADAGASCAR 8.7

8

MDG

71 TANZANIA 8.3

8

TZA

72 LIBYA 8.2

9

LBY

73 KENYA 7.7

17

KEN

74 CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE) 7.7

6

COG

75 CROATIA 6.5

9

HRV

76 DJIBOUTI 6.5

3

DJI

77 SLOVAK REPUBLIC 6.4

12

SVK

78 FRANCE 6.1

29

FRA

79 INDIA 6.1

18

IND

80 LAOS 6.1

9

LAO

81 TURKMENISTAN 5.8

4

TKM

82 PAPUA NEW GUINEA 5.5

3

PNG

83 HONDURAS 5.4

6

HND

84 SLOVENIA 5.2

8

SVN

85 KYRGYZSTAN 5.2

5

KGZ

86 NICARAGUA 4.9

9

NIC

87 URUGUAY 4.4

11

URY

88 SWAZILAND 4.3

7

SWZ

89 TAJIKISTAN 4.3

4

TJK

90 NAMIBIA 4.2

11

NAM

91 MEXICO 4.0

19

MEX

92 ARGENTINA 3.9

19

ARG

93 SINGAPORE 3.5

6

SGP

21

94 ROMANIA 3.5

10

ROM

95 UGANDA 3.5

7

UGA

96 HUNGARY 3.3

8

HUN

97 MACEDONIA 3.3

4

MKD

98 BOLIVIA 3.1

9

BOL

99 PERU 3.1

9

PER

100 HAITI 3.0

9

HTI

101 JORDAN 2.9

9

JOR

102 BELARUS 2.7

8

BLR

103 BELGIUM 2.7

14

BEL

104 CYPRUS 2.5

11

CYP

105 GUYANA 2.3

5

GUY

106 AUSTRIA 2.2

21

AUT

107 GABON 2.2

8

GAB

108 RUSSIA 2.0

86

RUS

109 LITHUANIA 2.0

7

LTU

110 EL SALVADOR 1.7

10

SLV

111 POLAND 1.7

17

POL

112 GAMBIA 1.5

8

GMB

113 MALAYSIA 1.4

13

MYS

114 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 1.4

6

TTO

115 LEBANON 1.3

3

LBN

116 GERMANY 1.0

52

DEU

117 ERITREA 0.8

3

ERI

118 MOLDOVA 0.7

4

MDA

119 KOREA (SOUTH) 0.4

33

KOR

120 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 0.1

22

DOM

121 FINLAND 0.1

18

FIN

122 GUATEMALA 0.1

9

GTM

123 NEW ZEALAND 0.1

8

NZL

124 SWITZERLAND 0.1

10

CHE

125 UNITED KINGDOM 0.0

31

GBR

126 NETHERLANDS 0.0

17

NLD

127 UNTED ARAB EMIRATES 0.0

3

UAE

128 AUSTALIA 0.0

12

AUS

129 AZERBAIJAN 0.0

5

AZE

130 BURKINA FASO 0.0

5

BFA

131 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 0.0

3

CAF

132 CANADA 0.0

24

CAN

133 COLOMBIA 0.0

16

COL

134 DENMARK 0.0

17

DNK

135 ECUADOR 0.0

9

ECU

136 GREECE 0.0

21

GRC

137 IRELAND 0.0

10

IRL

138 ISRAEL 0.0

15

ISR

139 JAMAICA 0.0

9

JAM

140 JAPAN 0.0

47

JPN

141 LATVIA 0.0

5

LVA

142 NORWAY 0.0

12

NOR

143 OMAN 0.0

5

OMN

22

144 PANAMA 0.0

8

PAN

145 SWEDEN 0.0

19

SWE

146 TURKEY 0.0

25

TUR

23

Table 2: Descriptive statistics

Variable Mean Standard

deviation

Observations

Panel A: Country-level data

Annual unpaid New York City parking violations per diplomat, 11/1997-11/2002

a

2.06 1.41 146

Annual unpaid and paid New York City parking violations per diplomat, 11/1997-11/2002

a

0.28 0.35 146

Annual unpaid New York City parking violations per diplomat, 11/2002-12/2005

a

1.88 1.85 146

log(Diplomats in the country U.N. Mission, 1998)

b

2.21 0.69 146

log(1+Number of license plates registered to the country’s U.N. Mission, 2006)

c

1.97 0.90 146

Country corruption index, 1998

d

-0.01 1.01 146

log(Per capita income, 1998 US$)

