Minnesota State University Moorhead Minnesota State University Moorhead

RED: a Repository of Digital Collections RED: a Repository of Digital Collections

Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies

Summer 6-23-2021

Effects of Play-Based Learning on Phonemic Awareness and Effects of Play-Based Learning on Phonemic Awareness and

Phonics Skills Phonics Skills

Kristen Heidecker

Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis

Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, and the

Elementary Education Commons

Researchers wishing to request an accessible version of this PDF may complete this form.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Heidecker, Kristen, "Effects of Play-Based Learning on Phonemic Awareness and Phonics Skills" (2021).

Dissertations, Theses, and Projects

. 481.

https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/481

This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a

Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an

authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact

Effects of Play-Based Learning on Phonemic Awareness and Phonics Skills

A Project Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead

By

Kristen Heidecker

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Curriculum and

Instruction

May 2021

Moorhead, Minnesota

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES ...........................................................................................................................4

ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................5

DEDICATION .................................................................................................................................6

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................7

Introduction ..........................................................................................................................7

Statement of the Problem .....................................................................................................8

Purpose of the Study ............................................................................................................9

Research Question(s) ...........................................................................................................9

Definition of Variables .....................................................................................................10

Significance of the Study ...................................................................................................10

Research Ethics ..................................................................................................................11

Permission and IRB Approval ...............................................................................11

Informed Consent...................................................................................................11

Limitations .............................................................................................................12

CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction ........................................................................................................................13

Body of the Review ...........................................................................................................13

Context ...............................................................................................................................13

Play-Based Learning .............................................................................................13

Early Literacy ........................................................................................................15

Theoretical Framework ......................................................................................................16

Conclusions ........................................................................................................................18

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

3

CHAPTER 3. METHODS

Introduction ........................................................................................................................19

Research Question(s) .........................................................................................................19

Research Design.................................................................................................................19

Setting ................................................................................................................................20

Participants .........................................................................................................................20

Sampling ............................................................................................................................20

Instrumentation ..................................................................................................................21

Data Collection ......................................................................................................21

Data Analysis .........................................................................................................22

Research Question(s) and System Alignment........................................................22

Procedures ..........................................................................................................................22

Ethical Considerations .......................................................................................................23

CHAPTER 4 ..................................................................................................................................24

CHAPTER 5 ..................................................................................................................................29

REFERENCES ..............................................................................................................................31

APPENDIX A ................................................................................................................................35

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

4

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Word Segmenting ................................................................................................26

Table 2: Letter Sounds .......................................................................................................26

Table 3: Sight Words .........................................................................................................27

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

5

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this research was to determine the effectiveness of play-based learning on

phonemic awareness and phonics skills in kindergarten. This study aimed to determine whether

or not play-based learning materials such as letter tiles, cards, timers, and literacy-based games

were an effective way for kindergarten students to acquire skills such as segmenting, letter

sounds, and sight word recognition. A pre-assessment was given using FastBridge to determine

which skills the students were working towards mastering. Play-based learning materials were

then offered to small groups of students during our regular literacy time, and data was collected

using FastBridge after two weeks of implementation. After analyzing the data, it was determined

that play-based learning was in fact an effective way for the kindergarten students to acquire

phonemic awareness and phonics skills.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

6

DEDICATION

It is with a grateful heart that I dedicate this action research study to my husband Mike,

our two boys, Mason and Sam, and my family and friends. Your support, patience, and

encouragement went above and beyond anything I could have ever imagined. You all rock, I

love you.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

7

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Introduction

In kindergarten classrooms today, as rigorous standards are pushed-down, teachers are

expected to foster child-development, ensure standards are met, all while trying to keep activities

developmentally appropriate. One could go as far to say that kindergarten has become what used

to be 1

st

grade. The focus has shifted from child-centered to academic-centered, and so has

pedagogy. The lens continues to zoom in on standards, assessments, and boxed curriculum,

while child development and developmentally appropriate practices have been shifting out of

focus in kindergarten. There can and should be a balance between academics and play, and also

a way to intertwine the two.

The kindergarten classroom that most adults remember from their childhood, with plenty

time for unstructured play, art and music, practicing social skills, discovery, and learning to

enjoy learning-has largely disappeared (Almon & Miller 2009). With increasing accountability

in kindergarten, teachers need to ensure that students reach certain literacy milestones before

proceeding to the subsequent grade. One result of this shift is a tension between an emphasis on

academic learning, and the use of developmentally appropriate practices, such as play (Pyle et

al., 2018). Child development has not changed, and yet, more and more academic pressure is

being placed on our youngest learners. The demands that students will face in the years to come

in school are great, therefore students need to build a solid foundation of early literacy skills. As

an early childhood educator, it is crucial to implement developmentally appropriate and engaging

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

8

activities for students. This has led me to the question the effects of play-based learning on

phonemic awareness and phonics skills.

The research written about play-based learning suggests that there are benefits in using

this approach when teaching literacy skills. According to a research study on the play-literacy

interface in kindergarten, “while play has been shown to benefit children’s development and

learning, different play contexts, such as free play and guided play, have been found to better

support children’s development and their academic learning” (Pyle et al., 2018, p.118).

Although it is not an easy task to incorporate play-based learning, it is developmentally

appropriate, more engaging, and children deserve it.

In a study conducted by Moore (2020) it was found that play-based learning was an

effective strategy in teaching phonemic awareness and phonics when taught with an adult

facilitator. When students were part of creating the rules for a game or activity, they were more

engaged and participated more. It was found that students also learn cooperating, problem-

solving, and early literacy skills through guided play. With differing academic levels, students

were able to both teach and learn from each other while playing, and play-based learning can be

used along with current classroom routines and curriculum (Moore, 2020).