e

7.39 1.58 146

Average government wage / Country per capita income, early 1990s

f

2.83 2.38 92

log(Weighted distance between populations)

g

9.11 0.42 146

Proportion Muslim population, 2004

h

0.28 0.37 146

Unfavorable views towards the United States

i

2.23 0.49 42

Unfavorable views towards other countries

i

2.25 0.51 42

Received U.S. economic aid, 1998

j

0.69 0.47 144

Received U.S. military aid, 1998

j

0.63 0.48 144

Panel B: Diplomat-level data

Monthly New York City parking violations, 11/1997-11/2002

a

0.32 0.65 14408

Length of time at the U.N. Mission in New York City (in months)

b

24.98 16.07 14408

Sources:

a

New York City, Parking Violations Database (provided to the authors by the New York City Department of Finance in December 2005).

b

United Nations Bluebook 1998.

c

U.S. Department of State Office of Foreign Missions (provided to the authors by Deputy Director Murray Smith in April 2006).

d

Composite index from Kaufmann et al. (2005), but here higher values indicate more corruption.

e

World Development Indicators (2005).

f

Schiavo-Campo et al. (1999); exact year differs by country.

g

Mayer and Zignago (2005)

h

US Department of State (2004)

i

Pew Global Attitudes Survey 2002.

j

Data from Kuziemko and Werker (2006).

24

Table 3: Country Characteristics and Unpaid New York City Parking Violations (in logs), 11/1997 to 11/2002 (pre-enforcement)

Dependent variable:

log (1 + Annual NYC Parking Violations)

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

log(Diplomats)

0.86*** 1.04*** 0.56 1.28*** 1.12***

(0.24) (0.24) (0.36) (0.31) (0.26)

Country corruption index, 1998

1.04*** 0.56** 0.62** 0.92*** 0.72***

(0.15) (0.24) (0.24) (0.33) (0.25)

log(Per capita income, 1998 US$)

-0.42** -0.36** -0.19 -0.23

(0.16) (0.16) (0.25) (0.19)

log(1 + Diplomatic Vehicles)

0.54**

(0.26)

Average government wage / country per capita income

0.03

(0.11)

Africa region indicator variable

2.92***

(0.67)

Asia region indicator variable

2.23***

(0.72)

Europe region indicator variable

2.30***

(0.66)

Latin America region indicator variable

1.60**

(0.77)

Middle East region indicator variable

2.83***

(0.89)

Oceania region indicator variable

1.99**

(0.91)

Observations

146 146 146 92 146

R

2

0.23 0.26 0.26 0.33 0.34

Mean of dependent variable (s.d.) 3.8 (2.1) 3.8 (2.1) 3.8 (2.1) 3.8 (2.2) 3.8 (2.1)

Notes: OLS regressions, White robust standard errors. Statistically significantly different than zero at 90% (*), 95% (**), 99% (***) confidence.

25

Table 4: Country Characteristics and Unpaid New York City Parking Violations per Diplomat (in logs), 11/1997 to 11/2002 (pre-enforcement) –

alternative specification

Dependent variable:

log (1 + Annual NYC Parking Violations/Diplomat)

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Country corruption index, 1998

0.61*** 0.27* 0.49** 0.38**

(0.08) (0.15) (0.21) (0.17)

log(Per capita income, 1998 US$)

-0.27** -0.08 -0.11

(0.11) (0.17) (0.13)

Average government wage / country per capita income

0.05

(0.08)

Region indicator variables

No No No Yes

Observations

146 146 92 146

R

2

0.19 0.22 0.25 0.32

Mean of dependent variable (s.d.) 2.1 (1.4) 2.1 (1.4) 2.0 (1.4) 2.1 (1.4)

Notes: OLS regressions, White robust standard errors. Statistically significantly different than zero at 90% (*), 95% (**), 99% (***) confidence.

26

Table 5: Unpaid Parking Violations over Time for Diplomats, 11/1997 to 11/2002 (pre-enforcement)

Dependent variable:

log(1 + Monthly NYC Parking Violations)

Any Monthly NYC

Parking Violation

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

Log(Length of time in New York City (in months))

0.083*** 0.185*** 0.185*** 0.147*** 0.146***

(0.020) (0.024) (0.024) (0.015) (0.015)

Log(Length of time in New York City) * Country corruption index, 1998

0.030** 0.026***

(0.014) (0.008)

Month Fixed Effects

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Diplomat Fixed Effects No Yes Yes Yes Yes

Observations

14408 14408 14408 14408 14408

R

2

0.03 0.44 0.45 0.32 0.32

Mean of dependent variable (s.d.) 0.32 (0.65) 0.32 (0.65) 0.32 (0.65) 0.32 (0.65) 0.32 (0.65)

Notes: OLS regressions, White robust standard errors with clustering by diplomat. Statistically significantly different than zero at 90% (*), 95% (**), 99% (***)

confidence. Observations are at the diplomat-month level.

27

Table 6: Unpaid Parking Violations and Proximity to the U.S., U.S. Aid, and Affinity with the U.S., 11/1997 to 11/2002 (pre-enforcement)

Dependent variable:

log (1 + Annual NYC Parking Violations)

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

log(Diplomats) 1.15*** 0.46 0.41 1.11*** 1.13***

(0.25) (0.51) (0.53) (0.27) (0.26)

Country corruption index, 1998 0.72*** 0.72 0.83 0.70*** 0.71***

(0.24) (0.52) (0.56) (0.25) (0.25)

log(Per capita income, 1998 US$) -0.24 -0.46 -0.42 -0.32 -0.23

(0.19) (0.35) (0.36) (0.22) (0.19)

log(Weighted distance of population from U.S.) 1.65***

(0.58)

Unfavorable views towards the U.S. (Pew) 2.55** 2.28*

(1.14) (1.27)

Unfavorable views towards other countries (Pew) 0.57

(0.66)

Received U.S. economic aid -0.70

(0.52)

Received U.S. military aid 0.56

(0.35)

Proportion Muslim population 0.20

(0.47)

Region indicator variables Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Observations 146 42 42 144 146

R

2

0.37 0.47 0.48 0.35 0.34

Mean of dependent variable (s.d.) 3.8 (2.1) 4.4 (2.1) 4.4 (2.1) 3.8 (2.1) 3.8 (2.1)

Notes: OLS regressions, White robust standard errors. Statistically significantly different than zero at 90% (*), 95% (**), 99% (***) confidence.

28

Table 7: Country Characteristics and Unpaid New York City Parking Violations (in logs), 11/2002 to 12/2005 (post-enforcement)

Dependent variable:

log (1 + Annual NYC Parking Violations)

(1) (2) (3) (4)

log(Diplomats) 0.42*** 0.52*** 0.24 0.53***

(0.11) (0.12) (0.29) (0.13)

Country corruption index, 1998 0.30*** 0.33*** 0.41 0.40***

(0.07) (0.11) (0.31) (0.12)

log(Per capita income, 1998 US$) 0.04 0.01 -0.05

(0.09) (0.20) (0.10)

Unfavorable views towards the U.S. (Pew) 1.29***

(0.40)

Received U.S. economic aid -0.53**

(0.23)

Received U.S. military aid 0.08

(0.17)

Region indicator variables No Yes Yes Yes

Observations 146 146 42 144

R

2

0.14 0.24 0.34 0.27

Mean of dependent variable (s.d.) 1.1 (0.9) 1.1 (0.9) 1.3 (0.9) 1.1 (0.9)

Notes: OLS regressions, White robust standard errors. Statistically significantly different than zero at 90% (*), 95% (**), 99% (***) confidence.

29

Table 8: Unpaid New York City Parking Violations and Muslim Population after September 11, 2001

Dependent variable:

log(1 + Monthly NYC Parking Violations)

(1) (2) (3)

Post 9/11 * Proportion Muslim population -0.32** -0.48** -0.32**

(0.15) (0.19) (0.16)

Post 9/11 * log(Per capita income, 1998 US$) -0.007

(0.053)

Country Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes

Month Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes

Country-specific time trends No Yes No

Observations 7493 7493 7493

R

2

0.78 0.82 0.78

Mean of dependent variable (s.d.) 2.7 (1.7) 2.7 (1.7) 2.7 (1.7)

Notes: OLS regressions, White robust standard errors with clustering by country. Statistically significantly different than zero at 90% (*), 95% (**), 99% (***)

confidence. Observations are at the country-month level, for the period December, 1997 – November, 2002.