Statement of the Problem

The research problem is to measure whether or not play-based centers are an effective

way for children to learn phonemic awareness and phonics skills. The reading curriculum that

the district has adopted is not developmentally appropriate, or engaging for the kindergarten

students. Much of the curriculum involves skill and drill worksheets, and letter of the week

activities, both practices that I found in my experience teaching kindergarten to be ineffective. It

is also missing the phonemic awareness and phonics instruction piece. It is important for

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

9

kindergarten students to develop a strong foundation of literacy skills in order to become

successful readers. Of equal importance is ensuring that the students are engaging in

developmentally appropriate activities while building these skills.

Purpose of the Study

Prior to the implementation of play-based literacy centers, a mix of a boxed curriculum

and the Daily 5 approach, a literacy framework based on 5 areas of literacy including word work,

listen to reading, work on writing, read to self, and reading to someone, were used. These

approaches were unsuccessful in keeping the students engaged. The play-based center approach

that has been slowly implemented over the course of the last year focuses on the phonemic

awareness and phonics skills that are taught to the students during whole group and mini lessons.

These skills include segmenting and blending words, letter sounds, word family recognition,

CVC words, and sight word recognition. Now that the materials and routines have been

established, it is important to know if this play-based strategy is an effective way for students to

acquire phonemic awareness and phonics skills.

After conducting the fall benchmarking assessments using FastBridge, an online

assessment system tool used for benchmarking and progress monitoring students, it was found

that 40% of the kindergarten students were not meeting proficiency in early literacy skills. The

district goal is for 80% of students to be meeting or exceeding by spring. These scores prompted

a deeper look into the effectiveness of the strategies and pedagogy being implemented in the

kindergarten classroom. The goal is to increase the student’s phonemic awareness and phonics

skills by using developmentally appropriate, engaging, play-based activities.

Research Question(s)

What are the effects of play-based learning on phonemic awareness and phonics skills?

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

10

Definition of Variables.

The following are the variables of study:

Variable A: Early literacy skills, specifically phonemic awareness and phonics skill

acquisition will be the dependent variable in the action research study. Early literacy skills are

defined as the skill set that students need in order to transition from learning to read, to reading

to learn. The skills include vocabulary, phonics, language, and numeracy, and give students the

foundation they need in order to learn and grow (Renaissance Learning, Inc., 2020). The early

literacy skills that will be focused on in this study are word segmenting and blending, letter

sounds, CVC words, and sight word recognition.

Variable B: Teacher guided, play-based learning games in the areas of phonemic

awareness and phonics will be the independent variable. The term “teacher guided play” refers

to play activities that involve some level of adult involvement to embed or extend additional

learning opportunities within play (Pyle & Danniels, 2018). A range of terminology has been

used when referring to guided play, for example, center-based learning, or purposefully framed

play (Pyle & Danniels, 2018). Phonemic awareness and phonics play-based centers will be used

that are specific to the skill that each child is working toward mastering. For example, if the

student is not yet able to segment sounds in a word, they were given a play-based literacy center

that is specifically working on that skill. Letter tiles, play dough, picture cards, and board games

are some examples of the play-based materials the students will use.

Significance of the Study

Early childhood educators today face the challenge of trying to integrate mandated

academic standards, while keeping activities developmentally appropriate. Studies have shown

that guided play is indeed effective at allowing children to learn. “Specifically, research has

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

11

found that children who engaged in guided play activities were more likely to learn a target piece

of information than children who engaged in free play---and in some cases, more than children

who were directly instructed” (Weisberg & Zosh, 2018, p. 27). As more focus is placed on

academics in the early childhood years, children are being robbed of play to ensure academic

benchmarks are met. A strong foundation of early literacy skills is vital, however, children need

to be given the opportunity to acquire these skills using a play-based approach. This has been an

internal struggle over the last few years, and it is why it was chosen to as the topic of research.

Research Ethics

Permission and IRB Approval. In order to conduct this study, I recieved approval from

MSUM’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure the ethical conduct of research involving

human subjects (Mills & Gay, 2019). Likewise, authorization to conduct this study was sought

from the school district where the research project took place, at a small rural school in West

Central Minnesota.

Informed Consent. Protection of human subjects participating in research was assured.

Participant minors were informed of the purpose of the study via the Informed Consent Letter. I

also read the method of assent to the participants before beginning the study. Participants were

made aware that this study was conducted as part of the researcher’s Master Degree Program and

that it was intended to benefit the researchers teaching practice. Informed consent means that the

parents of participants were fully informed of the purpose and procedures of the study for which

consent was sought, and the parents understood and agreed, in writing, to their child participating

in the study (Rothstein & Johnson, 2014). Confidentiality was protected through the use of

pseudonyms (e.g., Student 1) without the utilization of any identifying information. The choice

to participate or withdraw at any time was outlined both verbally and in writing

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

12

Limitations.

There were two major limitations in this study, one of them being the group sample size.

The sample size is very small, which made it hard to generalize findings to a larger population.

The second limitation was the diversity, or lack thereof, in this particular group of students. The

group of students in the sample were all Caucasian, English speaking students, and only one of

which was on an IEP for cognitive restrictions. This particular group of students was able to

grasp new concepts more quickly overall than previous groups of students I have taught. The

number of students receiving tier 2 instruction, or that needed to be re-taught concepts, is less

than in previous years. This could lead to higher scores not necessarily related to the play-based

strategy. My own personal bias towards the use of play-based learning could also be a

limitation.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

13

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

Child development has not changed, and yet, we are asking more of our students and

using programs and tools that are not appropriate for their age. Some would argue that the

increased focus on direct instruction is developmentally inappropriate, because children are

being expected to learn academic content that may be beyond their developmental level, in a

manner that does not actively engage students (Pyle & Danniels, 2016). Early childhood

teachers face the challenge of meeting standards and goals to prepare students, while delivering

instruction in a way that is play-based so that it remains developmentally appropriate for

students.

Having a solid foundation of early literacy skills is crucial for students to build upon, and

it is possible to intertwine learning with play. Boxed curricula often rely heavily on skill and

drill worksheets, and while some students are able to learn and grow, they do not meet the

developmental needs of kindergarten children. The districts grade level goals are taken very

seriously, however, play is also a priority in the kindergarten classroom. “We owe children the

chance to be children, and we have to protect this time in their life because they cannot do it for

themselves” (Barsness, 2017, p.5). I am focusing on finding a way to get my students to achieve

our district goals in reading, while using a play-based, teacher guided play approach.

Play-Based Learning

Kindergarten was originally designed as a child-centered program, with playful context

for children to grow and develop (Froebel 1967). In 1837 when Friedrich Froebel founded

kindergarten, or what he referred to as “the children’s garden,” he introduced the idea of

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

14

kindergarten as a place where children’s natural inclination of play could be nurtured (Pyle et al.,

2017). However,

Since the enactment of No Child Left Behind legislation, the early childhood classroom

has changed dramatically. The kindergarten classroom that was once filled with free

play, exploration, and imagination at the forefront of learning has now dissipated into a

classroom virtually devoid of play (Miller and Almon, 2009 as cited in Cavanaugh et al.,

2016, p.832).

Play has long been a topic of research and study in the field of early childhood education. Piaget

and Vygotsky both offered strong research in the area of play, including the effects of play on

language and early literacy skills (Christie & Roskos, 2011). Vygotsky emphasized the social

interactions between individuals as the sources for building literacy knowledge (Tsao, 2008).

Piaget viewed play as integral to the development of intelligence in children. His theory of play

argues that as the child matures, their environment and play should encourage further cognitive

and language development (Hamid, 2018).

Play-based learning is, essentially, to learn while at play (Danniels & Pyle, 2018).

While play has been shown to benefit children’s development and learning, different types of

play better support different types of learning and development (Pyle et al., 2017). Studies that

have been conducted on the benefits of play-based learning have typically focused on two types

of play, free play and guided play (Danniels & Pyle, 2018).

Free play, which is directed by the children themselves, typically involves imaginative

play through role-playing, creating, and following social rules such as pretending to be different

family members (Danniels & Pyle, 2018). Children’s language, cognitive, social, and emotional

development are typically nurtured during free play (Pyle et al., 2017). Guided play, however,

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

15

has some level of adult involvement to extend additional learning within the play itself (Danniels

& Pyle, 2018). In research done by both Fisher et al. (2013) and Weisberg et al. (2013) it was

found that guided play has been found to better support children’s academic learning (Pyle et al.,

2017). There are two types of play within guided play, teacher directed and mutually directed,

and the distinction between the two comes down to who has control over the play. Teacher

directed typically involves intentionally planned games, where mutually directed allows both

students and teachers to exercise some control over the play that is taking place (Danniels &

Pyle, 2018). According to Weisberg and Zosh (2018) guided play should be scaffolded by an

adult, while allowing the child’s actions to lead them to the learning goal, and children should

maintain the locus of control.

Children are innately drawn to play. “Children in play-based kindergartens have a double

advantage over those who are denied play: they end up equally good or better at reading and

other intellectual skills, and they are more likely to become well-adjusted healthy people” (Miller

& Almon, 2009, p.8). It was also found that guided play-based opportunities serve as an

effective way for children to be engaged in the learning process (Weisberg, et al. 2013, as cited

by Cavanaugh et al., 2016). This action research focused on using guided play to acquire and

enhance phonemic awareness and phonics skills.

Early Literacy

The years from birth to five are the most important years for emergent literacy

development, although children do not usually learn to read until the ages of five or six (Elliot &

Olliff, 2008). Research has shown that the learning that occurs during kindergarten regarding

early literacy skills has a significant impact on later academic achievement (McCelland et al.,

2006). As cited by Campbell and Cook, (2008), evidence from the National Reading Panel

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

16

(NRP, 2000) along with work done by the National Research Council committee on Preventing

Reading Difficulties in Young Children (Snow et al., 1998) found that explicit systematic phonics

instruction enhances a student’s ability to learn to read, with the strongest effects of this being in

kindergarten and first grade.

According to the National Research Panel (2002) some literacy skills are more important

than others when it comes to predicting later literacy development. Alphabetic knowledge,

phonological awareness, phonological memory, rapid automatic naming, and letter writing are

listed to have the most impact on children’s reading ability (Gozali-Lee & Mueller, 2013). In

similar findings, according to research done by Elliot and Olliff (2008), in order to be successful

in learning to read, prereaders should have knowledge of the alphabet, phonological awareness,

letter-sound correspondences, awareness of print concepts, and some experience using writing as

a form of communication.

The correlation between children’s literacy development and play has much been studied,

and as a result, has prompted more research to be done over the last few decades (Tsao, 2008).

“By engaging in joyful play activities, children also build meaning or understanding, and

develop skills closely associated with reading and writing competence” (Tsao, 2008, p.515-16).

In my experiences, children are far more engaged in play-based activities in the classroom versus

skill and drill seatwork.