30

Appendix Table A1: Country Characteristics and Unpaid New York City Parking Violations (in logs), 11/1997 to 11/2002 (pre-enforcement)

– tobit specifications

Dependent variable:

log (1 + Annual NYC Parking Violations)

(1) (2) (3) (4)

log(Diplomats) 0.89*** 1.11*** 1.35*** 1.17***

(0.27) (0.28) (0.35) (0.27)

Country corruption index, 1998 1.19*** 0.63** 1.05** 0.83***

(0.19) (0.29) (0.40) (0.30)

log(Per capita income, 1998 US$) -0.48** -0.22 -0.27

(0.20) (0.31) (0.22)

Average government wage / country per capita income 0.01

(0.11)

Region indicator variables No No No Yes

Observations 146 146 92 146

Mean of dependent variable (s.d.) 3.8 (2.1) 3.8 (2.1) 3.8 (2.2) 3.8 (2.1)

Notes: Tobit specifications. Statistically significantly different than zero at 90% (*), 95% (**), 99% (***) confidence.

31

Appendix Table A2: Total New York City Parking Violations, paid and unpaid (in logs), 11/1997 to 11/2002 (pre-enforcement)

Dependent variable:

log (1 + Annual NYC Parking Violations)

(1) (2) (3) (4)

log(Diplomats) 1.00*** 1.12*** 1.38*** 1.19***

(0.21) (0.21) (0.28) (0.22)

Country corruption index, 1998 0.96*** 0.62*** 1.14*** 0.73***

(0.15) (0.22) (0.31) (0.23)

log(Per capita income, 1998 US$) -0.29** 0.05 -0.14

(0.15) (0.24) (0.17)

Average government wage / country per capita income 0.15**

(0.07)

Region indicator variables No No No Yes

Observations 146 146 92 146

R

2

0.27 0.29 0.45 0.41

Mean of dependent variable (s.d.) 4.1 (1.8) 4.1 (1.8) 4.2 (1.9) 4.1 (1.8)

Notes: OLS regressions, White robust standard errors. Statistically significantly different than zero at 90% (*), 95% (**), 99% (***) confidence.

32

Appendix Table A3: New York City Parking Violations (in logs), egregious violation types, 11/1997 to 11/2002 (pre-enforcement)

Dependent variable:

log (1 + Annual Cross-town Double-parking)

Dependent variable:

log (1 + Annual Fire Hydrant Violations)

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

log(Diplomats)

0.48*** 0.55*** 0.68*** 0.62*** 0.74*** 0.85*** 0.94*** 0.92***

(0.15) (0.15) (0.21) (0.17) (0.16) (0.16) (0.22) (0.17)

Country corruption index, 1998

0.43*** 0.24* 0.40** 0.30* 0.62*** 0.30** 0.50** 0.42**

(0.08) (0.13) (0.18) (0.15) (0.09) (0.15) (0.21) (0.18)

log(Per capita income, 1998 US$)

-0.17* -0.09 -0.11 -0.27** -0.15 -0.20

(0.09) (0.15) (0.11) (0.11) (0.16) (0.13)

Average government wage / country per capita income

0.03 0.01

(0.06) (0.06)

Region indicator variables

No No No Yes No No No Yes

Observations

146 146 92 146 146 146 92 146

R

2

0.14 0.16 0.22 0.27 0.23 0.26 0.32 0.34

Mean of dependent variable (s.d.)

1.1 (1.2) 1.1 (1.2) 1.1 (1.2) 1.1 (1.2) 1.7 (1.4) 1.7 (1.4) 1.7 (1.4) 1.7 (1.4)

Notes: OLS regressions, White robust standard errors. Statistically significantly different than zero at 90% (*), 95% (**), 99% (***) confidence.

33

Figure 1: Total Monthly New York City Parking Violations by Diplomats, 1997-2005 (log scale)

1

10

100

1,000

10,000

Monthly Unpaid Parking Violations

11/1997 9/2001 11/2002 11/2005

9/11 Attacks

Increase in

Enforcement

34

Figure 2: Country corruption and Unpaid New York City Parking Violations per diplomat (in logs), 11/1997 to 11/2002 (pre-enforcement)