Theoretical Framework

Constructivists believe that individuals learn best when they are actively constructing

new meaning of new concepts. This learner-centered approach requires the learner to take

responsibility in the learning process, while the teacher or instructor plans and designs activities

that encourage active engagement (Clark, 2018). The constructivism theory is also based on the

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

17

idea that learners process or construct new information by relating it to existing information, or

schema (Clark, 2018).

Jean Piaget, well known for his theory of cognitive development, explained how a child

constructed a mental model of the world. He disagreed with the idea that intelligence was a

fixed trait and regarded cognitive development as a process which occurs due to biological

maturation and interaction with the environment (McLeod, 2018). He was the first psychologist

to make a systematic study of cognitive development (McLeod, 2018). Piaget believed that

children take an active role in the learning process. They often naturally act much like little

scientists as they perform experiments, make observations, and learn about the world. As

children interact with the world around them, they add new knowledge, build upon existing

knowledge, and adapt previously held ideas to accommodate new information (Cherry, 2019).

Another well-known researcher, Lev Vygotsky, whose work has become the foundation

of much research and theory in cognitive development over the past several decades, believed in

the sociocultural theory (McLeod, 2018). Vygotsky believed that social interaction helped the

learner create deeper meaning of content, and that learning occurs best when the learner is able

to be in the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) with support from others more knowledgeable

(Clark, 2018).

Constructivists also believe that the learner must take responsibility in the learning

process, rather than playing a passive role and expecting knowledge to sink in (Clark, 2018).

Rather than the teacher telling the child what it is they need to know, the teacher plays the role of

the facilitator, creating activities appropriate for the child’s specific needs to help build on the

skills they already have, and being there to guide the child along the way.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

18

Conclusions

Children learn best while at play. While there are benefits to all different forms of play,

guided play has been found to be an effective approach when working with children on

mastering targeted academic skills. Over the years, standards and academic curriculums have

been pushed down into kindergarten. While it is important to help students learn the early

literacy skills that are embedded in the academic standards, it should be done so in a

developmentally appropriate way, such as play-based learning. Using the information from the

literature, along with the action research, will help determine what the effects play-based

learning has on those essential skills in kindergarten.

The next chapter will look at the research design, participants, data collection, analysis,

alignment, and procedures of the action research study.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

19

CHAPTER 3

METHODOLOGY

Introduction

This study was looking at the effects of play-based learning on phonemic awareness and

phonics skills. In a time when there are more academic demands on children in kindergarten

than ever before, combining learning with play is a logical solution to fit it all in. “An increasing

societal focus on academic readiness (promulgated by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001)

has led to a focus on structured activities that are designed to promote academic results as early

as preschool, with a corresponding decrease in playful learning” (Yogman et. al, 2018, p.2).

Research has shown for years that play is beneficial for children. I questioned whether or not my

students would acquire the phonemic awareness and phonics skills necessary to learn to read,

through play-based learning.

Research Question(s)

What are the effects of play-based learning on phonemic awareness and phonics skills in

kindergarten?

Research Design

According to Fraenkel et al. (2015), the single subject research design best fit my action

research study. This design is “most commonly used to study the changes in behavior an

individual exhibits after exposure to an intervention or treatment of some sort” (Fraenkel et. al,

2015, p. 302). Each student was given play-based materials centered on the phonemic awareness

or phonics skill they were working towards mastering, and I utilized the A-B approach for data

collection. A baseline assessment was given to each student which gave me the information I

needed to assign the play-based center according to the student’s specific needs. A range of

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

20

skills from segmenting words, letter sounds, and sight word recognition were the skills my

students were working towards mastering. Play-based literacy games (IV) were implemented for

two weeks, and a post assessment was given to measure for growth of that specific skill. I

utilized the graph data in FastBridge to calculate the changes from start to finish for each student

in my action research study sample.

Setting

The setting of this study was a small, rural school in West Central Minnesota. It is an

agricultural community with a population of around 500. School enrollment was 282 students in

preschool-12

th

grade with all students in one building. Of the students enrolled, 95.4% were

Caucasian, 3.2% Black or African American, 3.9% American Indian, 3.5 % Hispanic or Latino,

11.3% were in special education, and 36.1% received Free and Reduced Lunch.

Participants

The population in my kindergarten classroom for the 2020-21 school year was composed

of 20 students ages five and six years old, with eleven girls (55%) and nine boys (45%). All 20

(100%) of the students were Caucasian, with one (5%) of the students on an IEP for cognitive

restrictions. Of the 20 students 6 (30 %) qualified for Free and Reduced Lunch.

Sampling

The sample for this action research study was 15 kindergarten students in my classroom.

The students were a purposive sample because they were the students assigned to my class

roster. My research of the effectiveness of play-based learning on phonemic awareness and

phonics skills was directly related to and affected all of the students in my classroom.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

21

Instrumentation

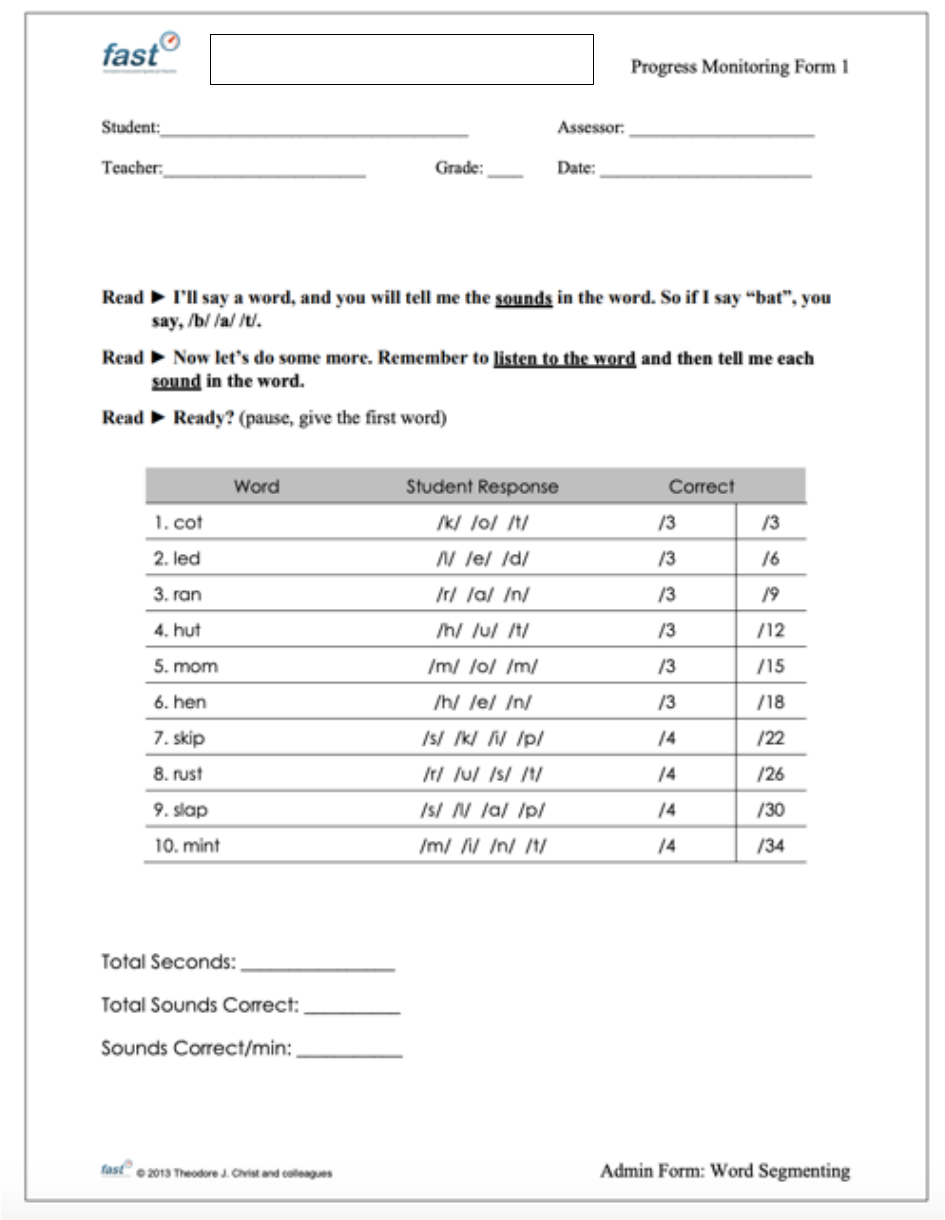

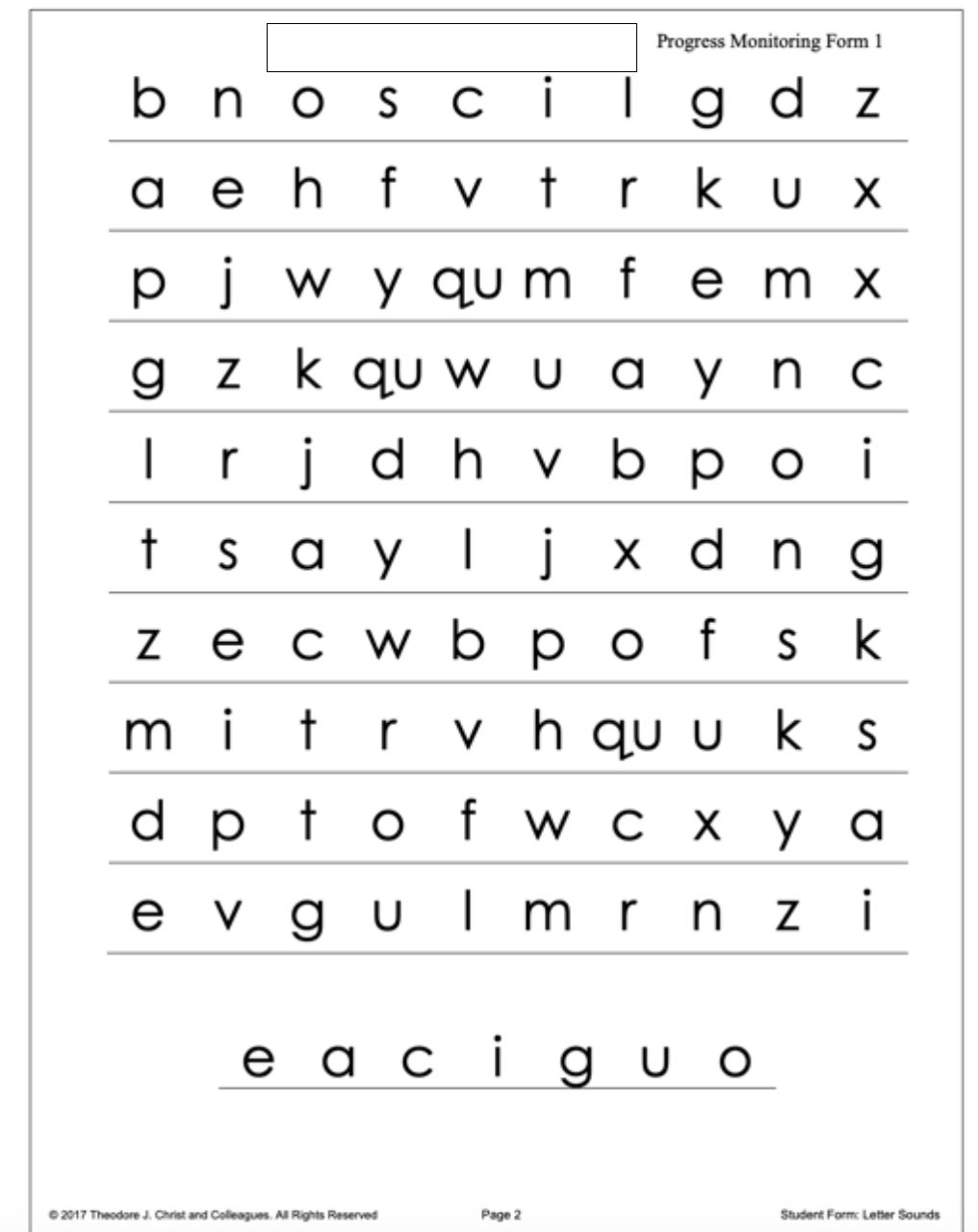

The instrument that I used for data collection was from FastBridge Learning (see

appendix A). FastBridge is an online assessment tool that is used for benchmarking both math

and reading in Fall, Winter, and Spring. FastBridge also offers progress monitoring tools, and

for this action research the phonemic awareness and phonics progress monitoring tools were

used (see Appendix A). The progress monitoring assessments are one-minute timed assessments

that can be given to students weekly. The students were shown the paper copy, while the teacher

was logged into FastBridge to access assessment directions, document any errors, and to stop and

start the timer. Some of the skills for progress monitoring in kindergarten included word

segmenting, letter sounds, and sight words. See appendix A for samples of the both student and

administrator forms.

Data Collection.

To assess the effectiveness of play-based learning on phonemic awareness and phonics

skills, a baseline assessment was given using FastBridge. For the baseline assessment, students

were assessed on their early literacy skills including word blending and segmenting, letter

names, letter sounds, and sight word recognition. In order to accurately assign materials, data

from the assessment (see appendix A) was used. After two weeks of implementation using play-

based learning materials to build phonemic awareness and phonics skills, the students were given

a progress monitoring assessment depending on the skill they were working towards mastering,

i.e. word segmenting, letter sounds, or sight word recognition. I then used the data produced by

FastBridge in the form of graphs to collect data on each student’s progress to be entered into an

excel form.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

22

Data Analysis.

Using an excel spreadsheet, each students’ baseline assessment score, along with their

progress monitoring scores were entered, and the changes made from baseline to progress

monitoring were calculated and recorded in excel as well. I then calculated the mean growth

change in each table. I utilized all of this information to determine if the play-based learning

materials were effective in phonemic awareness and phonics skill acquisition.

Procedures

The action research study took place during our regular literacy center time, between the

times of 9:00-10:35 each morning. From the data collected on the baseline assessment, I

gathered premade phonemic awareness and phonics play-based centers, letter tiles, timers, dice,

and sight word cards that were specific to the skills that each student was working on. For

example, the student working on segmenting sounds was offered a play-based literacy center

with gumball machines and gumballs with pictures for sorting the number of sounds. He was

also offered a magnetic wand, magnetic chips, and sound cards to play with. The students