KWT

EGY

TCD

SDN

BGR

MOZ

ALB

AGO

SEN

PAK

CIV

ZMB

MAR

ETH

NGA

SYR

BEN

ZWE

CMR

YUG

BHR

BDI

MLI

IDN

GNB

ZAF

SAU

BGD

BRA

SLE

DZA

THA

KAZ

MUS

NER

CZE LSO

BWA

BTN

LKA

CHL TUN NPL

IRN

FJI

ITA

LBR

MWI PRY

RWA UKR

ESP

PHL

GHA

MRT

GIN

EST

MNG

ARM

CRI

COMTGO

VNM

GEO

CHN

YEMVEN

PRT UZB

MDG

TZALBY

KEN

COG

HRV

DJI

SVK

FRA IND LAO

TKM

PNG

HND

SVN KGZ

NIC

URY

SWZ TJK

NAM

MEX

ARG

SGP

ROM

UGA

HUN

MKD

BOLPER

HTI

JOR

BLR

BEL

CYP

GUY

AUT GAB

RUSLTU

SLV

POL

GMB

MYS

TTO

LBN

DEU

ERI

MDA

KOR

DOMFIN

GTM

NZL

GBR

NLD

AREAUS AZEBFACAFCAN COLDNK ECUGRCIRL ISR JAMJPN LVANOR OMN PANSWE TUR

0 2 4 6

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Country corruption measure

NYC Violations/Diplomat (logs) Fitted values

Notes: Country abbreviations are presented in Table 1. The line is the quadratic regression fit. The y-axis is log(1+Annual NYC parking violations / Diplomat).

35

Data Appendix

(1) New York City Diplomatic Parking Violation Data

The New York City Department of Finance supplied listings of all unpaid parking violations of U.N.

Missions. The violations covered the period from November 24, 1997 to November 21, 2005. In order to

appear in the database, a violation had to go unpaid for at least 100 days. Data were at the level of the

violation, and included the following entries for each violation:

• Summons: unique identification number for the violation

• License plate number of the violating car

• The person to whom the violating car was registered, often the mission itself

• Time of violation: included both hour and minute as well as calendar date

• Type of violation, e.g. “FIRE HYDRANT” or “EXPIRED METER”

• Street address of violation

• Initial dollar value of fine issued

• Additional dollar penalty for having not paid the fine on time

• Amount paid towards the fine, generally zero

• Name of country to which the car is registered

Data on U.N. diplomats’ paid parking violations (violations that did not go into arrears) were made

available to us in aggregate form by the New York City Department of Finance. For each country, we

were given statistics for the pre-enforcement period of November 24, 1997 – October 31, 2002 and the

post-enforcement period of November 1, 2002 – November 21, 2005.

(2) Country Corruption Index

We use the aggregate measure of Kaufmann et al (2005) for the year 1998. Data are available at:

http://www.worldbank.org/wbi/governance/data.html#dataset

(3) World Region Classification

United Nations region code data, available at http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm, was

used to classify countries into the following regions: (1) North America (including Carribbean), (2) South

America, (3) Europe, (4) Asia, (5) Oceania, (6) Africa, (7) Middle East. The Middle East was defined as:

Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Occupied Palestinian

Territory, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

(4) International Trade Data

Trade data (utilized only in unreported regressions) are taken from http://dataweb.usitc.gov/

(5) Geographic Distance From U.S.

Distance from the United States is taken from Mayer and Zignago (2005). Their measure uses city-level

data to assess the geographic distribution of population inside each nation. The idea is to calculate

distance between two countries based on bilateral distances between the largest cities of those two

countries, those inter-city distances being weighted by the share of the city in the overall country’s

population. In practice, nearly identical results are obtained using the distance of countries’ capitals from

Washington, D.C.

(6) United Nations Bluebooks

The United Nations issues its list of mission personnel, or Bluebook, twice yearly. We utilize edition

numbers 280 (May 1998) through 288 (August 2002). Documents were retrieved from the UN Official

Document System (ODS), available at http://documents.un.org/advance.asp. Searching for the symbol

36

ST/SG/SER.A/### with truncation turned off returns the relevant Blue Book (where ### is the Blue Book

edition number).

(7) Mission Staff Counts

Edition 280 (May 1998) was checked by hand to count the mission staff and spouses for each country in

the Blue Book, producing the following variables.

• Mission: Indicator variable indicating whether the country had a U.N. mission

• Staff: Simple count of staff. Staff members are always listed with their surnames in bold

(8) Longitudinal Staff Data

Bluebook edition numbers 278 through 288 were converted into plain text format. A name-matching

program then checked these text files against a list of names extracted from the NYC parking violations

data. Names were converted to regular expressions to improve match quality (since names from parking

violation data often used forward slashes in place of apostrophes and dashes). A name was considered to

have matched (and thus to have been present at the date of the Bluebook’s publication) if its first name

and last name appeared on the same line in the Bluebook. If a name matched more one time in the same

Blue Book, its matches were checked by hand. The matching program also recorded the country of the

mission in which the match was found. This country was checked against the country as specified by the

parking violation data to verify match accuracy. Finally, in a small number of cases (20 diplomats), we

found that there were gaps in the individual’s appearance in the Blue Book, even though in some cases