working on letter sounds were offered a CVC word building game, letter cards, and a timer and

were given the choice of how to use the materials. The students working on sight words were

offered a sight word game, sight word cards, and a timer. Each group was allowed to play,

explore, and engage with the materials at their own pace and in their own way. As the students

were engaging in their play-based literacy centers, I was observing, taking notes, and available to

answer questions and aid in scaffolding my students learning. Each round of centers lasted for

15-20 minutes from set-up to clean-up. The students were assigned the play-based literacy

center for one of their three rounds of centers for that day. I was able to implement, observe, and

monitor progress for two weeks

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

23

Ethical Considerations

An informed consent letter was sent home to the families of my students. Since my

participants were only five and six years old, not only was it important for families to be aware

of what was taking place in our classroom, I wanted to give them the opportunity to make their

own decision on whether or not their child would participate. This study was not in violation of

ethical practice, and I ensured confidentiality in my research data. I did not force any of my

students to answer questions they were not able or capable of answering. Participation in this

study presented no greater harm than that of a normal school day.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

24

CHAPTER 4

DATA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

What are the effects of play-based learning on phonemic awareness and phonics skills?

The purpose of my research was to determine whether or not play-based learning is

effective in acquiring phonemic awareness and phonics skills. After collecting baseline data

from the winter benchmark in FAST Bridge Learning, play-based learning materials were

gathered according to the phonemic awareness and phonics skills that each student needed

improvement on. Letter cards, CVC letter tile word games, sight word cards, dice, timers,

picture cards, magnetic wands, and magnetic chips were the materials gathered. Fifteen of my

twenty students participated in the study, four students were receiving services from a Reading

Corps tutor and/or our Title I program targeting the same skills, and one student was gone for

one week on vacation during data collection. For fidelity purposes, those students were not

included in the data. The play-based learning materials that were specific to each students’ needs

were implemented during our classroom literacy center time with small groups of students with

like needs. After two weeks, the progress monitoring tool from FastBridge Learning was used to

check for growth in word segmenting, letter sounds, and sight word recognition.

During our classroom literacy center time, play-based learning had already been

established, but not specifically to each student’s phonemic awareness or phonics skills needs.

The play-based centers were targeting the skills being taught that week (i.e. word families, with

games and materials based on that skill), and activities for building sight word acquisition. For

this study, during literacy center time, I worked with small groups using the play-based materials

targeting the specific skill that the students needed to improve on. During this time, I was able to

meet with each student at least 3 times each week. One student was working on word

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

25

segmenting, eight students were working on letter sounds, and six students were working on

sight word recognition. Each group was presented with a set of play-based materials. The

student working on segmenting was offered picture cards, a magnetic wand, magnetic chips, and

a picture sorting game. The students working on letter sounds were offered letter sound cards, a

CVC word building game, and a sand timer. The sight word group was offered sight word cards,

a timer, and a Roll-Say-Keep sight word game. Depending on the rotation of centers, I asked

two-three students to my table to play. I would then lay the materials out on the table in front of

them, and explain what the goal was in using them, and left it up to the students to decide how

they wanted to use the materials. As the students worked together to figure out how they wanted

to use the play-based materials for that day, I simply observed and answered questions they had,

and was there to scaffold their learning. The most popular choice throughout the two-week

intervention became using the sand timer and letter sound cards or sight word cards. The

students chose to race to see who could get the most letter sounds, or the most sight words before

the sand timer ran out. Two students asked me to record the number they got on their first turn

so they could try for more on their next turn. Another popular choice was to race to beat the

timer in building CVC words. One group often chose the same Roll-Say-Keep game, but would

vary the rules from taking two cards per roll of the dice, to each person taking a card per roll.

They were in charge of making the rules and utilizing the materials in a way they wanted and

agreed upon. Some days took longer than others to come to an agreement on the activity choice

and rules. However, watching the students discuss and negotiate was incredibly eye opening.

They came up with ways to use the materials I had never thought about, for example, racing the

timer to build CVC words. They were helpful to one another if they did not know a sound or a

word, often another student in the group did know it, and would offer their help.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

26

RESULTS

Play-based learning to acquire specific phonemic awareness and phonics skills took place

over a two-week period of time. Each student engaged in play-based learning activities three

times each week, for a total of 6 times. At the end of the two-week period, each student was re-

assessed using the progress monitoring tool from FastBridge Learning. See Appendix A for the

progress monitoring tools used. The tables below show the baseline score in each area, the score

on the progress monitoring assessment, and the change that happened. In this study, each

student’s score showed positive growth.

Table 1

Word Segmenting

Student

B1

Baseline

0

Progress

Monitoring

9

Progress

Monitoring

+9

Note: Only one child was still working toward mastery segmenting words. This students’

baseline score of 0 was significantly lower than his peers.

Table 2

Letter Sounds

Student

B2

B3

B4

B5

G1

G3

B6

G4

Baseline

8

10

11

14

18

20

21

25

Progress

Monitoring

26

39

32

39

33

37

50

49

Change

+18

+29

+21

+25

+15

+17

+29

+24

Note: Each child working on letter sounds made gains using play-based activities. The average

change from the baseline assessment to the progress monitoring assessment date was an average

of +22.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

27

Table 3

Sight Words

Student

B7

G6

G7

G8

G9

G10

Baseline

9

21

7

6

8

7

Progress

Monitoring

14

32

9

22

21

14

Change

+5

+11

+2

+16

+3

+7

Note: Each child working on sight words made gains using play-based activities. The average

change from the baseline assessment to the progress monitoring assessment date was an average

of +7.

The findings were slightly unexpected, while I did expect growth to happen, most

students’ growth was higher than I anticipated it would be. The data in each area of either

phonemic awareness or phonics skills agrees with the research that I found in favor of using

play-based learning. Guided play-based opportunities serve as an effective way for children to

be engaged in the learning process (Weisberg, et al. 2013, as cited by Cavanaugh et al., 2016).

The results of the study confirm this to be true for the students I was working with this year. The

students were in control of their learning, making choices that were motivating for them to learn

the targeted skills, and appeared to be enjoying their newfound games they created. Play-based

learning had a positive impact on phonemic awareness and phonics skill acquisition for the

students in my kindergarten class.

Conclusion

When I first started to entertain the idea of play-based learning, I knew it was the right

choice developmentally for my students, but it was hard to give up that control in my classroom.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

28

I was also unsure that my students would utilize the materials in a way that was conducive to

learning the skills intended. After completing this study, it has become very clear that they are in

fact capable of using play-based learning materials for building phonemic awareness and phonics

skills. It was helpful for me to be there as a guide if needed, however, after the first couple of

times using the materials, they grew comfortable and confident and quickly took the lead on their

learning.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

29

CHAPTER 5

ACTION PLAN AND PLAN FOR SHARING

Plan for Taking Action

After studying the effects of play-based learning on phonemic awareness and phonics

skills, I plan to continue with this method of instruction as it has proven to be an effective way

for my students to acquire these important early literacy skills. In order to continue with this, I

will continue to look at the data and monitor progress so that I am able to provide my students

with the materials that best suit the skills they are working towards mastering.

I plan to start the school year next year with this strategy during center time, and allow my

students the freedom to make the rules and decisions with the materials to see where it leads

them. I plan to look at the FAST Assessment data, just as I did for this study, to determine the

play-based materials to offer my students. I found it to be beneficial that I am there to guide at

first, to explain the goals in working with the play-based materials, and also to help build their

confidence that their ideas are worth exploring.

Plan for Sharing

I plan on sharing the research, strategies I used, and the data from my action research

study at our next PLC meeting, along with my district administration. My colleagues and I often

discuss the strategies we are using, and question the effectiveness of what is we are doing. Both

kindergarten and first grade has been implementing center style, play-based learning on some

level for the last year. I am excited to share with them the research, and results from the

strategies that my students created. Using this strategy means spending less time on the boxed

curriculum that our district provides, but with the data that I have from this action research study,

I am confident in showing administration that the strategies used are in fact effective in acquiring

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

30

the foundational literacy skills necessary for my students to succeed not only in kindergarten, but

in the grades following.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

31

REFERENCES

Barsness, K. (2017) Are We Doing Kindergarten All Wrong? Empowering Research for

Educators, 1 (1), 3.6. From https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/ere/vol1/iss1/2

Campbell, M. L., Helf, S., & Cooke, N. L. (2008). Effects of adding multisensory components to

a supplemental reading program on the decoding skills of treatment resisters. Education

& Treatment of Children, 31(3), 267-295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798409357580

Cavanaugh, D. M., Clemence, K. J., Teale, M. M., Rule, A. C., & Montgomery, S. E. (2017).

Kindergarten scores, storytelling, executive function, and motivation improved through

literacy-rich guided play. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(6), 831-843.

doi:http://dx.doi.org.pearl.stkate.edu/10.1007/s10643-016-0832-8

Cherry, K. (2020). What Are Piaget's Four Stages of Development? Retrieved October 20, 2020,

from https://www.verywellmind.com/piagets-stages-of-cognitive-development-2795457

Christie, J., & Roskos, K. (2011). The Play-Literacy Nexus and the Importance of Evidence-

Based Techniques in the Classroom. American Journal of Play. 4(2), 204-224.

Clark, K.R. (2018). Learning Theories: Constructivism. Radiologic Technology, 90(2) 180-182.

Danniels E., Pyle A. Defining Play-based Learning. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV,

eds. Pyle A, topic ed.Encyclopedia on Early Childhood

Development [online]. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/play-based-

learning/according-experts/defining-play-based-learning.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

32

Early literacy skills - Early readers - Vocabulary and literacy. (n.d.). Retrieved November 04,

2020, from https://www.renaissance.com/solutions/early-literacy/

Elliott, E. M., & Olliff, C. B. (2008). Developmentally Appropriate Emergent Literacy Activities

for Young Children: Adapting the Early Literacy and Learning Model. Early Childhood

Education Journal, 35(6), 551–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-007-0232-1

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (2015). How to design and evaluate research in

education. McGraw-Hill Education.

FastBridge Learning Online Assessment Tool (2020). Illuminate Education Inc.

https://www.fastbridge.org/

Gozali-Lee, E., & Mueller, D. (2013). A review and analysis conducted for Generation Next-

Wilder Foundation. Retrieved October 20, 2020, from

https://www.wilder.org/sites/default/files/imports/GenerationNext_EarlyLiteracyReport_4-

13.pdf

McClelland, M. M., Acock, A. C., & Morrison, F. J. (2006). The impact of kindergarten

learning-related skills on academic trajectories at the end of elementary school. Early

Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(4), 471–490. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.09.003

Mcleod, S. (2019). Jean Piaget's Theory and Stages of Cognitive Development. Retrieved

December 04, 2020, from https://www.simplypsychology.org/piaget.html

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

33

Miller, E., & Almon, J. (2009). Crisis in the Kindergarten: Why Children Need to Play in

School. College Park, MD: Alliance for Childhood. Retrieved from

www.allianceforchildhood.org

Moore, Katelyn. (2020). The Effects of Play-based Learning on Early Literacy Skills in

Kindergarten. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website:

https://sophia.stkate.edu/maed/ 377.

Play-based learning: Synthesis. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. Pyle A, topic

ed. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. http://www.child-

encyclopedia.com/play-based-learning/synthesis. Updated February 2018. Accessed

October 21, 2020

Pyle, A., & Danniels, E. (2017). A continuum of play-based Learning: the role of the teacher in

play-based pedagogy and the fear of hijacking play. Early Education and Development,

28(3), 274.

Pyle, A., Poliszczuk, D., & Danniels, E. (2018). The Challenges of Promoting Literacy

Integration Within a Play-Based Learning Kindergarten Program: Teacher Perspectives

and Implementation. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 32(2), 219–233.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2017.1416006

Pyle, A., Prioletta, J., & Poliszczuk, D. (2018). The play-literacy interface in full-day

kindergarten classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(1), 117-127.

doi:http://dx.doi.org.pearl.stkate.edu/10.1007/s10643-017-0852-z

Tsao, Y. L. (2008). Using guided play to enhance children’s conversation, creativity, and

competence in literacy. Education, 128(3), 515–520.

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

34

Weisberg, D. S., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2013). Guided play: Where curricular

goals meet a playful pedagogy. Mind, Brain, and Education, 7(2), 104–112.

doi:10.1111/mbe.2013.7.issue-2

Weisberg D.S., Zosh J.M. (2018) How Guided Play Promotes Early Childhood Learning. In:

Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. Pyle A, topic ed. Encyclopedia on Early

Childhood Development [online]. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/play-based-

learning/according-experts/how-guided-play-promotes-early-childhood-learning.

Published February 2018. Accessed October 21, 2020.

Yogman, M., Garner, A., Hutchinson, J., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Michnick Golinkoff, R. (2018). The

Power of Play: A Pediatric Role in Enhancing Development in Young Children. Retrieved

November 20, 2020.

https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/142/3/e20182058.full.pdf?utm_sou

rce=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=teaching_autistic_kids_new_play_s

kills&utm_term=2020-07-16

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

35

Appendix A

Word Segmenting Assessment Form

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

36

Letter Sounds Assessment Form

Running Head: EFFECTS OF PLAY-BASED LEARNING

37

Sight Words Assessment Form